Long Term Care Facility Evacuation Resident Assessment Form for

What is the long term care assessment form for?

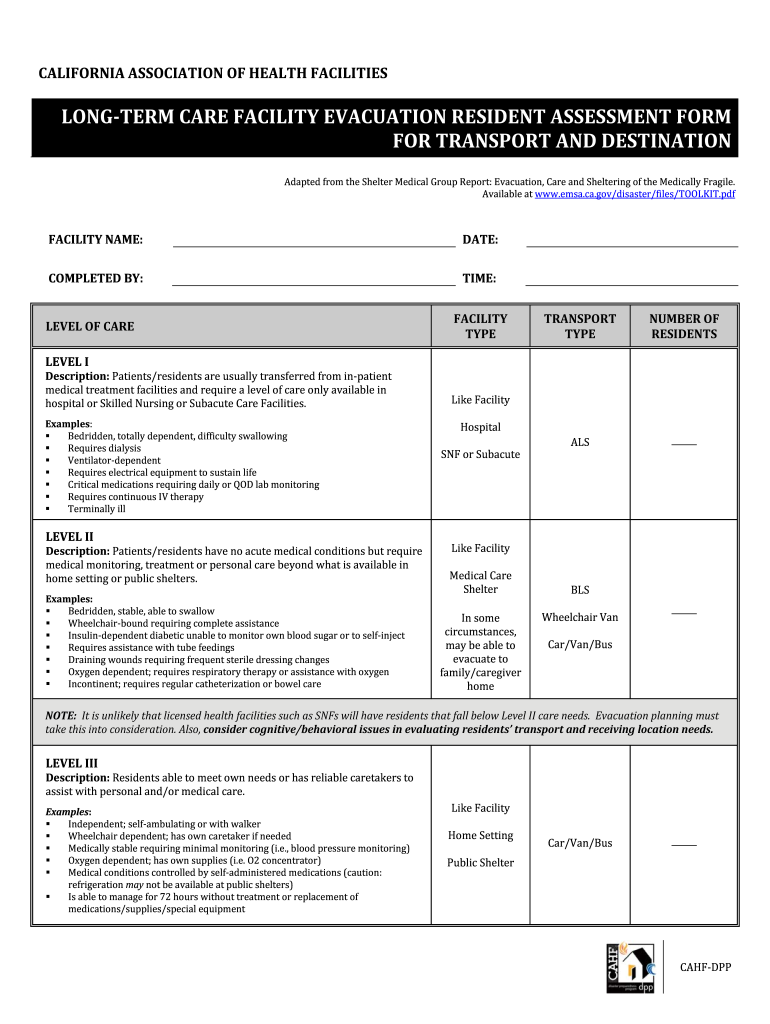

The long term care assessment form is a crucial document used to evaluate the needs and preferences of individuals seeking long-term care services. This form helps healthcare providers gather comprehensive information about a resident's medical history, physical capabilities, and personal preferences. It is designed to ensure that the care provided aligns with the individual's unique requirements and lifestyle choices. By using this form, facilities can create tailored care plans that enhance the quality of life for residents in assisted living or nursing home settings.

How to use the long term care assessment form

Using the long term care assessment form involves several key steps to ensure accurate and effective completion. First, gather all necessary information, including the individual's medical history, current medications, and any specific care needs. Next, fill out the form thoroughly, providing detailed responses to each section. It is essential to involve the individual or their family members in this process to capture their preferences and concerns accurately. Once completed, the form should be reviewed by a healthcare professional to ensure all information is correct and comprehensive before being submitted to the appropriate facility.

Key elements of the long term care assessment form

The long term care assessment form typically includes several key elements that are vital for a thorough evaluation. These elements often encompass:

- Personal Information: Name, date of birth, and contact details.

- Medical History: Previous illnesses, surgeries, and ongoing health conditions.

- Current Medications: A list of all medications being taken, including dosages.

- Physical Abilities: Assessment of mobility, strength, and any assistive devices used.

- Social Preferences: Insights into the individual’s lifestyle, hobbies, and social interactions.

These elements help create a comprehensive profile that guides care planning and service delivery.

Steps to complete the long term care assessment form

Completing the long term care assessment form involves a systematic approach to ensure accuracy and thoroughness. Here are the steps to follow:

- Gather all necessary documents and information related to the individual's health and preferences.

- Begin filling out the form, starting with personal information.

- Carefully document the medical history and current medications.

- Assess and record physical abilities, noting any limitations.

- Include social preferences to provide a holistic view of the individual's needs.

- Review the completed form for accuracy and completeness.

- Submit the form to the relevant healthcare provider or facility.

Legal use of the long term care assessment form

The long term care assessment form must be used in compliance with various legal and regulatory standards. It is essential to ensure that all information is collected and stored in accordance with privacy laws, such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). This ensures that the individual's personal and medical information remains confidential and secure. Additionally, the form must be signed by the individual or their authorized representative to validate the information provided, making it a legally binding document that supports care planning and service delivery.

Examples of using the long term care assessment form

There are several scenarios in which the long term care assessment form is utilized effectively. For instance:

- A nursing home may use the form to evaluate new residents, ensuring their care plans are tailored to their specific needs.

- Assisted living facilities may require the form to assess the suitability of their services for prospective residents.

- Home health care agencies may use the form to determine the level of care required for individuals receiving services at home.

