FAA SWIM Program

SOA Governance Best Practices

Industry Input

September 2008

�Acknowledgments

The Federal Aviation Administration has requested industry input on best practices of

implementing SOA Governance for the FAA SWIM program. The Information

Technology Association of America’s GEIA Group includes many industry partners who

support the FAA, and ITAA/GEIA formed a working group to prepare this whitepaper in

response to the FAA request.

Thanks to the following people for contributing to this whitepaper:

Doc. Version:

Editor:

Contributors:

1.0 (09/15/2008)

Mike Moomaw

Organization

Participants

Boeing

Computer Sciences Corp

IBM

IBM

Harris Corp

Harris Corp

Lockheed-Martin

L3 Communications

Oracle

SITA

SITA

Les Robinson

Jay Pollack

Farzin Yashar

Mike Moomaw

Bob Riley

David Almeida

Al Secen

Chris Francis

Peter Bostrom

Kathy Kearns

Mansour Rezaei-Mazinani

About the GEIA Group

The GEIA Group within ITAA develops and distributes forecasts of the Federal

marketplace, creates best-practice industry standards, and maintains a committee

structure through which its member companies work with representatives of FAA and

other Federal agencies on matters of mutual concern. Previously a separate

organization, in 2008 GEIA merged with the Information Technology Association of

America (ITAA) and assumed the ITAA name. GEIA Group contact:

Dan C. Heinemeier, CAE

Executive Vice President, GEIA Group

Information Technology Association of America

1401 Wilson Boulevard, Arlington, VA 22209

www.geia.org/www.itaa.org

703-907-7565 ∙ danh@itaa.org

�Contents

1

FAA Introduction ..................................................................................... 1

1.1

The Role of System Wide Information Management (SWIM) .......................... 1

1.2

A Brief Description of FAA‟s Vision for SOA .................................................. 2

1.3

The Need for a Governing Process Providing the Required Checks and

Balances to Assure Success ............................................................................................ 3

2

Governance Introduction ......................................................................... 5

2.1

Why Governance ................................................................................................ 5

2.2

Enterprise, IT and SOA Governance .................................................................. 6

2.2.1 IT Governance ................................................................................................ 8

2.2.2 Architecture Governance: ............................................................................... 8

2.2.3 SOA Governance ............................................................................................ 8

2.3

Mechanics of the governance model................................................................... 9

2.3.1 Compliance ..................................................................................................... 9

2.3.2 Communications ........................................................................................... 10

2.3.3 Exceptions and Appeals ................................................................................ 11

2.3.4 Vitality .......................................................................................................... 11

2.4

Governance policies and policy management................................................... 11

2.5

Governance standards ....................................................................................... 13

3

Services lifecycle and Governance ........................................................ 14

3.1

The Service Lifecycle Overview ...................................................................... 14

3.2

Initiating SOA Governance............................................................................... 18

3.2.1 Task: Define Charter for SOA Center of Excellence (CoE) ......................... 18

3.2.2 Task: Identify Roles and Responsibilities in Support of SOA ..................... 19

3.2.3 Task: Define Service Ownership and Development Funding Model ........... 19

3.2.4 Task: Identify Success Factors, Enablers and Reuse Motivators ................. 20

3.2.5 Task: Design Policies and Enforcement Mechanisms .................................. 21

3.3

Service Management and Monitoring ............................................................... 21

3.3.1 Service Management in the Context of IT Management and Operations ..... 22

3.3.2 Service Management and Monitoring Tasks ................................................ 23

4

Organizing for SOA & SOA Governance ............................................. 26

4.1

4.2

4.3

5

Program management ....................................................................................... 26

Center of Excellence (CoE) .............................................................................. 27

Roles and Responsibilities ................................................................................ 28

Governance Maturity ............................................................................. 30

5.1

Measurement and Metrics ................................................................................. 32

5.1.1 What should be measured ............................................................................. 32

5.2

Prioritizing Governance Areas .......................................................................... 32

6

Governance Tooling............................................................................... 34

6.1

6.2

7

Governance Vitality ............................................................................... 37

7.1

7.2

8

Identifying Tooling Criteria – Alternative One ................................................ 34

Identifying tooling criteria – Alternative Two .................................................. 35

How is it done and who should be doing it? ..................................................... 37

Events triggering review of the SOA Governance Processes ........................... 37

SOA Governance and FAA ................................................................... 39

�8.1

8.2

8.3

8.4

8.5

8.6

8.7

8.8

8.9

8.10

9

Establish Decision Rights ................................................................................. 40

Defining High Value Business Services ........................................................... 41

Managing Service Life-Cycle ........................................................................... 41

Prepare the Culture ........................................................................................... 42

Measure Effectiveness ...................................................................................... 42

Establish Policies and Procedures ..................................................................... 43

Establish Standards ........................................................................................... 43

Define SOA Architecture .................................................................................. 44

Establish SOA Development Environment ...................................................... 44

Provide SOA Training ...................................................................................... 44

