Florida State Fire Marshal Dfs K3 1973 Fillable Form

What is the Florida State Fire Marshal DFS K3 1973 Fillable Form

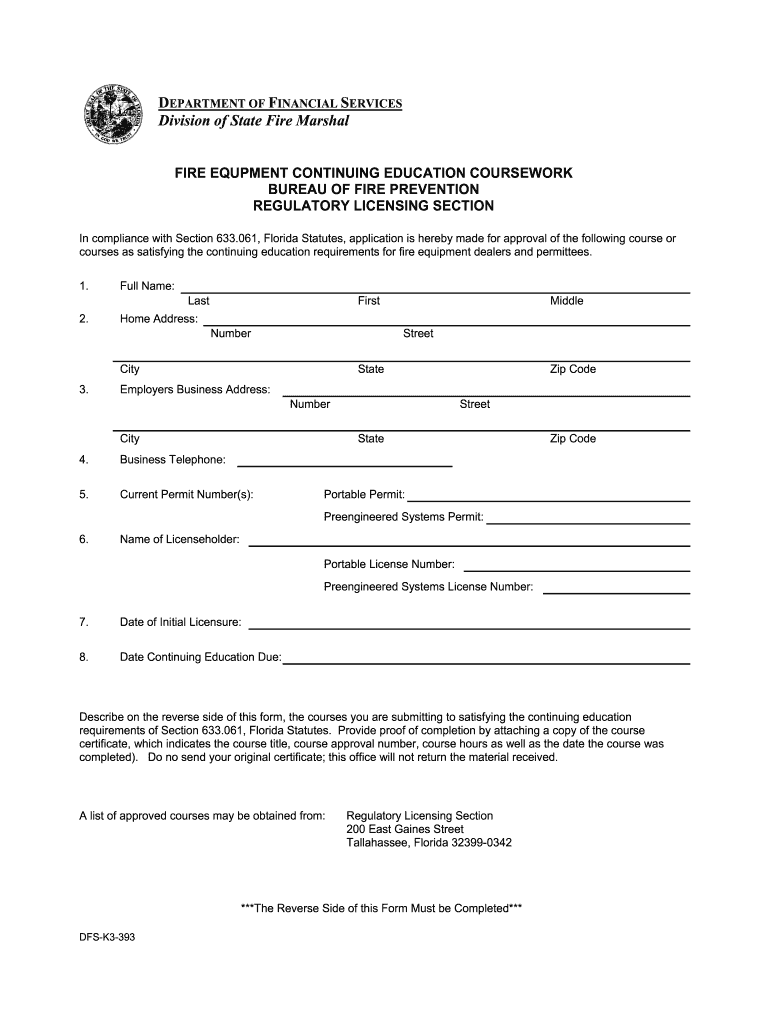

The Florida State Fire Marshal DFS K3 1973 Fillable Form is a crucial document used for reporting fire-related incidents and ensuring compliance with state regulations. This form is designed to capture essential information regarding fire safety inspections, equipment, and training. It serves as a record for fire departments and other entities involved in fire safety and prevention efforts across Florida.

How to use the Florida State Fire Marshal DFS K3 1973 Fillable Form

Using the DFS K3 1973 Fillable Form involves several straightforward steps. First, download the form from a reliable source. Next, fill in the required fields, including details about the fire incident, equipment involved, and any relevant educational coursework completed. Ensure all information is accurate to avoid delays in processing. Once completed, the form can be submitted electronically or printed for physical submission, depending on the requirements of the local fire authority.

Steps to complete the Florida State Fire Marshal DFS K3 1973 Fillable Form

Completing the DFS K3 1973 Fillable Form requires attention to detail. Follow these steps:

- Download the form from an official source.

- Open the form in a compatible PDF reader that allows filling.

- Provide your contact information and the details of the incident.

- Include information about any fire education coursework relevant to the incident.

- Review the completed form for accuracy.

- Submit the form as instructed, either electronically or via mail.

Legal use of the Florida State Fire Marshal DFS K3 1973 Fillable Form

The legal use of the DFS K3 1973 Fillable Form is governed by state regulations regarding fire safety and reporting. This form must be filled out accurately to ensure compliance with the Florida Fire Prevention Code. Proper use of the form helps maintain records that can be critical in investigations, insurance claims, and compliance audits. Failure to use the form correctly may result in penalties or legal repercussions.