These examples illustrate the form's versatility in various settings, enhancing the quality of care provided to individuals in need.

Quick guide on how to complete long term care facility evacuation resident assessment form for

Explore the simpler method to manage your Long term Care Facility Evacuation Resident Assessment Form For

The traditional methods of finalizing and endorsing documents consume an excessive amount of time in comparison to contemporary document management systems. You would previously look for appropriate forms, print them, fill in all the details, and mail them via postal service. Now, you can obtain, fill out, and sign your Long term Care Facility Evacuation Resident Assessment Form For all within a single web browser tab using airSlate SignNow. Completing your Long term Care Facility Evacuation Resident Assessment Form For has never been easier.

Steps to finalize your Long term Care Facility Evacuation Resident Assessment Form For with airSlate SignNow

- Access the category page you require and locate your state-specific Long term Care Facility Evacuation Resident Assessment Form For. Alternatively, utilize the search bar.

- Verify that the version of the form is accurate by previewing it.

- Click Acquire form and enter editing mode.

- Fill out your document with the necessary information using the editing tools.

- Examine the information added and click the Sign feature to validate your form.

- Select the most suitable method to create your signature: generate it, sketch your sign, or upload an image of it.

- Click COMPLETED to save modifications.

- Download the document to your device or proceed to Sharing options to send it electronically.

Robust online solutions such as airSlate SignNow make completing and submitting your forms easier. Use it to discover how quickly document management and approval tasks are meant to be conducted. You'll save a substantial amount of time.

Create this form in 5 minutes or less

FAQs

-

How do we fix a mental health care system for children without parents having to give up custody to the state for placement in a long-term residential facility?

All mental health problems in children, as far as I am concerned, are because of the parent’s lack of parenting skills in the first place or even grandparents, if they have been allowed the influence, from the child’s birth. Children don’t self-harm because they are happy, they do it due to being either sexually, physically, mentally or emotionally abused by a parent, relative or friend/bully, over a number of years. The younger it started, the more suicidal they will become.Parents will lie and be in total denial, so will any relative. The child needs to be interviewed away from the parent, regardless of age, with a psychologist in the room.Some children are petrified, so they won’t ever speak about their abuse, so nothing can be dealt with, although expressing themselves through drawings can help analyse their behaviour.Any innocent parent, who has played no part in the child’s mental demise will allow this. So, the need for placement in a care facility will be reduced because issues can be easily addressed.When it is clear the child’s home life is having a detrimental effect on his/her well being, only then should the child be offered respite long-term.

-

What are the different ITR forms to be filled out to pay taxes for stock trading (intraday or long-term investing) and mutual funds?

No seperate forms are required. You can fill all your income from all different sources in the different coloumns and arrive at the totalntaxable income, pay tax and file the form online.

-

How long does it take for Facebook to get back to you after you fill out your account form when you got locked out?

Up to 48 hrs.

-

I have a class lesson assessment form that I need to have filled out for 75 lessons. The form will be exactly the same except for the course number. How would you do this?

Another way would be to use the option of getting pre-filled answers with the course numbers entered. A custom URL is created and the form would collect the answers for all of the courses in the same spreadsheet. Not sure if that creates another problem for you, but you could sort OR filter the sheet once all the forms had been submitted. This is what the URL would look like for a Text Box https://docs.google.com/forms/d/1Ia6-paRijdUOn8U2L2H0bF1yujktcqgDsdBJQy2yO30/viewform?entry.14965048=COURSE+NUMBER+75 The nice thing about this is you can just change the part of the URL that Contains "COURSE+NUMBER+75" to a different number...SO for course number 1 it would be https://docs.google.com/forms/d/1Ia6-paRijdUOn8U2L2H0bF1yujktcqgDsdBJQy2yO30/viewform?entry.14965048=COURSE+NUMBER+1This is what the URL would look like for a Text Box radio button, same concept. https://docs.google.com/forms/d/1Ia6-paRijdUOn8U2L2H0bF1yujktcqgDsdBJQy2yO30/viewform?entry.14965048&entry.1934317001=Option+1 OR https://docs.google.com/forms/d/1Ia6-paRijdUOn8U2L2H0bF1yujktcqgDsdBJQy2yO30/viewform?entry.14965048&entry.1934317001=Option+6The Google Doc would look like this Quora pre-filled form I'm not sure if this helps at all or makes too complicated and prone to mistakes.

-

Someone is impersonating my Instagram. How long will it take for the impersonation account to be deleted? Do I get a notification? I filled out the form and sent a photo of myself with my ID, but received no confirmation it was received.