Governance Success Patterns ................................................................. 45

9.1

9.2

9.3

9.4

9.5

9.6

9.7

9.8

9.9

9.10

Assure Executive Sponsorship/Champion ........................................................ 45

Create Real or Virtual/Interim CoE .................................................................. 45

Communicate Business Values ......................................................................... 45

Grow into SOA, Don‟t Jump Into It. ................................................................ 46

Adopt Policies ................................................................................................... 46

Measure every step of the way.......................................................................... 46

Employ Tooling and Establish a SOA Lab ....................................................... 46

Understand your Maturity Level ....................................................................... 47

Create and Govern a SOA Roadmap ................................................................ 47

Govern the Return of Investment ...................................................................... 47

Appendices .................................................................................................... 48

Appendix 1 – FAA SWIM Acronyms .......................................................... 48

�1 FAA Introduction

While current economic conditions, heightened security concerns, and higher energy

costs have temporarily dampened the growth in demand for air transportation, air traffic

is still expected to double or triple within the next twenty plus years. This projected

growth in demand is and will continue to be increasingly problematic for the National

Airspace System (NAS). Not only are airport, runway, and terminal resources limited,

but NAS legacy Air Traffic Control (ATC) systems, still based largely on 1950s

technology and point-to-point communication interfaces, will be incapable of handling

the projected increase in air traffic operations.

In recognition of the increasing urgency for more rapid modernization of the Nation‟s air

traffic control system, the FAA has recently created a new leadership position, Senior

Vice President of NextGen and Operations planning. To better coordinate the efforts of

several Federal Departments and Agencies and to ensure more rapid implementation of

critical near- to mid-term NextGen-enabling programs, the FAA has also incorporated the

Joint Planning and Development Office (JPDO) into the new organization. Among those

programs identified as critical NextGen enablers is SWIM (System Wide Information

Management).

1.1 The Role of System Wide Information Management (SWIM)

The NAS is an assembly of intricate systems that has been independently structured and

has multiple users with varying needs and access requirements. An orderly evolution

from today‟s sum-of-systems to a system-of-systems approach is a key to NextGen.

SWIM is a foundational element and key enabler of that evolution.

Through widespread information sharing and access within a modern and efficient

networked infrastructure, SWIM can make Air Traffic Management (ATM) information

ubiquitous and timely. By ensuring that users and service providers share a common

operating picture and immediate access to all information required to make effective

decisions, SWIM will provide a basis for enhanced NAS agility, increased operating

efficiency, and improved system safety. Through virtual collaboration and intelligent

automation, this shared awareness will in turn enable the NextGen operations

transformation.

The FAA has developed the SWIM concept to support loosely coupled, many-to-many

data exchange interfaces of the type that NextGen operations will require. The specific

goals of SWIM include improved sharing of information (leading to better decisionmaking and operational effectiveness), improved systems integration (reducing functional

redundancy and improving information quality), and greater flexibility to accommodate

the system and operational changes required for NextGen.

The economic benefits to the FAA can be substantial. For example, managing air traffic

requires the skills of many people and the capabilities of many software applications

(programs). Each of these applications requires information from one or more sources to

perform its task and may in turn provide information for others. Over time, it has become

FAA SWIM: SOA Governance Best Practices – Industry Input (ITAA/GEIA Group)

Page 1

�increasingly necessary to integrate new combinations of applications for improved air

traffic management capability and increased NAS capacity. Historically, application

integration has been a very labor-intensive (expensive) process involving modifications

to each of the applications being integrated. For example, if an existing integrated group

of five applications were to have a sixth application added; this could require

modifications to all six applications. As the number of applications requiring integration

grows, this integration process rapidly becomes infeasible.

SWIM can play a significant role in reducing FAA costs by addressing this scalability

issue. Instead of developing and implementing specific solutions for securely sharing data

between application pairs, SWIM implements a common infrastructure and set of

processes for sharing and managing data within the NAS. Once data is published on

SWIM, the data is made available for any authorized application to discover and use.

SWIM employs modern enterprise application integration patterns that are based on an

underlying set of technologies allowing applications to be integrated without

modification. These technologies consist of a common hardware and software

infrastructure, coupled with extensible application interfaces that allow the integrated

applications to interact. New applications can be developed that have these interfaces

and existing applications can be augmented by an adapter that provides the necessary

interface without modifying the original application itself.

1.2 A Brief Description of FAA’s Vision for SOA

The FAA‟s vision for Segment 1 of SWIM includes the concept of a “Service Container

(SC) that will provide certain SOA capabilities and will be distributed in nature – located

at each of the SWIM Implementing Programs (SIPs).

As described in an earlier GEIA Group white paper i, this raises several “boundary”

questions:

1. Which SOA elements will reside inside the Service Container?

2. Which SOA elements will reside in the SIPs but outside their Service Containers?

3. Which SOA elements will the FAA provide centrally?

4. Which SOA elements will the FAA provide in a federated fashion – by the SIPs?

Answers to these questions may change over time as the FAA gains experience from

“early adopters” of SWIM services and adjusts the solution to deliver maximum value to

FAA stakeholders.

