Discover Our Money Receipt Sample for Research and Development

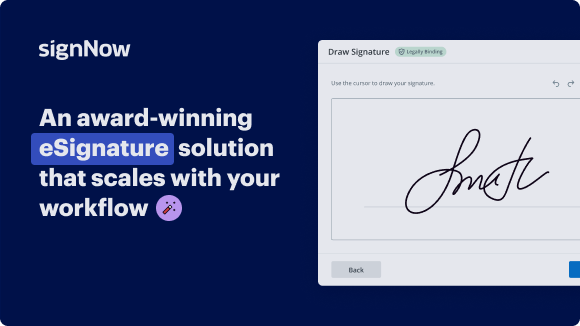

See airSlate SignNow eSignatures in action

Choose a better solution

Move your business forward with the airSlate SignNow eSignature solution

Add your legally binding signature

Integrate via API

Send conditional documents

Share documents via an invite link

Save time with reusable templates

Improve team collaboration

Our user reviews speak for themselves

airSlate SignNow solutions for better efficiency

Why choose airSlate SignNow

-

Free 7-day trial. Choose the plan you need and try it risk-free.

-

Honest pricing for full-featured plans. airSlate SignNow offers subscription plans with no overages or hidden fees at renewal.

-

Enterprise-grade security. airSlate SignNow helps you comply with global security standards.

How to use a money receipt sample for research and development

In today’s modern business environment, having an efficient way to manage documentation is essential, especially when it comes to research and development activities. Utilizing a money receipt sample for research and development can streamline the e-signing process, ensuring that your organization is both effective and compliant. One reliable option is the airSlate SignNow platform.

Steps to create a money receipt sample for research and development

- Open the airSlate SignNow website through your preferred web browser.

- Register for a free trial or log into your existing account.

- Select and upload the document that requires a signature.

- If this document will be used repeatedly, consider converting it into a reusable template.

- Access the file and make necessary modifications by adding fillable fields or relevant information.

- Add your signature and create signature fields for any necessary recipients.

- Click 'Continue' to configure and send the eSignature request.

By implementing airSlate SignNow, businesses can signNowly benefit from a robust return on investment, given its extensive features balanced against cost. This platform is not only easy to navigate but also scales effectively, catering specifically to small and mid-sized businesses.

With clear and straightforward pricing—with no unexpected fees—paired with exceptional 24/7 customer support for all paying plans, airSlate SignNow stands out as a reliable solution for e-signing needs. Start your journey towards streamlined documentation today!

How it works

Get legally-binding signatures now!

FAQs

-

What is a money receipt sample for research and development?

A money receipt sample for research and development is a document used to acknowledge the receipt of funds related to R&D activities. It typically includes details like the amount received, the purpose, and the date, which can help businesses track their expenses accurately. Utilizing a standardized receipt ensures clarity and can aid in financial audits. -

How can airSlate SignNow help with creating a money receipt sample for research and development?

airSlate SignNow allows users to create personalized money receipt samples for research and development quickly. With its intuitive interface, you can customize templates, add necessary details, and save time on documentation. This streamlining of the process ensures that your R&D finances are well-managed and easily accessible. -

What features does airSlate SignNow offer for managing receipts?

airSlate SignNow includes features such as electronic signatures, custom templates, and secure cloud storage for receipts. These functionalities are particularly beneficial when managing a money receipt sample for research and development, as they enhance efficiency and compliance. Plus, you can easily retrieve and track documents anytime, ensuring proper documentation. -

Is there a cost associated with using airSlate SignNow for receipt management?

Yes, airSlate SignNow offers various pricing plans tailored to different business needs. Investing in this solution provides value through streamlined processes and boosted productivity. You can start by trying out a free trial to see how it fits your needs for managing a money receipt sample for research and development. -

Can I integrate airSlate SignNow with other software tools?

Absolutely! airSlate SignNow integrates seamlessly with various popular software tools like Google Workspace, Microsoft Office, and Salesforce. This allows for smooth data transfer and enhances your ability to manage a money receipt sample for research and development effectively across platforms. Integration helps maintain workflow continuity in your business processes. -

What are the benefits of using airSlate SignNow for my business?

Using airSlate SignNow increases efficiency and reduces paperwork in managing documents like a money receipt sample for research and development. The ability to eSign documents saves time and simplifies transactions. Additionally, its cost-effective pricing structure makes it attainable for businesses looking to manage finances better. -

How secure is airSlate SignNow for handling sensitive documents?

Security is a top priority for airSlate SignNow, which implements robust encryption and compliance with legal standards to protect your data. When handling documents such as a money receipt sample for research and development, you can trust that sensitive information is safeguarded. Regular security audits ensure that we maintain high protection standards.

What active users are saying — money receipt sample for research and development

Get more for money receipt sample for research and development

Find out other money receipt sample for research and development

- Unlock Effortless Signatures in Outlook with airSlate ...

- Discover How to Add an Automatic Signature in Gmail ...

- Streamline Your Workflow with Online Signature Copy and ...

- Change Signature in Adobe Acrobat with airSlate SignNow

- Transform Your Document Workflow with airSlate SignNow ...

- Streamline eSigning Process with airSlate SignNow for ...

- Edit Email Signature Outlook 365 Easily with airSlate ...

- Easily Copy and Paste Signature into PDF

- How to Add a Signature to an Email in Gmail Easily

- Discover How to Edit Microsoft Outlook Signature Easily

- How Do I Change My Outlook Email Signature with ...

- Add Signature to Yahoo Mail with airSlate SignNow

- How to Change Your Signature in Adobe with airSlate ...

- How to Change Signature in Adobe Fill and Sign Quickly ...

- Discover How to Edit Signature in PDF with airSlate ...

- Learn How to Add Logo in Yahoo Mail Signature

- Learn How to Edit Digitally Signed PDF with airSlate ...

- Learn How to Update Signature in Office 365 with ...

- How to Add a Logo to Yahoo Email Signature: Simplify ...

- Edit and Sign PDFs for Free with airSlate SignNow