This would be in keeping with the idea of individual freedom, in that, each person should be free to define his own thinking and his own life absent those real actions, not opinions, that are detrimental to another or to society.In keeping with the tradition of American freedom to think independently as noted here with a Thomas Jefferson quote from 1802 in a letter to the Baptist Bishops of Danbury CT. The Bishops were intent on making the Baptist Church the default religion of the new“Believing with you that religion is a matter which lies solely between Man & his God, that he owes account to none other for his faith or his worship, that the legitimate powers of government signNow actions only, & not opinions, I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature should "make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof," thus building a wall of separation between Church & State.”Freedom of religion is a great deal more that deciding what god one may or may not believe in; it is the freedom to think independently, to hold with value those opinions that may differ from others or from government as opposed to a government sponsored and centered belief, which in itself may become intellectually stifling and oppressive to the imaginative mind.Freedom of Religion is also freedom from a religious mandate to believe or to hold one religious belief above all others. The definition of religion is simply the claim that my belief is of “supreme importance” which may also apply to that secular or political ideology and even to that atheistic belief or opinion that gods do not exist. Religious belief is not exclusive to the supernatural, but, rather, inclusive of all opinion.As an Atheist, my Atheism is my opinion of life and living, my religious belief, and I consider it of “supreme Importance” to me, and do I believe that others should think the same, yes, I do. Do I believe that I should make or force others to believe as I do, no.Hopefully there will come a day, in keeping with the thought, the wish and the dream of Martin Luther King, that we are judged not by the god one may or may not belief in, ”—- but by the content of their character.”“I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character.” Martin Luther King, Jr.To respond directly to the question of what religion is best for America and in keeping with the definition of religion as something of supreme importance, I would say that the American Constitution is, by far, the best religion for American

-

What was it like in a Japanese internment camp in America?