In Segment 1, SWIM will not create many central resources for implementing programs.

There will not be a central ESB providing messaging, security, and similar functions;

instead – for the most part – the responsibility of implementing these core (infrastructure)

capabilities will belong to NAS programs such as ERAM and TFM-M. There are two

areas where the FAA does envision creating centralized services during Segment 1: (a) a

FAA SWIM: SOA Governance Best Practices – Industry Input (ITAA/GEIA Group)

Page 2

�design-time registry to assist in common service access; and (b) test bed capabilities to

support interoperability testing.

Keeping an eye toward the future – beyond Segment 1 – is important, however. While

Segment 1 may not create a large number of centralized services, it is possible that future

Segments will expand this pool of services. The Service Container can play a key role in

delivering this flexibility to FAA programs by acting as a service wrapper to provide

attachment points for security, messaging, service management, and interface

management capabilities (and possibly other SWIM services in future Segments). The

lightweight SC will not provide these capabilities, but will provide a standard mechanism

for connecting them to services.

As SWIM architecture evolves, the SC will help enable interoperability in future FAA

Segments. It is likely that the distribution of services will change over time –possibly

gravitating toward the centralized pool. The SC can help provide continuity for FAA

programs as this re-distribution of service-fulfillment occurs. Even in Segment 1, services

will need infrastructure capabilities, and during Segment 1 those services will likely be

fulfilled via existing FAA programs for services such as for authentication and

authorization, service monitoring and management, message queue management, etc.

The SC will provide a wrapper that supports a seamless transition from program-provided

infrastructure to SWIM-provided infrastructure in the future. The key is flexibility: while

the SC construct does not obligate the FAA to changing the location of services, it

provides the FAA with the ability to re-locate certain services in the future if such

relocation would be beneficial.

In many cases the SOA Framework components can be decentralized and federated to

support the Service Container concept. However, since decentralized, federated

components tend to add complexity and risk over centralized solutions, consideration

should be given to architectures that include centralized components where consistent

with the FAA‟s operational needs.

Since the Service Container concept by itself permits, but does not require, centralized

hosting of services, FAA stakeholders will need to consider an appropriate balance

between an enterprise-wide SOA and a federated model. The best solution for the FAA

may well lie somewhere in between, with some services centralized and others federated.

The choices to be made will in some measure determine and be determined by the SOA

benefits the FAA decides it must provide through SWIM to support NextGen operations:

just system-interfaces, or others such as Workflow Orchestration, Business Process

Modeling, and Business Activity Monitoring. These choices can be facilitated through

use cases and trade studies.

1.3 The Need for a Governing Process Providing the Required

Checks and Balances to Assure Success

This white paper is not intended to address the broad topics of either enterprise

governance or IT governance but is instead confined to consideration of SOA

governance. SOA Governance may be viewed as an augmentation of IT governance

FAA SWIM: SOA Governance Best Practices – Industry Input (ITAA/GEIA Group)

Page 3

�since it is primarily focused on business services strategy and on the lifecycle

management of services (single services as well as the network of services) to ensure

their business value to the enterprise ii.

Moving to SOA represents a substantial challenge for organizations. Besides introducing

new technologies and responsibilities, SOA requires a change from application-based

thinking to an enterprise-wide perspective intended to control how workflows are

accomplished and how services and a portfolio of services are developed, deployed and

managed throughout their lifecycle to accomplish enterprise business objectives.

SOA governance certainly should include elements of enforcement, control and policing,

but it needs to be much more. Since a primary SOA objective is the identification,

development, deployment and lifecycle management of services (and portfolios of

services), SOA governance cannot be rigid or autocratic but must become a collaborative

effort involving centralized IT management with the active participation of internal (and

external, if required) communities of interest (COIs).

The importance of involving Communities of Interest in the SOA Governance process

cannot be overestimated. Many of the benefits of SOA are based on the sharing of

services, as well as the sharing of information, best practices architectures and business

processes and objectives. For this reason, strong consideration should be given to the

early adoption of a federated SOA Governance model. This should include the early

establishment of a Core SOA team, or SOA Center of Excellence (COE), whose role is

one of collaboration with the SWIM Program Office to share needs, services, and

resources for the good of the enterprise.

Collaboration between semi-autonomous, interconnected business units is often difficult.

To overcome this natural institutional friction, SOA Governance can begin informally

and on even an ad hoc basis, but it should naturally progress over time to more

formalized oversight with standards, best practices, and enterprise alignment as its

ultimate goal. A key element in making this collaborative process work is, of course,

executive level buy-in. Without the commitment of both leadership and enterprise

communities of interest, the potential benefits of SOA can be easily lost.

FAA SWIM: SOA Governance Best Practices – Industry Input (ITAA/GEIA Group)

Page 4

�2 Governance Introduction

Good governance is all about transparency - ensuring that everyone involved in an

activity clearly understands their individual roles and responsibilities, what expectations

the other team members have of them, and how they personally contribute to the overall

goals. In this section we examine the importance of governance and we define SOA

governance and its relationship with Enterprise as well as IT Governance.