Key elements of the Florida State Fire Marshal DFS K3 1973 Fillable Form

Key elements of the DFS K3 1973 Fillable Form include:

- Incident details, such as date, time, and location.

- Information about the fire department responding to the incident.

- Details of any fire safety equipment involved.

- Documentation of fire education coursework completed by personnel.

State-specific rules for the Florida State Fire Marshal DFS K3 1973 Fillable Form

Florida has specific rules governing the use of the DFS K3 1973 Fillable Form. These rules include requirements for timely submission of the form after an incident, as well as guidelines on the types of information that must be reported. It is essential for users to familiarize themselves with these regulations to ensure compliance and avoid potential penalties.

Quick guide on how to complete division of state fire marshal

Manage Florida State Fire Marshal Dfs K3 1973 Fillable Form effortlessly on any device

Digital document management has become a trend among businesses and individuals. It offers an ideal eco-friendly substitute for traditional printed and signed papers, allowing you to obtain the proper form and securely store it online. airSlate SignNow equips you with all the tools necessary to create, edit, and eSign your documents swiftly without delays. Handle Florida State Fire Marshal Dfs K3 1973 Fillable Form on any platform using airSlate SignNow's Android or iOS applications and enhance any document-based task today.

The simplest method to modify and eSign Florida State Fire Marshal Dfs K3 1973 Fillable Form with ease

- Locate Florida State Fire Marshal Dfs K3 1973 Fillable Form and click Get Form to begin.

- Utilize the tools we provide to fill in your document.

- Emphasize signNow sections of your documents or redact sensitive information with tools that airSlate SignNow offers specifically for that purpose.

- Create your signature using the Sign tool, which takes seconds and carries the same legal authority as a conventional wet ink signature.

- Verify the details and click the Done button to save your changes.

- Choose how you want to send your form, via email, text message (SMS), invite link, or download it to your computer.

Eliminate concerns about lost or overlooked documents, tedious form searches, or mistakes that require printing new copies. airSlate SignNow meets your document management needs in a few clicks from a device of your choice. Modify and eSign Florida State Fire Marshal Dfs K3 1973 Fillable Form and guarantee excellent communication at any stage of your form preparation process with airSlate SignNow.

Create this form in 5 minutes or less

FAQs

-

How to decide my bank name city and state if filling out a form, if the bank is a national bank?

Somewhere on that form should be a blank for routing number and account number. Those are available from your check and/or your bank statements. If you can't find them, call the bank and ask or go by their office for help with the form. As long as those numbers are entered correctly, any error you make in spelling, location or naming should not influence the eventual deposit into your proper account.

-

What's the reasoning behind the naming of military units, for instance, there's the 82nd Airborne Division, what has happened to the other 81 divisions?