If this answer your question: From: Internment of Japanese Americans (Wikipedia)Exclusion, removal, and detentionField laborers of Japanese ancestry stand in front of a Wartime Civil Control Administration site, where they are seeking instruction in regards to their "evacuation".Somewhere between 110,000 and 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry were subject to this mass exclusion program, of whom about two-thirds were U.S. citizens.[3] The remaining one-third were non-citizens subject to internment under the Alien Enemies Act; many of these "resident aliens" had long been inhabitants of the United States, but had been deprived the opportunity to attain citizenship by laws that blocked Asian-born nationals from ever achieving citizenship. Also part of the West Coast removal were 101 children of Japanese descent taken from orphanages and foster homes within the exclusion zone.[66]Internees of Japanese descent were first sent to one of 17 temporary "Civilian Assembly Centers," where most awaited transfer to more permanent relocation centers being constructed by the newly formed War Relocation Authority (WRA). Some of those who did report to the civilian assembly centers were not sent to relocation centers, but were released under the condition that they remain outside the prohibited zone until the military orders were modified or lifted. Almost 120,000[3] Japanese Americans and resident Japanese aliens would eventually be removed from their homes in California, the western halves ofOregon and Washington and southern Arizona as part of the single largest forced relocation in U.S. history.Most of these camps/residences, gardens, and stock areas were placed on Native American reservations, for which the Native Americans were formally compensated. The Native American councils disputed the amounts negotiated in absentia by US government authorities and later sued finding relief and additional compensation for some items of dispute.[67]Under the National Student Council Relocation Program (supported primarily by the American Friends Service Committee), students of college age were permitted to leave the camps to attend institutions willing to accept students of Japanese ancestry. Although the program initially granted leave permits to only a very small number of students, this eventually grew to 2,263 students by December 31, 1943.[68]The baggage of Japanese Americans from the west coast, at a makeshift reception center located at a racetrack.An evacuee with family belongings en route to an "assembly center", Spring 1942Curfew and exclusion[edit]On March 2, 1942, General John DeWitt, commanding general of the Western Defense Command, publicly announced the creation of two military restricted zones.[69] Military Area No. 1 consisted of the southern half of Arizona and the western half of California, Oregon and Washington, as well as all of California south of Los Angeles. Military Area No. 2 covered the rest of those states. DeWitt's proclamation informed Japanese Americans they would be required to leave Military Area 1, but stated that they could remain in the second restricted zone.[70] Removal from Military Area No. 1 initially occurred through "voluntary evacuation."[71] Japanese Americans were free to go anywhere outside of the exclusion zone or inside Area 2, with arrangements and costs of relocation to be borne by the individuals. The policy was short-lived; DeWitt issued another proclamation on March 27 that prohibited Japanese Americans from leaving Area 1.[69] A night-time curfew, also initiated on March 27, 1942, placed further restrictions on the movements and daily lives of Japanese Americans.[citation needed]Eviction from the West Coast began on March 24, 1942 with Civilian Exclusion Order No. 1, which gave the 227 Japanese American residents of Bainbridge Island, Washington six days to prepare for their "evacuation" directly to Manzanar.[72] Colorado governor Ralph Lawrence Carr was the only elected official to publicly denounce the internment of American citizens (an act that cost his reelection, but gained him the gratitude of the Japanese American community, such that a statue of him was erected in the Denver Japantown's Sakura Square[73]). A total of 108 exclusion orders issued by the Western Defense Command over the next five months completed the removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast in August 1942.[74]Conditions in the camps[edit]The quality of life in the camps was heavily influenced by which government entity was responsible for them. INS Camps were regulated by international treaty. The legal difference between interned and relocated had signNow effects on those locked up. INS camps were required to provide food quality and housing at the minimum equal to that experienced by the lowest ranked person in the military. Food in INS camps was of better quality than that of WRA camps.According to a 1943 War Relocation Authority report, internees were housed in "tar paper-covered barracks of simple frame construction without plumbing or cooking facilities of any kind." The spartan facilities met international laws, but still left much to be desired. Many camps were built quickly by civilian contractors during the summer of 1942 based on designs for military barracks, making the buildings poorly equipped for cramped family living.Dust storm at Manzanar War Relocation Center.A baseball game at Manzanar. Picture by Ansel Adams c. 1943.The Heart Mountain War Relocation Center in northwestern Wyoming was a barbed-wire-surrounded enclave with unpartitioned toilets, cots for beds, and a budget of 45 cents daily per capita for food rations.[75] Because most internees were evacuated from their West Coast homes on short notice and not told of their assigned destinations, many failed to pack appropriate clothing for Wyoming winters which often signNowed temperatures below 0 degrees Fahrenheit (−18 degrees Celsius). Many families were forced to simply take the "clothes on their backs."[citation needed]Armed guards were posted at the camps, which were all in remote, desolate areas far from population centers. Internees were typically allowed to stay with their families, and were treated well unless they violated the rules. There are documented instances of guards shooting internees who reportedly attempted to walk outside the fences. One such shooting, that of James Wakasa at Topaz, led to a re-evaluation of the security measures in the camps. Some camp administrations eventually allowed relatively free movement outside the marked boundaries of the camps. Nearly a quarter of the internees left the camps to live and work elsewhere in the United States, outside the exclusion zone. Eventually, some were authorized to return to their hometowns in the exclusion zone under supervision of a sponsoring American family or agency whose loyalty had been assured.[76]The phrase "shikata ga nai" (loosely translated as "it cannot be helped") was commonly used to summarize the interned families' resignation to their helplessness throughout these conditions. This was even noticed by the children, as mentioned in the well-known memoir Farewell to Manzanar.Education in the Camps[edit]This section relies largely or entirely upon a single source. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please help improve this articleby introducing citations to additional sources. (December 2013)Of the 110,000 Japanese interned by the United States government during WWII, 30,000 were children.[77] Most were school age children, and so educational facilities were set up in the camps. However, the camps were never intended to be the long-term entities that they became, and so no real budget or plan was set aside for the new camp educational facilities.[78] Camp schoolhouses were crowded, with insufficient materials, books, notebooks, and desks; the ‘schoolhouses’ themselves were the prison-esque blocks that contained few windows, and in the Southwest, when temperatures rose and the schoolhouse filled, the rooms would be sweltering and unbearable.[78] Class sizes were also immense. At the height of it attendance, the Rohwer Camp of Arkansas signNowed 2,339, to 45 certified teachers.