2.1 Why Governance

One definition of governance is “the set of rules, practices, roles, responsibilities and

agreements – whether formal or informal – that control how we work”. In another words,

for each activity we need to define:

What needs to be done

How it should be done

Who should do it

How it should be measured

As obvious, trivial and self-evident the above may be, in many cases these precepts are

not being followed. They are either eliminated or compromised in the name of SPEED,

(“Just do it”).

The key phrase in the above definition is “control how we work”. This level of control

can be at a level anywhere from very light and unobtrusive control (guidance) to a very

tight and bureaucratic level of control (policing). Neither does the work of governance

mean management, per se. Governance determines who has the authority to make

decisions. Management is the process of making and implementing the decisions.

If we think about the What, How, Who, and measurement of the standard IT project, we

see that these functional attributes are not always well defined either. The business

reasons for having an Information Technology (IT) function has come about to bring

agility to what the business does. But IT implementation has always faced the dilemma

of not being a fast and agile process itself. Therefore, IT projects are very much prone to

temptations of cutting corners and eliminating and bypassing vital steps. Many times, the

“What” of an IT Project, in the form of functional and non-functional requirements, are

not complete and it is left to the imagination of the IT individual(s)/department on what

should be created. The “How” is normally influenced by individual styles and

preferences. The “Who” could end up with whoever is available. Measurement of the

project results will usually not happen as the development team moves onto the next

project.

So while the state of IT Governance leaves something to be desired, we are now faced

with the challenge of migrating to a services approach with SOA. Moving to SOA

represents a considerable challenge for any organization, especially since: SOA

introduces new technologies, roles and responsibilities; SOA requires new patterns of

FAA SWIM: SOA Governance Best Practices – Industry Input (ITAA/GEIA Group)

Page 5

�thought – taking an enterprise-wide viewpoint, rather than focusing on any one

department, or specific Line of Business (LOB) area.

The potential benefits of SOA may not be achieved without the enforcement rigor around

development, deployment and operational management of services across the enterprise.

Lessons learned from past attempts at SOA indicate that the mere proliferation of

services in the absence of governance policies will not realize a Service Oriented

Architecture. Lack of SOA governance impacts any organization‟s ability to realize the

potential benefits of service orientation, by allowing inconsistencies, gaps and overlaps in

the software development process that makes reuse and business agility difficult, if not

impossible. Thus, without governance, the SOA journey is likely to fail.

Implementing SOA successfully at FAA will create new and additional challenges to

people, process and technology that must be addressed through sound and effective

governance. Without such governance, business agility is impossible, service ownership

will remain locked within silos, portfolio management will remain balkanized and

ineffective, and security will be in islands instead of achieving a more holistic, enterprisewide view.

2.2 Enterprise, IT and SOA Governance

SOA governance extends, or augments IT governance further aligning IT and business by

governing the lifecycle of business services as manifested in IT systems. Deploying SOA

should serve as a catalyst for an organization to start thinking about improved corporate

and IT governance in general, as well as how to best implement SOA governance

practices specifically. Adoption of SOA raises new issues in IT decision rights,

measurement and control.

SOA governance augments IT governance as enterprises focus further on ServiceOrientation adoption. SOA provides a distinctive enterprise-level approach for designing

and delivering cross functional initiatives, closely involving both business and IT in the

collective pursuit of the enterprise‟s strategy and goals. This form of SOA governance

introduces the use of business policies, both enterprise-level and department level policy

invocation, which provides the discipline referenced above.

Establishing SOA Governance should also be seen as providing another opportunity to

bridge any gaps between enterprise and IT governance. SOA governance would benefit

from existing IT and Enterprise governance. However, lack of existing IT and Enterprise

governance, or “operationalizing” the IT & Enterprise governance practices should not

stop enterprises from establishing SOA governance. In many cases, the need for SOA

governance has encouraged enterprises to revisit and reinvigorate their IT and Enterprise

governance.

FAA SWIM: SOA Governance Best Practices – Industry Input (ITAA/GEIA Group)

Page 6

�Today

SOA

Governance

Corporate

Governance

IT Governance

Corporate

IT

Overlap

Tomorrow

SOA Governance

Adoption and

Execution

Corporate

Governance

IT Governance

SOA

Governance

Figure 2.1- Enterprise, IT and SOA Governance

Conceptually, the way that the relationship between Enterprise, IT, and SOA governance

changes over time is shown in figure 2.1 above.

Initially, SOA governance has limited scope and concerns itself mainly with a fairly

limited area where IT and Business interests overlap.

As the organization increases its level of SOA maturity, the scope of SOA governance

will expand significantly. The business and IT communities should gradually increase

their degree of overlap until eventually an expanded SOA governance role merges with

IT governance, and IT governance itself is subsumed into an overall corporate approach

to governance.