Tl;dr — United States divisions were numbered semi-sequentially, which meant that the unit known as the 82nd Airborne (originally the 82nd Infantry) got the 82nd “slot.” However, due to the numbering system, which set aside blocks of numbers for different divisional origins (1–25 for Regular Army, for instance), the 82nd Infantry didn’t mean that there were 82 other divisions behind it. It belonged to the block of numbered divisions that were manned by draftees, which started with the 76th Infantry Division and worked its way upward sequentially (76th, 77th, and so on).The idea and reasoning of divisional numbering itself came out of French military theorists who, a) proposed a new unit organization above the then-standard regimental or brigade level, and b) began to turn away from the traditional method of naming units based on the commanding officer, a discussion that was simultaneously happening in Britain regarding British regimental precedence. Some experiments were done with the new unit in the last half of the 18th century, but it wasn’t systematic. It took until the French Revolution for the division to be applied systematically, at first within the French Revolutionary Army, and then later by Europe as a whole. As France had done away with the traditional regiments of the ancien regime, they began to simply number all of their units—including divisions. As such, when divisions were adopted by other nations, they too were numbered.In the United States, divisions tended to be ad-hoc, secondary organizations organized as needed, since the U.S. Army was fairly small. During the Civil War, the regiment remained the basic unit of the army, and the corps was the focus of operational command—hence, divisions existed only as an intermediate unit between the regiment (or brigade) and division, and didn’t tend to have unique numbers, but were instead simply the 1st Division of I Corps, 1st Division of II Corps, and so on. It took until WWI for the U.S. Army to shift its basic unit to the division, whereupon permanent divisions were numbered and established according to the sequential block system mentioned in the first paragraph. In subsequent wars and eras of peacetime, various divisions were deactivated, reactivated, turned into brigades, and merged, leaving only a few divisions with large gaps between them.The simple answer, as others have said, is that the gaps represent deactivated divisions—though it’s a bit more complicated than that. In this case, they’re a little bit like a baseball player’s number—if a player retires, people don’t automatically move up or down a number, it just remains inactive until someone else is assigned it. Just like with baseball jersey numbers, some numbers are inexplicably never assigned, and others are “retired,” and unlikely to be used again.That said, I’ll go a little bit into just why divisions are numbered and how it came to be that we refer to divisions by a number rather than some other form, especially when, in previous eras, it was far more common to name a military organization by region or commander.Until about the 18th century, the primary unit of command was a regiment. Many armies also used brigades, which, depending upon the army, could be combined arms units (say, consisting of an infantry regiment, artillery battery, and some cavalry), or they could just be a small cluster of regiments from the same branch (say, two or three regiments).As armies grew larger and as states began to field larger forces in increasingly intense wars, this system began to break down. A general can effectively command, say, ten or twenty regiments or just so many brigades, but once field armies begin consisting of, say, sixty or even seventy regiments, that’s just too much for a single general to keep track of. The brigade system helped, but not by enough.Enter Marshal Maurice de Saxe.De Saxe saw the ballooning of European armies first hand. Rocroi in 1643 had only some 20,000 men on each side and was a major battle. The Battle of Malplaquet in 1709, just fifty years later and which De Saxe participated in as a young man, involved 86,000 Allies and 75,000 French troops, with a little under 200 guns.He was aware that the increasing size of the French Army had a number of drawbacks. In the past, it was relatively simple to get the number of officers you needed since, of course, you didn’t need quite as many. As the number of regiments grew, you had to increasingly scrape the bottom of the barrel for officers and, often, a good officer’s influence extended only to his own regiment. In addition, regiments varied wildly in quality and veterancy to the point that (to Saxe’s dismay) only a relatively small number of regiments were really useful—and those, predictably, got the most use. He was especially against grenadier regiments, which he saw as sucking up all the good soldiers and leaving the line regiments to get the dregs.De Saxe’s response to that is something he called a legion and which we today would call a division. It was to be a combined arms formation based on the legions of Rome, each consisting of four regiments, with each regiment consisting of four centuries. Each century, in turn, would be accompanied by a half-century of light-armed infantry and a half-century of horse. Each company would also include an amusette, a light field cannon of De Saxe’s own design. This higher level of command would allow good soldiers to rise up to administer and command several regiments rather than just a single regiment, spreading out some of their expertise and ability and allowing their talents to make a bigger impact on the field.Importantly for Saxe, these legions would be formed around cadres of veteran soldiers dispersed around the formation. Unlike in the previous