[79] The teacher to student ratio in the camps was an 48:1 in elementary schools and 35:1 for secondary schools, compared to the national average of 28:1.[80][clarification needed] The rhetorical curriculum of the schools was based mostly on the study of “the democratic ideal and to discover its many implications.”.[81] English compositions researched at the Jerome and Rohwer camps in Arkansas focused on these ‘American ideals’, and many of the compositions pertained to the internment camps. Responses were varied, as schoolchildren of the Topaz Camp were patriotic and believed in the war effort, but still could not ignore the fact of their internment.[82][clarification needed]Student Leave to Attend Eastern Colleges[edit]The American Friends Service Committee petitioned Director Milton Eisenhower to place college students in eastern academic institutions. 143 institutions east of the Mississippi opened their doors to college-age youth who had been placed behind barbed wire, many of whom had been enrolled in West Coast schools prior to the exclusion.[83] By September 1942, after the initial roundup of Japanese Americans, 250 students from assembly and relocation centers were back at school. Their tuition, book costs and living expenses were absorbed by the U.S. government. AtEarlham College, President William Dennis helped institute a program that enrolled several dozen Japanese American students in order to spare them from incarceration. While this action was controversial in Richmond, Indiana, it helped strengthen the college's ties to Japan and the Japanese American community.[84] At Oberlin College, about 40 evacuated Nisei students were enrolled. One of them, Kenji Okuda, became student council president.[83]Loyalty questions and segregation[edit]In late 1943, War Relocation Authority officials, working with the War Department and the Office of Naval Intelligence,[85] circulated a question form in an attempt to determine the loyalty of incarcerated Nisei men they hoped to recruit into military service. The "Statement of United States Citizen of Japanese Ancestry" was initially given only to Nisei who were eligible for service (or would have been, but for the 4-C classification imposed on them at the start of the war), but authorities soon revised the questionnaire and required all adults in camp to complete the form. Most of the 28 questions were designed to assess the "Americanness" of the respondent — had they been educated in Japan or the U.S.? were they Buddhist or Christian? did they practice judo or play on a baseball team?[85] The final two questions on the form, which soon came to be known as the "loyalty questionnaire," were more direct: Question 27 asked whether an individual would be willing to serve in the armed forces (or, for women, the Auxiliary Corps) while Question 28 asked them to forswear their allegiance to the Emperor of Japan. Across the camps, persons who answered No to both questions became known as "No Nos."While most camp inmates simply answered "yes" to both questions, several thousand — 17 percent of the total respondents, 20 percent of the Nisei[86] — gave negative or qualified replies out of confusion, fear or anger at the wording and implications of the questionnaire. In regard to Question 27, many worried that expressing a willingness to serve would be equated with volunteering for combat, while others felt insulted at being asked to risk their lives for a country that had imprisoned themselves and their families. An affirmative answer to Question 28 brought up other issues. Some believed that renouncing their loyalty to Japan would be an admission that they had at some point been disloyal to the United States. Many believed they were to be deported to Japan no matter how they answered and feared an explicit disavowal of the Emperor would make that resettlement extremely difficult.On July 15, 1943, Tule Lake, the site with the highest number of "no" responses to the questionnaire, was designated to house the "disloyal" inmates.[86] Over the rest of 1943 and into early 1944, over 12,000 men, women and children were transferred to the maximum security Tule Lake Segregation Center from other camps. When the government passed the Renunciation Act of 1944, a law that made it possible for Nisei and Kibei to renounce their American citizenship, 5,589 internees opted to do so; 5,461 of these were sent to Tule Lake.[87] Of those who renounced their citizenship, 1,327 were repatriated to Japan.[87] Many of these individuals would later face stigmatization in the Japanese American community, during and after the war, for having made that choice, although at the time they were not certain what their futures held were they to remain American, and remain interned.[87]These renunciations of American citizenship have been highly controversial, for a number of reasons. Some apologists for internment have cited the renunciations as evidence that "disloyalty" or anti-Americanism was well represented among the interned peoples, thereby justifying the internment.[88] Many historians have dismissed the latter argument, for its failure to consider that the small number of individuals in question were in the midst of persecution by their own government at the time of the "renunciation":[89][90][T]he renunciations had little to do with "loyalty" or "disloyalty" to the United States, but were instead the result of a series of complex conditions and factors that were beyond the control of those involved. Prior to discarding citizenship, most or all of the renunciants had experienced the following misfortunes: forced removal from homes; loss of jobs; government and public assumption of disloyalty to the land of their birth based on race alone; and incarceration in a "segregation center" for "disloyal" ISSEI or NISEI...[90]Minoru Kiyota, who was among those who renounced his citizenship and swiftly came to regret the decision, has stated that he wanted only "to express my fury toward the government of the United States," for his internment and for the mental and physical duress, as well as the intimidation, he was made to face.[91][M]y renunciation had been an expression of momentary emotional defiance in reaction to years of persecution suffered by myself and other Japanese Americans and, in particular, to the degrading interrogation by the FBI agent at Topaz and being terrorized by the guards and gangs at Tule Lake.[92]Civil rights attorney Wayne M. Collins successfully challenged most of these renunciations as invalid, owing to the conditions of duress and intimidation under which the government obtained them.[91][93] Many of the deportees were Issei (first generation) or Kibei, who often had difficulty with English and often did not understand the questions they were asked.[citation needed] Even among those Issei who had a clear understanding, Question 28 posed an awkward dilemma: Japanese immigrants were denied U.S. citizenship at the time, so when asked to renounce their Japanese citizenship, answering "Yes" would have made them stateless persons.[94]When the government began seeking army volunteers from among the camps, only 6% of military-aged male inmates volunteered to serve in the U.S. Armed Forces.[citation needed] Most of those who refused tempered that refusal with statements of willingness to fight if they were restored their rights as American citizens. 20,000 Japanese American men and many Japanese American women served in the U.S. Army during World War II.[95]The 442nd Regimental Combat Team, which was composed primarily of Japanese Americans, served with uncommon distinction in the European Theatre of World War II. Many of the U.S. soldiers serving in the unit had their families interned at home while they fought abroad.The 442nd Regimental Combat Team, which fought in Europe, was formed from those Japanese Americans who did agree to serve. This unit was the most highly decorated U.S. military unit of its size and duration.[96] In one of the ironies of World War II's concluding stages in Europe, the 442nd's ownNisei segregated field artillery battalion, then on detached service within the U.S. Army in Bavaria, was responsible for liberating at least one of the satellite labor camps of the Nazis' original concentration camp at Dachau on April 29, 1945.