Generally speaking, enterprise level governance establishes the rules and the manner in

which an enterprise conducts its business. Enterprise governance includes establishing

compliance goals, its strategy within the marketplace, according to its principles of doing

business. IT governance represents a significant portion of enterprise governance, due to

the horizontal nature of IT and the broad reliance on IT around the world. Since almost

everyone in an enterprise uses IT assets to complete their responsibilities, and all

persistent information is stored in IT systems, the impact of effective IT governance is

highly visible.

FAA SWIM: SOA Governance Best Practices – Industry Input (ITAA/GEIA Group)

Page 7

�SOA Governance typically defines additional nuances and changes to IT Governance to

ensure that the concepts and principles for Service Orientation are managed appropriately

and that the organization is able to deliver on the stated business goals for SOA. In

addition, SOA Governance drives organizational change for better partnering between

business and IT in order to achieve a higher degree of business value by optimizing

return on investments and improving business agility. This is done by associating

business requirements with business services instantiation. This association, if conducted

rigorously, results in better risk management and predictability in all phases of IT system

implementation.

Since SOA is a distributed approach to architecture that may span multiple lines of

business domains (internal and external) as well as IT domains there is a greater need for

effective SOA governance. In addition SOA Governance provides a framework for the

reuse and sharing of services, a key value derived from leveraging SOA.

2.2.1 IT Governance

IT Governance can be defined as:

Establishing and implementing decision making rights associated with IT.

Establishing mechanisms and policies used to control and measure the way

IT decisions are made and carried out.

One of the most important aspects of IT Governance is Architecture Governance, which

is defined below.

2.2.2 Architecture Governance:

Architectures are controlled at an enterprise-wide level by practicing architecture

governance. Enterprise Architecture (EA) plays a significant role in governance as the

EA discipline defines and maintains the architecture models, governance and transition

initiatives needed to effectively coordinate semi-autonomous groups towards common

business and/or IT goals.iii

2.2.3 SOA Governance

SOA governance is an augmentation of IT governance focused on:

Business services strategy

Lifecycle of services to ensure the business value of SOA

Enablement of the services approach

Aligning business and IT governance towards the goal of achieving business

objectives.

SOA Governance is frequently a catalyst for improving overall IT governance,

particularly in large organizations with a reliance on legacy IT infrastructure.

FAA SWIM: SOA Governance Best Practices – Industry Input (ITAA/GEIA Group)

Page 8

�2.3 Mechanics of the governance model

SOA governance ensures successful Business and IT alignment. It enforces agreed upon

Policies and Standards. These policies and standards guide the governed processes that

are managed and monitored by governing processes, standards and metrics; and

implemented by procedures.

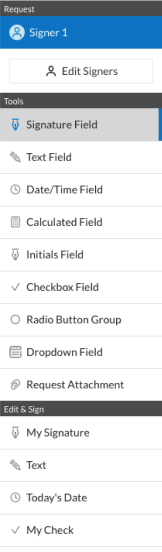

Figure 2.2 points out Compliance, Communication, Vitality and Exceptions/Appeals.

These are the most important mechanisms in governance. We address each of them

separately.

Business

Principles

IT

Principles

Compliance

Policies

Guide

Standards

Vitality

Managed by

Governing

Processes

Implemented by

Monitored by

Procedures

Standards &

Metrics

Communication

Governed

Processes

Supported by

TOOLS

TRAINING

Exception/Appeals

Figure 2.2 Mechanics of Governance

2.3.1 Compliance

Governed processes are guided by policies and standards. Defining policies and

identification of standards have a significant importance for governance best practices.

However, policies and standards without compliance marginalizes their value. To this

end, concepts such as control points, Policy Decision Points and Policy Enforcement

points are essential in governance. Section 2.4 is dedicated to policies and policy

management for this purpose.

FAA SWIM: SOA Governance Best Practices – Industry Input (ITAA/GEIA Group)

Page 9

�2.3.2 Communications

Clear communication is essential to governance. Communication is needed within the

enterprise as well as with partners, providers/suppliers and clients. Communication is

about delivering the right message, to the right people, at the right time. It is a key

enabler to moving people through the various stages of any process requiring awareness,

understanding, commitment and adoption.

Air Traffic Services are governed by the International Civil Aviation Organization

(ICAO) Convention under which states commit to providing ATS services in their

airspace over their territory and the surrounding oceans.

On a day to day basis civil aviation authorities communicate with each other and with

airlines and airports for the exchange of operational messages such as flight plans,

weather messages etc. The current legacy messages are exchanged through AFTN

(Aeronautical Fixed Telecommunication Network).. AFTN is created by the Air Traffic

services providers, following ICAO standards, and has a messaging address structure

based on ICAO codes. It now comprises some 150 national networks with connections to

their national terminals and those in adjacent countries. AFTN traffic consists of

NOTAMS, Flight Plans and Slot Allocations, and operational meteorological data. It

circulates on the internal AFTN network, between different ATS providers, and between

providers and airlines. Within FAA this is achieved through the FAA

Telecommunications Infrastructure (FTI) Network

A new generation of ICAO messaging referred to as the Aeronautical Message Handling

System (AMHS) is finalized in 2002 as part of the ICAO standard for the Aeronautical

Telecommunications Network (ATN). The AMHS uses a set of protocols derived from

the ITU X.400 standard. AMHS systems can interconnect using the X.25 protocol, or the

planned ATN networks that will use OSI protocols or to use AMHS over TCP/IP using

RFC1006. The deployment of AMHS is slow due to its questionable aging technology.