system, where one regiment might be full of veterans and another might be entirely filled with new recruits, Saxe wanted to distribute those veterans evenly between the regiments in his legion. In peacetime, the legion would consist of only these veterans, leaving the legion at reduced strength. During times of war, however, the legion would take on new recruits who would serve alongside these veterans, with the veterans acting as teachers and “corset stiffeners” for the recruits. They would also provide a ready source for NCOs and even officers.More pertinent to the question, De Saxe also advises against the standard naming system of regiments in his day. Regiments in the first half of the 18th century (and before) were often known not by a number, but rather by the name of their colonel, especially if that colonel had a hand in raising and outfitting that regiment. De Saxe knew that soldiers were less likely to be attached to a unit that was simply known by the name of its colonel—what if they hated their colonel?—than to a more abstract form, whether that be a geographical entity or simply to a number. De Saxe, therefore, preferred his regiments and legions to be known by a number—both of which were to be affixed to the soldier’s uniform—rather than the name of their commander.You can read De Saxe’s thoughts on the “legion” form of organization here, in his book Mes Reveres, pp. 33–57.In a British context, a similar matter came to the fore. Regiments in those days had a confusing system of rank and precedence: a new regiment was less prestigious than an old one. This rank and precedence influenced the order of battle, with the most prestigious regiments at the right of the line. The traditional system often led to arguments—was, say, an Irish regiment raised in 1653 higher ranked than an English regiment raised in 1655?—and that led to the creation of a numbering system that settled questions of rank.In response, a formal numbering system was established within the Royal Warrant of 1st July 1751, which standardized each regiment’s colors and precedence. Each regiment was numbered according to when it was raised and came within the system: each English regiment was numbered according to the date when it was raised, while Irish, Scottish, or foreign regiments were numbered from when they arrived in England. The Earl of Bath’s Regiment became the 10th North Lincoln Regiment of Foot, since they were the 10th regiment in precedence and recruited from the North Lincoln (or Lincolnshire) region. So the move towards numbering was occurring in places other than France, even if French officers were the ones to begin talking about organizing those regiments into divisions.De Saxe, however, died early and didn’t have an opportunity to create his legions. During the Seven Years War, the Duke de Broglie conducted a number of successful experiments using De Saxe’s regimental system, but it was unsystematic and rather ad-hoc.It took until the French Revolution for the division to catch on systematically.The foundation of the French Army had been all but destroyed during the revolution. Experienced officers, who were often noblemen, tended to leave the army (or join Royalist forces). The French Revolutionary Government, meanwhile, wanted to tear down the aristocratic regimental system—eventually, they were to (briefly) retire even the word regiment and replace it with the term “demi-brigade.” The government viewed the ongoing war as a people’s war and, accordingly, created massive armies of fresh, often untrained, recruits.Predictably, the French Revolutionary Army did poorly against the professional armies of the other European nations. As defeats mounted, morale fell, which in turn led to a manpower crisis in the French Revolutionary Army—which, basically, only had numbers going for it.Enter Lazare Carnot.The son of a judge, Carnot was a mathematician and military engineer who entered politics during the Revolution and made his first mark in his push for public education and education reform. Eventually, he was elected to the Committee for Public Safety—which oversaw the ongoing war.Ever the reformer, Carnot began rebuilding the French Army. Educated in a military academy, Carnot turned toward the works of De Saxe and the experiments of de Broglie. Carnot believed in the idea of a People’s War, but recognized that recruitment numbers were flagging. In response, he introduced the levee en masse—he introduced conscription.Like De Saxe, he saw that some regiments were full of veterans, while others—the masses of new revolutionary brigades—were filled with barely-trained recruits. And, like De Saxe, his solution was to separate out the veterans and to embed them within these new brigades to teach and guide these recruits on the art of war.Most importantly, he embraced De Saxe’s general idea of the division. The mass forces of the Revolutionary Army were difficult to control and often unwieldy—the entire theory behind the Revolutionary Army was, after all, numbers. Carnot solved this by creating the first systematic divisions: demi-brigades (regiments) would be combined into brigades, and brigades would be combined into divisions. Later, under Napoleon, divisions would be combined into corps.This solved a great deal of the command and control problems within the Revolutionary Army. Suddenly, you had an intermediate level of control between the overall general and the brigade commanders. Those division commanders could take the initiative with their substantial forces while also remaining maneuverable and easy to control. Carnot’s embrace of the idea of the division meant that the Revolutionary Army became, paradoxically, an army of both mass and maneuver—the field army was large, but it was divided up into