[97]Proving their Commitment to the United States[edit]It was not uncommon for the children of Japanese immigrants in the United States to feel an inherited inclination to prove themselves as loyal American citizens. Of the 20,000 Japanese Americans who served in the Army during World War II,[95] “many Japanese-American soldiers had gone to war to fight racism at home” [98] and they were “proving with their blood, their limbs, and their bodies that they were truly American,”.[99] Satoshi Ito, an internment camp survivor, reinforces the idea of the immigrants’ children striving to demonstrate their patriotism to the United States. He notes that his mother would tell him, “‘you’re here in the United States, you need to do well in school, you need to prepare yourself to get a good job when you get out into the larger society’”,[100] and that she would make statements such as “‘don’t be a dumb farmer like me, like us’” [101] to encourage Ito to successfully assimilate into American society. As a result, he worked exceptionally hard to excel in school and later became a professor at the College of William & Mary. His story, along with the countless Japanese Americans willing to risk their lives in war, demonstrate the lengths many in their community went to prove their American patriotism.Other detention camps[edit]As early as 1939, when war broke out in Europe and while armed conflict began to rage in East Asia, the FBI and branches of the Department of Justice and the armed forces began to collect information and surveillance on influential members of the Japanese community in the United States. These data were included in the Custodial Detention index (CDI). Agents in the Department of Justice's Special Defense Unit classified the subjects into three groups: A, B and C, with A being "most dangerous," and C being "possibly dangerous."After the Pearl Harbor attacks, Roosevelt authorized his attorney general to put into motion a plan for the arrest of individuals on the potential enemy alien lists. Armed with a blanket arrest warrant, the FBI seized these men on the eve of December 8, 1941. These men were held in municipal jails and prisons until they were moved to Department of Justice detention camps, separate from those of the Wartime Relocation Authority (WRA). These camps operated under far more stringent conditions and were subject to heightened criminal-style guard, despite the absence of criminal proceedings.Crystal City, Texas, was one such camp where Japanese Americans, German Americans, Italian Americans, and a large number of U.S.-seized, Axis-descended nationals from several Latin-American countries were interned.[65][102]Canadian citizens with Japanese ancestry were also interned by the Canadian government during World War II (see Japanese Canadian internment). Japanese people from various parts of Latin America, including Peru, were brought to the United States for internment or interned in their countries of residence,[102] and there were varied restrictions placed on Japanese Brazilians.[103]Hawaii[edit]There was a strong push from mainland Congressmen (Hawaii was only a U.S. territory at the time, and did not have a voting representative or senator in Congress) to remove and intern all Japanese Americans and Japanese immigrants in Hawaii. 1,200 to 1,800 Japanese nationals and Japanese Americans from Hawaii were interned, either in five camps on the islands or in one of the mainland internment camps. This represented well under two percent of the total Japanese American and Japanese residents in the islands.[104]The vast majority of Japanese Americans and their immigrant parents in Hawaii were not interned because the government had already declaredmartial law in Hawaii and this allowed it to signNowly reduce the supposed risk of espionage and sabotage by residents of Japanese ancestry. Also Japanese Americans comprised over 35% of the territory's population, with about 150,000 inhabitants; detaining so many people would have been enormously challenging in terms of logistics. Also, the whole of Hawaiian society was dependent on their productivity. Lieutenant General Delos C. Emmons, commander of the Hawaii Department, promised the local Japanese American community that they would be treated fairly so long as they remained loyal to the United States, and he succeeded in blocking efforts to relocate them to the outer islands or mainland by pointing out the logistical difficulties.[105] Among the small number interned were a number of community leaders and prominent politicians, including territorial legislators Thomas Sakakihara and Sanji Abe.[106]There were five internment camps in Hawaii, referred to as "Hawaiian Island Detention Camps".[107] One camp was located at Sand Island at the mouth of Honolulu Harbor. This camp was prepared in advance of the war's outbreak. All prisoners held here were "detained under military custody... because of the imposition of martial law throughout the Islands". Another Hawaiian camp was the Honouliuli Internment Camp, near Ewa, on the southwestern shore of Oahu; it was opened in 1943 to replace the Sand Island camp. One was also located on the island of Maui in the town of Haiku.[108] The Kilauea Detention Center on Hawaii (island), and Camp Kalaheo on Kauai.[109] In total, five internment camps operated in the territory of Hawaii.[107][110]Limited Evacuations in Hawaii[edit]Although there were several camps set up along the West Coast of the United States and those of Japanese descent living in the mainland were eventually forced to evacuate, evacuations in Hawaii were very limited. “No serious explanations were offered as to why…the internment of individuals of Japanese descent was necessary on the mainland, but not in Hawaii, where the large Japanese-Hawaiian population went largely unmolested.”[111] One factor may have been that if the people of Japanese descent were interned then the economy of Hawaii would have suffered.[112] Frank, Richard B. Zero Hour on Niihau: World War II 24, no. 2 (July 2009) 54 In 1940, there was a total population of 423,330 ; with 157,905 of the total being people of Japanese descent.[113] The Japanese population was the largest ethnic group on the island during this time. It would mean taking away a large percentage of the work force. This ethnic group had a great impact on the economy of Hawaii. “According to intelligence agents, the Japanese, through a concentration of effort in select industries, had achieved a virtual stranglehold on several key sectors of the economy in Hawaii.”[114] “The Japanese in Hawaii had access to virtually all jobs in the economy, including high-status, high-paying jobs (e.g., professional and managerial jobs).”[115] To imprison such a large of a group from the islands would cripple the Hawaiian economy. The unfounded fear of Japanese Americans turning against the United States was overcome by the fear of economic loss.Japanese Latin Americans[edit]During World War II, over 2,200 Japanese from Latin America were held in internment camps run by the Immigration and Naturalization Service, part of the Department of Justice. Beginning in 1942, Latin Americans of Japanese ancestry were rounded up and transported to American internment camps run by the INS and the U.S. Justice Department.[18][116][117][118] The majority of these internees, approximately 1,800, came from Peru. An additional 250 were from Panama, and Bolivia, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Ecuador, El Salvador, Mexico, Nicaragua, and Venezuela also deported much of their, considerably smaller, populations of Japanese immigrants.[119]The first group of Japanese Latin Americans arrived in San Francisco on April 20, 1942, on board the Etolin along with 360 ethnic Germans and 14 ethnic Italians from Peru, Ecuador and Colombia.[120] The 151 men — ten from Ecuador, the rest from Peru — who had volunteered for deportation believing they were to be repatriated to Japan, were denied visas by U.S. Immigration authorities and then detained on the grounds they had attempted to enter the country illegally, without a visa or passport.