While AFTN messaging has served the ICAO community well, it is not extensible to

meet the needs of more demanding newer applications with much more complex data.

Additionally it remains an aging technology that requires serious replacement. AMHS

which is based on X.400 has been recommended to replace AFTN. However it remains

yet another outdating technology with high cost of deployment, scare expertise and

products. And while there are AFTN and AMHS approaches that leverage the benefits of

IP networks, current implementations in the industry are still constrained to using costly

network technologies such as X.25 or CLNP routers.

Airline exchanges are governed by IATA/ATA standards. The current industry reliable

messaging for business critical exchanges use an IATA standard referred to as TypeB.

Gateways are also developed to bridge AFTN to TypeB and consequently enable

seamless message communications between ATSOs and airlines.

Leveraging open standards such as XML based messaging and using the Web Services

communication framework has the potential to transform how business class messaging

is accomplished in the industry through new technology use. For air transport operational

messaging a new standard called TypeX is under finalization with the related IATA

Work Group that specifies the use of industry standard addresses and compliant with

FAA SWIM: SOA Governance Best Practices – Industry Input (ITAA/GEIA Group)

Page 10

�IATA and ICAO codes is emerging to support XML messaging and industry business

practices. TypeX has been implemented by SITA and ARINC and some users. TypeX is

SOAP based and can be used in a SOA environment and plugged into ESB. TypeX

makes use WS-* security specifications for security functions

The use of TypeX by FAA for communication with the other civil aviation authorities

and airlines meets the directions defined within the scope of SWIM. It facilitates

communications by the use of a single protocol that meets ICAO and IATA messaging

and addressing requirements while making use of a widely supported open technology.

Communications with AFTN and airlines TypeB is facilitated by gateways that are

simple to build due to similarity in addressing and some other industry related technical

principles.

2.3.3 Exceptions and Appeals

Governance should not be a set of static processes without any flexibility. As part of the

governance life cycle, governance processes may be appealed, or waived as exceptions

require. In managing and monitoring policies and standards compliance, an appeal, or

waiver process needs to be built for cases where achieving compliance is either

temporarily or permanently impossible. Appeals, or waivers are a very sensitive topic,

because on the one hand it has to be flexible enough to accommodate these exceptions,

while on the other be stringent enough prevent unnecessary exceptions that may set

uncontrollable precedence.

2.3.4 Vitality

As time goes by things will change and governance processes must adapt. This is called

vitality. We have dedicated section 7 to governance Vitality.

2.4 Governance policies and policy management

Business process management (BPM) drives the creation of services through the

identification, definition and creation of service operations. Compliance with the many

rules and laws becomes a key driver behind governance. These service operations have

design time and run time business processes that should be mapped, and benchmarked

with key performance indicators established to enable service level agreements, based on

Quality of Service (QoS) parameters.

Policy management provides a mechanism to allocate IT resources according to defined

policies, or rules established by the enterprise. Policies dictate the data quality, integrity

and retention requirements. Policies allow rules to take the form of if, then conditional

statements, where actions are executed to account for a given condition. Within the

context of SWIM, specific policies must be established by the NAS application program

(the individual enterprise). The application program best understands the NAS

requirements used to establish data integrity, retention and accessibility requirements.

Hence, the application program must be empowered to establish their formal program

policies into procedures which are implemented into systems, tools for execution.

Policies are built into systems establishing policy decision points (PDPs), where events

are defined and decisions made. The PDP‟s are configured to support various conditions

and react accordingly. PDP‟s are synchronized with policy enforcement points (PEPs),

FAA SWIM: SOA Governance Best Practices – Industry Input (ITAA/GEIA Group)

Page 11

�which monitor for events, and execute the policies as defined by the NAS Application

Program in the FAA, within the context of the PDP. The monitoring and control

function, discussed in the next paragraph, provides a centralized PEP capability designed

to collaborate with decentralized PDP‟s. To support the many application programs

within the NAS, the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) has defined standards for

localizing policy decision points, enabling a decentralized enterprise support structure,

while integrating into a higher level policy management system.

Policy enforcement points exist within the network and IT infrastructure used for

monitoring events. A myriad of tools are required to provide the proper IT governance

and access control at a macro level. Each application program must support their own

infrastructure; however, the key to a service-oriented architecture is the agility of data

transport to new communities of interest. Tools for web services management, including

service registries, repositories and metadata catalogs, asset tracking and

fault/performance monitoring are required to enable the policy enforcement function.

