Simplify Your Busy Invoice Format for Animal Science with airSlate SignNow

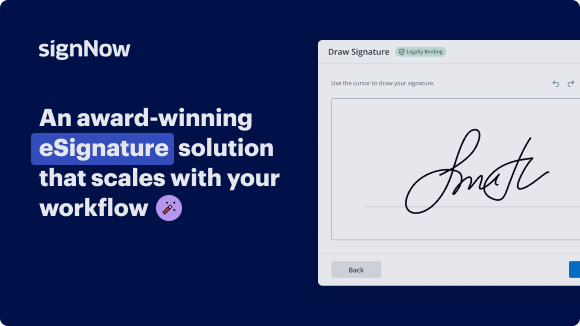

See airSlate SignNow eSignatures in action

Choose a better solution

Move your business forward with the airSlate SignNow eSignature solution

Add your legally binding signature

Integrate via API

Send conditional documents

Share documents via an invite link

Save time with reusable templates

Improve team collaboration

Our user reviews speak for themselves

airSlate SignNow solutions for better efficiency

Why choose airSlate SignNow

-

Free 7-day trial. Choose the plan you need and try it risk-free.

-

Honest pricing for full-featured plans. airSlate SignNow offers subscription plans with no overages or hidden fees at renewal.

-

Enterprise-grade security. airSlate SignNow helps you comply with global security standards.

How to use busy invoice format for Animal science with airSlate SignNow

Managing documents efficiently is crucial in Animal science, especially when dealing with busy invoice formats. airSlate SignNow provides an intuitive platform that simplifies the process of sending and signing documents electronically. This guide will walk you through the steps to leverage its features for optimal productivity.

Steps to utilize busy invoice format for Animal science with airSlate SignNow

- Navigate to the airSlate SignNow website using your preferred browser.

- Create a free trial account or log into your existing account.

- Select the document you wish to sign or send for signature and upload it.

- If you plan to use this document again, save it as a template for future use.

- Access the uploaded file to make necessary edits, such as adding fillable fields or specific information.

- Add your signature and insert the signature fields for others who need to sign.

- Click 'Continue' to set up the eSignature invitation and send it.

Utilizing airSlate SignNow not only streamlines your document management but also offers exceptional value for your investment. With a feature set that aligns with the needs of small to mid-sized businesses, it ensures a flexible and straightforward solution.

Enjoy a clear and straightforward pricing structure without unexpected fees, alongside dedicated customer support available 24/7 for all subscribed plans. Start optimizing your document processes today with airSlate SignNow!

How it works

Get legally-binding signatures now!

FAQs

-

What is a busy invoice format for animal science?

A busy invoice format for animal science is a structured document that facilitates billing for services related to animal health, research, or farming. This format helps ensure clarity in transactions, making it easier for professionals in the animal science industry to organize and document their financial activities efficiently. -

How can airSlate SignNow help with busy invoice formats for animal science?

AirSlate SignNow allows you to create, customize, and send busy invoice formats for animal science quickly and easily. With its user-friendly interface, you can streamline the billing process and ensure that your invoices meet the specific requirements of your industry. -

Is it cost-effective to use airSlate SignNow for busy invoice formats for animal science?

Yes, airSlate SignNow provides a cost-effective solution for creating busy invoice formats for animal science. With competitive pricing options, you can access powerful features without straining your budget, making it ideal for businesses of all sizes. -

What features does airSlate SignNow offer for busy invoice formats for animal science?

AirSlate SignNow offers a variety of features for busy invoice formats for animal science, including customizable templates, electronic signatures, and automated workflows. These tools enhance efficiency and ensure that your invoices are processed quickly and accurately. -

Can I integrate airSlate SignNow with other tools for busy invoice formats?

Absolutely! AirSlate SignNow seamlessly integrates with various software solutions, allowing you to streamline the creation and management of busy invoice formats for animal science. This means you can synchronize your invoicing processes with your existing systems for enhanced productivity. -

What are the benefits of using airSlate SignNow for busy invoice formats for animal science?

Using airSlate SignNow for busy invoice formats for animal science provides several benefits, including increased accuracy, reduced manual work, and faster payment processing. This optimizes your invoicing workflow, helping you focus more on providing quality services in the animal science field. -

Is there customer support available for airSlate SignNow users dealing with busy invoice formats for animal science?

Yes, airSlate SignNow offers robust customer support for users who need assistance with busy invoice formats for animal science. Whether you have technical questions or need help optimizing your invoices, their support team is ready to help you maximize your experience.

What active users are saying — busy invoice format for animal science

Get more for busy invoice format for animal science

- Create Your Payment Confirmation Receipt Template

- Payment Due Upon Receipt Wording

- Payment Invoice Has Been Sent

- Create Your Payment Invoice Sample Easily

- Create Payment Receipt for Construction Work

- Payment Receipt Format for Property Purchase

- Create Your Payment Receipt Letter Easily

- Payment Received Letter Format in Word

Find out other busy invoice format for animal science

- Effortless iPad digital signature app for seamless ...

- Create your unique signature maker for PDF effortlessly

- Access your e-signature account login with ease and ...

- Sign PDF documents online in Chrome effortlessly

- Digitize my signature easily with airSlate SignNow

- Discover our free PDF viewer with digital signature

- Discover the best online signature analysis tool for ...

- Discover HIPAA-compliant electronic signature software ...

- Streamline your workflow with our easy sign application ...

- Discover the best free PDF document sign tool for your ...

- Download free bulk PDF signer for seamless document ...

- Streamline your workflow with our online document ...

- Experience seamless resman portal sign-up for ...

- Effortlessly access signmaster software file download

- Discover the best HIPAA-compliant digital signature ...

- Discover the best PDF reader for multiple signatures

- Discover the best PDF sign tool free online for your ...

- Discover electronic signature solutions for lawyers ...

- Sign and fill online your free PDF document ...

- Discover the best electronic signing software for your ...