[120] Subsequent transports brought additional "volunteers," including the wives and children of men who had been deported earlier. A total of 2,264 Japanese Latin Americans, about two-thirds of them from Peru, were interned in facilities on the U.S. mainland during the war.[18][119][121]The United States originally intended to trade these Latin American internees as part of a hostage exchange program with Japan and other Axis nations.[122] A thorough examination of the documents shows at least one trade occurred.[116] Over 1,300 persons of Japanese ancestry were exchanged for a like number of non-official Americans in October 1943, at the port of Marmagao, India. Over half were Latin American Japanese (the rest being ethnic Germans and Italians) and of that number one-third were Japanese Peruvians.On September 2, 1943, the Swedish ship MS Gripsholm departed the U.S. with just over 1,300 Japanese nationals (including nearly a hundred from Canada and Mexico) en route for the exchange location, Marmagao, the main port of the Portuguese colony of Goa on the west coast of India.[123] [124] After two more stops in South America to take on additional Japanese nationals, the passenger manifest signNowed 1,340.[116] Of that number, Latin American Japanese numbered 55 percent of the Gripsholm's travelers, 30 percent of whom were Japanese Peruvian.[116]Arriving in Marmagao on October 16, 1943, the Gripsholm's passengers disembarked and then boarded the Japanese ship Teia Maru. In return, "non-official" Americans (secretaries, butlers, cooks, embassy staff workers, etc.) previously held by the Japanese Army boarded the Gripsholm while the Teia Maru headed for Tokyo.[116] Because this exchange was done with those of Japanese ancestry officially described as "volunteering" to return to Japan, no legal challenges were encountered. The U.S. Department of State was pleased with the first trade and immediately began to arrange a second exchange of non-officials for February 1944. This exchange would involve 1,500 non-volunteer Japanese who were to be exchanged for 1,500 Americans,[116] but the momentum of the war had shifted to the U.S. (particularly in Pacific Naval activity) and future trading plans stalled. Further slowing the program were legal and political "turf" battles between the State Department, the Roosevelt administration, and the DOJ, whose officials were not convinced of the legality of the program.The completed October 1943 trade took place at the height of the Enemy Alien Deportation Program. Japanese Peruvians were still being "rounded up" for shipment to the U.S. in previously unseen numbers. Despite logistical challenges facing the floundering prisoner exchange program, deportation plans were moving ahead. This is partly explained by an early-in-the-war revelation of the overall goal for Latin Americans of Japanese ancestry under the Enemy Alien Deportation Program. The goal: that the hemisphere was to be free of Japanese. Secretary of State Cordell Hull wrote an agreeing President Roosevelt, "[that the US must] continue our efforts to remove all the Japanese from these American Republics for internment in the United States."[116][125]The extreme animosity of "native" Peruvians toward their Japanese citizens and expatriates cannot be overstated, and Peru's government refused to accept the post-war return of Japanese Peruvians they had gladly handed over to the U.S. years earlier. Although a small number asserting special circumstances, such as marriage to a non-Japanese Peruvian,[18] did return, the majority were trapped. Their home country refused to take them back (a political stance Peru would maintain until 1950[119]) and the post-war U.S. DOS, anxious to rid itself of them, began expatriating them to Japan. ACLU lawyer Wayne Collins filed injunctions on behalf of the remaining internees,[102][126] helping them obtain "parole" relocation to the labor-starved Seabrook Farms in New Jersey,[127] and started a legal battle journey that would not be resolved until 1953, when, after working as undocumented immigrants for almost ten years, those remaining in the U.S. were finally offered citizenship.[116][119]Internment ends[edit]On December 18, 1944, the Supreme Court of the United States clarified the legality of the exclusion process under Order 9066 by handing down two decisions. Korematsu v. United States, a 6–3 decision, stated that the exclusion process in general was constitutional. Ex parte Endounanimously declared that loyal citizens of the United States, regardless of cultural descent, could not be detained without cause.On January 2, 1945, the exclusion order was rescinded entirely. The internees then began to leave the camps to rebuild their lives at home, although the relocation camps remained open for residents who were not ready to make the move back. The freed internees were given $25 and a train ticket to their former homes. While the majority returned to their former lives, some of the Japanese Americans emigrated to Japan.[128]The last internment camp was not closed until 1946;[129] Japanese taken by the U.S. from Peru that were still being held in the camp in Santa Fe took legal action in April 1946 in an attempt to avoid deportation to Japan.[130]One of the WRA camps, Manzanar, was designated a National Historic Site in 1992 to "provide for the protection and interpretation of historic, cultural, and natural resources associated with the relocation of Japanese Americans during World War II" (Public Law 102-248). In 2001, the site of the Minidoka War Relocation Center in Idaho was designated the Minidoka National Historic Site.Hardship and material loss[edit]Graveyard at Granada Relocation Center, in Amache, Colorado.A monument at Manzanar, "to console the souls of the dead."Many internees lost irreplaceable personal property due to the restrictions on what could be taken into the camps. These losses were compounded by theft and destruction of items placed in governmental storage. A number of persons died or suffered for lack of medical care, and several were killed by sentries; James Wakasa, for instance, was killed at Topaz War Relocation Center, near the perimeter wire. Nikkei were prohibited from leaving the Military Zones during the last few weeks before internment, and only able to leave the camps by permission of the camp administrators.Psychological injury was observed by Dillon S. Myer, director of the WRA camps. In June 1945, Myer described how the Japanese Americans had grown increasingly depressed, and overcome with feelings of helplessness and personal insecurity.[131] Author Betty Furuta explains that the Japanese usedgaman, loosely meaning "perseverance", to overcome hardships which was mistaken by non-Japanese as being introverted and lacking initiative.[132]Some Japanese American farmers were able to find families willing to tend their farms for the duration of their internment. In other cases Japanese American farmers had to sell their property in a matter of days, usually at great financial loss. In these cases, the land speculators who bought the land made huge profits. California's Alien Land Laws of the 1910s, which prohibited most non-citizens from owning property in that state, contributed to Japanese American property losses. Because they were barred from owning land, many older Japanese American farmers were tenant farmers and therefore lost their rights to those farm lands.To compensate former internees for their property losses, the US Congress, on July 2, 1948, passed the "American Japanese Claims Act," allowing Japanese Americans to apply for compensation for property losses which occurred as "a reasonable and natural consequence of the evacuation or exclusion." By the time the Act was passed, the IRS had already destroyed most of the 1939–42 tax records of the internees, and, due to the time pressure and the strict limits on how much they could take to the assembly centers and then the internment camps, few of the internees themselves had been able to preserve detailed tax and financial records during the evacuation process. Thus, it was extremely difficult for claimants to establish that their claims were valid. Under the Act, Japanese American families filed 26,568 claims totaling $148 million in requests; about $37 million was approved and disbursed.[133]