The IT Infrastructure Library (ITIL) standards define a configuration management

database (CMDB) which hosts these data elements that require tracking. The IT tools are

required to collect and report on the many data transactions, tracked to individual users,

along with key performance indicators, and then report them accurately to the NAS

Application Program.

Here are some policy examples:

Policies might start at the business level:

o Projects must comply with Internal Architecture guidelines

o Security and regulatory compliance policy reviews are mandatory for all

IT projects

Policies could represent more specific regulatory compliance issues:

o Patient personal identifiable information must be communicated and

stored securely. (HIPPA)

o All financial transactions must provide traceability and tamper proof

mechanisms for mandatory audit records. (Sarbanes Oxley)

Project outsourcing initiative might represent its policy as:

o Outsourced company must create same service lifecycle deliverables as

are created in house.

Higher level policies will often need to be translated to technical policies that can

be effectively enforced by active policy enforcement tools.

Information security examples:

o Messages must contain an authorization token

o Password element lengths must be at least 6 characters long and contain

both numbers and letters

o Every operation message must be uniquely identified and digitally signed

FAA SWIM: SOA Governance Best Practices – Industry Input (ITAA/GEIA Group)

Page 12

�

There are also design related technical policies that are needed to ensure

interoperability and reuse:

o Do not use RPC encoded style web services

o Do not use Solicit-Response style of web service operations

o Do not use XML „anyAttribute‟ wildcards

Each organization, as part of the strategy and planning process for SOA, should

think about and create its set of standards and policies for its SOA program and

the SOA service development lifecycle. Specific policy service examples follow.

The Service Specification should contain:

o Descriptions of what function is performed by each service operation

o Input/output message formats, and sample data for each service operation

o A definition of the corresponding task in the Component Business Model

(CBM)

The Service Specification should NOT contain:

o Any information on how the service will be implemented (provided the

service contract is maintained, the provider may change the

implementation of the service at any time, e.g. when retiring an obsolete

IT system)

o Any reference to a sequence or order in which operations should be

executed. Each operation call should be considered as a discrete task, and

sequences of tasks should be defined as business processes/automated

business processes) in separate documentation

2.5 Governance standards

A standard is a rule or requirement that controls the service lifecycle. The governed

service must adhere to the standard. Standards change very infrequently and a violation

is not allowed or requires an explicit exception. In case an organization decides to

deploy web services, the following table could be example of standards they may

designate to follow:

FAA SWIM: SOA Governance Best Practices – Industry Input (ITAA/GEIA Group)

Page 13

�Standard

Orchestration

Recommended

BPEL

Management

Security

WS-Security

Proposed Alternatives

WS-Choreography

WS-CDL

WS-DistributedManagement

WS-Provisioning

WS-Trust

WS-Federation

WS-Management

WS-Transaction

WS-Coordination

WSCompositeApplicationFramework

(WS-CAF)

Reliability

WS-ReliableMessaging

WS-Reliability

Description

WSDL

UDDI

WS-Inspection

Disco

WS-Discovery

WS-Addressing

WS-Notification

WS-ResourceFramework

Transaction

XML

SOAP

Messaging

Transport

Interoperability

HTTP

JMS

RMI-IIOP

WS-1 Basic Profile

TCP

UDP

WS-SecureConversation

WS-SecurityPolicy

WS-Context (WS-Ctx)

WS-CoordinationFramework

(WS-CF)

WS-PolicyFramework

WS-MetaDataExchange

ES-Eventing

WS-Policy

SOAP with Attachment

MTOM

DIME

Jabber

SMTP

Table 2.1 – Examples of Standards for Web Services

SOA borrows concepts such as Policy, Service Level Agreement and Quality of service

from other aspects of Information Technology such as network management and

managing IT infrastructure. Since at this time there is no SOA policy management and

policy related standards in place, reference to standards defined by IETF (Internet

Engineering Task Force) and or ITIL (Information Technology Infrastructure Library) is

highly recommended.

3 Services lifecycle and Governance

Services are the heart of the Service Oriented Architecture. Therefore, SOA governance

has a special focus on governing services. In this section we define the lifecycle of

services and we discuss the fundamental tasks for establishing governance.

3.1 The Service Lifecycle Overview

All services go through a consistent set of steps, starting from the creation of an original

concept, all the way through analysis, design, development, testing, deployment then

eventual retirement, as shown in figure 3.1 below:

FAA SWIM: SOA Governance Best Practices – Industry Input (ITAA/GEIA Group)

Page 14

�INDEX

Old Service State

Conceptual

Action or Activity

analysis

New Service State

Outlined

Deferred or Discarded

Funding Decision

Pre-requisite service

identified

Funded

Retirement Decision

In Repository

In Registry

Specification

Planned

Detailed Design

Deprecated

Designed

Build & Test

Constructed

Re-Versioned

Rework Required

Acceptance Test

Ratified

Deployment

Operational

Figure 3.1 - The Service Lifecycle State Diagram

This is actually a state-transition diagram in which each valid state is well-defined, and a

specific activity has to be performed in order to move from one state to the next.