manageable segments that allowed it to move faster and more decisively than their enemies, who were still commanding at regimental or brigade level. Moving rapidly in column formation—which was easier to train and easier to learn than a line formation—the French forces quickly assumed their positions and then were able to rely on shock and weight of numbers to defeat their opponents.French infantry at the Battle of Eylau. The infantry line formation is on the left, and was favored for veteran troops because of greater frontage. The infantry column formation is on the right, favored for greener troops because it was easier to train and more maneuverable, though lesser frontage meant columns often relied on shock rather than fire.As for names, while the French regiments used a precedence system similar to the British, the idea of naming regiments entirely based on their seniority never caught on. During the Seven Years War, for instance, regiments continued to be named after their colonels or the region in which they were (supposedly) raised.The French Revolutionary Government, however, was both anti-aristocratic and heavily centralizing. That meant that the old system of regiments—as well as naming regiments after their commanders—was retired as a remnant of the ancien regime. The French Revolutionary Government also didn’t like the idea that units were named after regions of France: these were forces raised by and for the nation. In addition, the massive expansion of the Army all but precluded specific names.The Revolutionary Government, therefore, simply numbered these new units. While there were arguments in De Saxe and later on for the principle of numbering—after all, the Roman legions were numbered—chances are that this was mostly an administrative convenience. And, as in the old system, these numbers reflected seniority: just as the Earl of Bath’s Regiment became the 10th Regiment of Foot because it was the 10th in seniority, the (say) 15th Demi-Brigade was the 15th Demi-Brigade raised.Artist’s depiction of a soldier of the French Revolutionary Army, bearing the banner of the 30th Demi-Brigade.In any case, just as the demi-brigades and brigades of the new Revolutionary Army were numbered, so were the divisions.Napoleon, as was often the case, eventually refined the divisional system as we know it today, especially after he began grouping divisions into corps. Corps were another idea discussed during the ancien regime but never really implemented, as well as the concept of the battalion carre, which featured four corps moving in a mutually-supporting diamond formation that was able to deftly pivot in any direction.For instance, Napoleon’s Grande Armee entered Russia with 17 corps, including the Imperial Guard. One of those, II Corps, consisted of three infantry divisions and assorted regiments of cavalry. These included the 6th Division, the 8th Division, and the 9th Division. In, say, the 6th Division, you had the 26th Light Infantry Regiment, the 56th Line Infantry Regiment, the 19th Line Infantry Regiment, the 128th Line Infantry Regiment, and the 3rd Portuguese Regiment, along with cavalry. If the regiment in question had two battalions, it was paired with another two-battalion regiment to create a brigade—if, on the other hand, the brigade was double-strength (four battalions), the brigade and regiment were coterminous.All this represented a gradual refinement and increasing standardization of the division from the Revolutionary Days.As it indeed became more defined and successful against the existing armies in Europe, other European nations began adopting the divisional organization.Wellington, for instance, created the first British divisions in 1809 for the Peninsula campaign: the 1st Infantry Division under General Hope, for example, or the 3rd Infantry Division under Pakenham. As early as 1797, Austrian divisions (though about half the size of the French) appear as formations, such as the one commanded at Rivoli by Peter Quasdanovich. Russian divisions appear as early as Suvorov’s invasion of Italy. And, just as divisions on the French model became standard, so did corps, although generally the French utilized both formations more effectively.The United States, meanwhile, was relatively separate from developments in the Napoleonic Wars. It did, however, have what could be argued was a “division-sized” unit: the Legion of the United States. As with De Saxe’s ideas, the Legion was organized into four “sub-legions” (effectively brigades), which were combined arms combat teams with their own cavalry, infantry, and artillery. They were meant to operate on their own in the western wilderness, fighting against Native American tribes.Soldiers of the Legion of the United States. The soldier on the right wears the iconic bearskin “roundtop” hat of the legion.Such an organization was not to last, however, and by 1800, the Legion was disbanded and the sub-legions converted to standard infantry regiments—the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th Infantry Regiments, after the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th Sub-Legions. The United States, at the time, maintained a fairly small army, and its numbers were such that no permanent division-level commands were necessary. In large engagements, such as battles during the War of 1812, brigades and regiments were often grouped together as needed, but had little to no permanent basis. During the Civil War, the temporary regiments raised by the states were similarly grouped into divisions as needed, but the basic, permanent unit remained the regiment. Divisions then were merely subunits of corps—so you’d have the 1st Division of II Corps, but also the 1st Division of I Corps. In this case, the division was merely