Create this form in 5 minutes!

How to create an eSignature for the long term care facility evacuation resident assessment form for

How to make an eSignature for the Long Term Care Facility Evacuation Resident Assessment Form For online

How to make an eSignature for the Long Term Care Facility Evacuation Resident Assessment Form For in Google Chrome

How to generate an electronic signature for signing the Long Term Care Facility Evacuation Resident Assessment Form For in Gmail

How to generate an electronic signature for the Long Term Care Facility Evacuation Resident Assessment Form For right from your smart phone

How to generate an eSignature for the Long Term Care Facility Evacuation Resident Assessment Form For on iOS devices

How to generate an electronic signature for the Long Term Care Facility Evacuation Resident Assessment Form For on Android OS

People also ask

-

What is an assisted living assessment checklist?

An assisted living assessment checklist is a comprehensive tool that helps evaluate the needs of individuals seeking assisted living services. It covers various aspects such as medical history, daily living activities, and personal preferences. Utilizing this checklist can streamline the assessment process for both families and care providers.

-

How can the assisted living assessment checklist benefit my organization?

The assisted living assessment checklist helps your organization systematically evaluate potential residents’ needs. By using this checklist, you ensure that all critical areas are covered, leading to more informed decisions and personalized care plans. This ultimately enhances service quality and resident satisfaction.

-

Is the assisted living assessment checklist customizable?

Yes, the assisted living assessment checklist can be tailored to meet the specific requirements of your organization. This customization allows you to align questions and criteria with your care philosophy and services offered. Personalization helps create a more accurate and relevant assessment for each individual.

-

What features does airSlate SignNow offer for the assisted living assessment checklist?

airSlate SignNow provides several features that enhance the use of the assisted living assessment checklist, including electronic signatures, document templates, and secure cloud storage. These features streamline the documentation process, allowing for faster and more efficient assessments. Additionally, real-time collaboration ensures that all team members can contribute to the assessment seamlessly.

-

How does pricing work for using the assisted living assessment checklist in airSlate SignNow?

Pricing for using the assisted living assessment checklist with airSlate SignNow is subscription-based and varies depending on the features you choose. There are different plans available that cater to different organizational needs, allowing you to select the most cost-effective solution. It's advisable to check the airSlate SignNow pricing page for the most updated information.

-

Can the assisted living assessment checklist integrate with other tools?

Absolutely, the assisted living assessment checklist in airSlate SignNow can integrate seamlessly with various other tools and applications through APIs. This integration allows you to pull in pertinent data and enhance the overall efficiency of your operations. You can connect with popular management systems and other platforms to streamline your workflow.

-

How secure is the information collected through the assisted living assessment checklist?

Security is a top priority for airSlate SignNow, and information collected through the assisted living assessment checklist is protected with robust encryption and compliance protocols. This ensures that sensitive personal data remains confidential and secure. Regular security audits and monitoring help uphold these high standards.

Get more for Long term Care Facility Evacuation Resident Assessment Form For

- Note first will is for husband form

- You consult an attorney form

- When uninformed persons take title to real estate as

- Field 85 form

- Funeral expense information

- With the terms of the will and laws of the state of washington in reference to the procedures and form

- Our domestic partnership was registered with the state of form

- Make a parenting plan packet washingtonlawhelporg form

Find out other Long term Care Facility Evacuation Resident Assessment Form For

- eSign New York Construction Lease Agreement Online

- Help Me With eSign North Carolina Construction LLC Operating Agreement

- eSign Education Presentation Montana Easy

- How To eSign Missouri Education Permission Slip

- How To eSign New Mexico Education Promissory Note Template

- eSign New Mexico Education Affidavit Of Heirship Online

- eSign California Finance & Tax Accounting IOU Free

- How To eSign North Dakota Education Rental Application

- How To eSign South Dakota Construction Promissory Note Template

- eSign Education Word Oregon Secure

- How Do I eSign Hawaii Finance & Tax Accounting NDA

- eSign Georgia Finance & Tax Accounting POA Fast

- eSign Georgia Finance & Tax Accounting POA Simple

- How To eSign Oregon Education LLC Operating Agreement

- eSign Illinois Finance & Tax Accounting Resignation Letter Now

- eSign Texas Construction POA Mobile

- eSign Kansas Finance & Tax Accounting Stock Certificate Now

- eSign Tennessee Education Warranty Deed Online

- eSign Tennessee Education Warranty Deed Now

- eSign Texas Education LLC Operating Agreement Fast