an intermediary between the primary tactical unit (the regiment) and the primary operational unit (the corps), and served to streamline command rather than stand as a permanent, independent organization.It took until 1917 for the United States to formally order its regiments into standing divisions. This represented a shift of the basic unit from the regiment to the division—a shift that most European armies (save perhaps the British) had undergone many years before.The First Expeditionary Division—later the 1st Infantry Division—was created in May and shipped off to France. The 2nd Infantry Division was created in October and organized in France. The 3rd Infantry Division was created in November. The mobilization went up to, as in the question, the 82nd Airborne Division (at that time, simply the 82nd Infantry Division).U.S. infantry uniforms during WWI—the 82nd Infantry Division’s uniform is in the middle, with the red and blue patch. From right to left: the 42nd, 1st, 82nd, 77th divisions, a member of the U.S. tank corps, and finally the 91st Infantry DivisionNow, this would suggest that, for the 82nd Airborne, there were 81 divisions that preceded it—which is on the right track, but not quite true. There were still some gaps—for instance, there’s no 21st Division, and the list of US divisions seems to skip between 20th and 26th.The reason for that is that certain numbers were reserved for certain parts of the Army. The Regular Army, for example, had divisions numbered from 1 to 25—but there were only 20 divisions in the Regular Army. The next were National Guard divisions, numbered 26 to 49—those numbers start sequentially at 26 and go up to 42. The next regiments pick up at 76, which is where the drafted divisions begin—i.e., divisions filled by American conscripts. This includes the 82nd. The number tells you that the 82nd got its start as a military unit manned by draftees. There is, as you might have noted, a big gap between 49 and 76—I’m not quite sure what they were meant for (I’ve heard they were meant for cavalry divisions the U.S. didn’t end up raising), but they went unorganized.So, in the U.S. context, many of the numbers we see that are now fully Regular Army came about because the Army divided divisional numbers based on the unit’s provenance—that is, whether it was manned by the Regular Army, by the National Guard, or by draftees. The highest numbered division that was fielded in WWI was the 102nd, but the U.S. didn’t actually field 102 divisions. They were, instead, numbered sequentially based on that provenance: the 82nd was the seventh U.S. division organized for draftees (following the 76th, 77th, 78th, 79th, 80th, and 81st).With WWII, things become even more complicated. Some divisions were fully deactivated, while others remained active, and others (like the 82nd) were moved into organized reserves. Some were revived when the U.S. went to war—for instance, the 82nd was put into active service and retermed the 82nd Airborne. Some simply folded back into their peacetime units—the 28th Infantry Division, for instance, reverted back into being the Pennsylvania National Guard and the numerical designation fell into abeyance only to later be revived as a unit unaffiliated with its WWI counterpart, just as the 28th Infantry Division wasn’t from the Pennsylvania National Guard in WWII.The 14th Infantry Division, meanwhile, was created, but didn’t go overseas, and was eventually disbanded. It, too, was eventually activated during WWII by SHAEF, but it was never manned and eventually disbanded. The 17th Infantry Division was activated in 1917, but, being a National Guard division, was rebranded the 38th Division (because numbers 26–49 were for National Guard war service divisions), but then was recreated in 1918, still as a National Guard division, but didn’t see service. It was reactivated in 1943, but only as a “phantom division”—a fictitious division that was to “take part” in the equally fictitious Pas de Calais landings.Meanwhile, some divisions were reorganized and “demoted” to brigades and linked to another division. For instance, the 41st Infantry Division was “demoted” to the 41st Infantry Brigade, then it was relegated to the Oregon National Guard, then it was attached to the 7th Infantry Division. Then, when the 7th Infantry Division was inactivated in 2006, the 42nd Infantry Brigade continued on as an independent brigade of the Oregon National Guard and served in Iraq and Afghanistan.Some units were simply never organized. For instance, I don’t believe a 72nd Infantry Division was ever activated, even though we have the 82nd.Then you had different forms of divisions, each of which could be numbered independently. So, for instance, you have the 1st Infantry (Big Red One), the 1st Armored (Old Ironsides), and the 1st Cavalry.And then, you have old infantry divisions that no longer function as infantry divisions. The 75th Division, for example, got deactivated in 1957, then reactivated in 1993 as a training support division in the Army Reserve and helped train Reserve and National Guard units going over to Iraq and Afghanistan, and then it got its training units removed to the 84th Training Command and was rebranded the 75th Innovation Command.So… it’s complicated and a lot has gotten lost in the shuffles over the years. The basic logic of why the 82nd is the 82nd, however, is that U.S. divisions were numbered sequentially, but the numbers were assigned “blocks” to designate that unit’s origin, with numbers 76 and up for divisions manned by draftees. The 82nd was the 7th U.S. division manned with draftees, so it was numbered, sequentially from 76, the 82nd Infantry Division. In WWII, it was deemed an Airborne Division, a designation that continues to the present day.

-

How can I fill out Google's intern host matching form to optimize my chances of receiving a match?

I was selected for a summer internship 2016.I tried to be very open while filling the preference form: I choose many products as my favorite products and I said I'm open about the team I want to join.I even was very open in the location and start date to get host matching interviews (I negotiated the start date in the interview until both me and my host were happy.) You could ask your recruiter to review your form (there are very cool and could help you a lot since they have a bigger experience).Do a search on the potential team.Before the interviews, try to find smart question that you are going to ask for the potential host (do a search on the team to find nice and deep questions to impress your host). Prepare well your resume.You are very likely not going to get algorithm/data structure questions like in the first round. It's going to be just some friendly chat if you are lucky. If your potential team is working on something like machine learning, expect that they are going to ask you questions about machine learning, courses related to machine learning you have and relevant experience (projects, internship). Of course you have to study that before the interview. Take as long time as you need if you feel rusty. It takes some time to get ready for the host matching (it's less than the technical interview) but it's worth it of course.

-

How do I fill out the form of DU CIC? I couldn't find the link to fill out the form.

Just register on the admission portal and during registration you will get an option for the entrance based course. Just register there. There is no separate form for DU CIC.

Create this form in 5 minutes!

How to create an eSignature for the division of state fire marshal

How to generate an electronic signature for your Division Of State Fire Marshal in the online mode

How to generate an electronic signature for your Division Of State Fire Marshal in Chrome

How to generate an electronic signature for signing the Division Of State Fire Marshal in Gmail

How to make an electronic signature for the Division Of State Fire Marshal right from your smartphone

How to generate an eSignature for the Division Of State Fire Marshal on iOS devices

How to generate an electronic signature for the Division Of State Fire Marshal on Android devices

People also ask

-

What is florida fire continuing education and how can it help me?

Florida fire continuing education provides essential training for professionals in the fire service to stay updated with industry standards and regulations. Completing these courses ensures that you maintain your certification and enhances your skills, making you more effective in your role. It's not just a requirement; it's an investment in your career.

-

How much does florida fire continuing education cost through airSlate SignNow?

The cost of florida fire continuing education courses through airSlate SignNow varies depending on the course selected. Typically, our pricing is competitive, offering value for high-quality education. It's important to check our website for the latest prices and any available discounts.

-

What features does airSlate SignNow offer for florida fire continuing education?

AirSlate SignNow provides features tailored for florida fire continuing education, including interactive course materials, easy document sign-off, and tracking of your progress. Our platform is designed to simplify the eSigning experience, which enhances the overall education process. It allows you to focus on learning without worrying about paperwork.

-

Are the florida fire continuing education courses accredited?

Yes, the florida fire continuing education courses offered through airSlate SignNow are accredited and recognized by relevant industry authorities. This ensures that your training meets the required standards and is valid for your certification needs. You can trust that our courses will help you fulfill your educational requirements.

-

Can I access florida fire continuing education courses on my mobile device?

Absolutely! AirSlate SignNow's platform is mobile-friendly, allowing you to access florida fire continuing education courses anytime and anywhere. This flexibility makes it convenient for busy professionals to learn at their own pace, without being tied to a desktop computer. Just log in on your mobile device and start learning.

-

What benefits does airSlate SignNow provide for florida fire continuing education users?

Using airSlate SignNow for florida fire continuing education comes with several benefits, including a streamlined signing process for documents and a user-friendly interface. Participants can complete courses quickly without bureaucratic delays, ensuring they remain compliant with certification requirements. Additionally, our customer support team is always available to assist.

-

Is there a money-back guarantee for florida fire continuing education courses?

Yes, airSlate SignNow offers a money-back guarantee for our florida fire continuing education courses if you are not satisfied with your purchase. We are committed to providing quality education, and your satisfaction is our priority. If you encounter issues, please signNow out to our support team for assistance.

Get more for Florida State Fire Marshal Dfs K3 1973 Fillable Form

Find out other Florida State Fire Marshal Dfs K3 1973 Fillable Form

- Sign South Dakota Charity Residential Lease Agreement Simple

- Sign Vermont Charity Business Plan Template Later

- Sign Arkansas Construction Executive Summary Template Secure

- How To Sign Arkansas Construction Work Order

- Sign Colorado Construction Rental Lease Agreement Mobile

- Sign Maine Construction Business Letter Template Secure

- Can I Sign Louisiana Construction Letter Of Intent

- How Can I Sign Maryland Construction Business Plan Template

- Can I Sign Maryland Construction Quitclaim Deed

- Sign Minnesota Construction Business Plan Template Mobile

- Sign Construction PPT Mississippi Myself

- Sign North Carolina Construction Affidavit Of Heirship Later

- Sign Oregon Construction Emergency Contact Form Easy

- Sign Rhode Island Construction Business Plan Template Myself

- Sign Vermont Construction Rental Lease Agreement Safe

- Sign Utah Construction Cease And Desist Letter Computer

- Help Me With Sign Utah Construction Cease And Desist Letter

- Sign Wisconsin Construction Purchase Order Template Simple

- Sign Arkansas Doctors LLC Operating Agreement Free

- Sign California Doctors Lease Termination Letter Online