Like all models, this represents a simplified view of reality: there are no intermediate

states like „under development‟ for example, since the definitions of such states are

subjective and ambiguous.

This development model, however, is an excellent model to define a SOA development

approach:

Each activity that causes a transition from one state to another can be well

defined, and then assigned to a suitably-skilled individual or team to be

performed repetitively and to a continuously high standard.

Since the stable states can be well-defined, it is practicable to have Quality

Assurance (QA) reviews (sometimes known as „control gates‟ or „control

points‟) to determine that each activity has been performed to sufficient

quality for migration to the target state to be confirmed reliably

Since the activities are repeatable, it is possible to both predict and monitor

the development work efforts of an IT solution that requires a significant

number of services to be deployed

FAA SWIM: SOA Governance Best Practices – Industry Input (ITAA/GEIA Group)

Page 15

�The main stages in the service lifecycle are:

Identification – When the initial need is recognized and the requirements are

specified

Specification – When the detailed requirements and high-level design are

captured

Realization – When the service is constructed and deployed

Operation – When the service is managed through the rest of its lifetime until

it is eventually re-versioned or retired

It is important to notice that not everything can be made into a service, and not all

services could, or should be exposed. As part of governing the SOA lifecycle, candidate

services need to conform to a service litmus test, whose answers can establish a set of

criteria to qualify a service. This litmus test contains questions such as: Is this service

reusable and how many consumers will it have? Is this service in line with the goals of

the enterprise?, and so on.. Once a candidate service is selected, then the next step is to

decide if it should be exposed. Exposure of a service means availability for consumption

by others in a visible manner, such as through a registry. There are many reasons for not

exposing a service. For example, infrastructure services may not be required enterprisewide and, therefore, not exposed; or, security restrictions and policies may drive the

enterprise to expose a service for visibility to only a select set of users.

The service lifecycle is consistent with software/system development methodologies

(SDM), like rapid application development (RAD), Rational Unified Process® (RUP®),

iterative, spiral and even agile development methods. For example, the Rational Unified

Process® (RUP®) consists of the following four incremental phases:

Inception

Elaboration

Construction

Transition

Effectively, these phases are performed for each service being created. The phases are not

an exact match because the operation stage of the service lifecycle extends somewhat

beyond the RUP transition phase.

FAA SWIM: SOA Governance Best Practices – Industry Input (ITAA/GEIA Group)

Page 16

�Figure 3.2 - RUP Phases

The following diagram depicts the service lifecycle in detail. As indicated, the orange

boxes are QA-related steps to ensure effective governance of the SOA development

process. The orange boxes could be considered Policy Enforcement Points (PEP). For

example, we could have a policy stating that acceptance testing must have 95% success

rate prior to exposing the service enterprise-wide. Also, please notice that the bottom

part of figure 3.3 shows activities that are not part of an SDM, meaning current

methodologies should be extended, or augmented to embrace SOA.

FAA SWIM: SOA Governance Best Practices – Industry Input (ITAA/GEIA Group)

Page 17

�New Candidate Operations

Prioritized

CBM

Process

Models

Existing

Systems

Candidate

Consumers

Identified

Search for

Existing

Implementation

Operations

Specified

Identify

Service

Providers

Triage &

Prioritize

Operations

OL Operations “build

Review &

Publish

Operations

List

list”

Deferred or

OL rejected

Operations

Service Identification(RUP Inception)

OL

Create Service Specification

Info

Model

Document Provider Interfaces

Existing

Systems

OL

Service HighLevel Design

Review

SP

Document High Level Design

Service Specification(RUP Elaboration)

Process

Models

RUP Construction

Operations

List Updates

Business

Services

Portfolio

SS

Service Specification

IS

Service Provider

Interface

Specification

SDD

Service Design

Document

code

Code-related

artifacts

RUP Transition

SS

IS

Develop

Components

SDD

Create

Deployment

Unit

Integrate &

Test

Acceptance

Test

Create

Product to

Release

Service Realization

INDEX

code

Certify &

Publish

Service

Monitor SLA

Compliance

Operational

Service

Plan New

Service

Version

Deprecate

Service

Process

Decommission

Service

Service Operation

Governance

Figure 3.3 -The Complete Service Lifecycle in Detail

(Component Business Model (CBM), Service Level Agreement (SLA))

3.2 Initiating SOA Governance

In order to establish SOA governance, a few fundamental tasks need to be considered.

3.2.1 Task: Define Charter for SOA Center of Excellence (CoE)

Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.org/) defines “a Center of Excellence (CoE) or Center

of Competence as the formally appointed, and informally accepted, body of knowledge

and experience on a subject area. It is a place where the highest standards of achievement

are aimed for in a particular sphere of activity”

The SOA CoE is comprised of People, Process, Technology and Services and provides

the leadership for successful implementation of services in the enterprise.

Essentially, the SOA CoE‟s primary mission is change management: Everyone involved

in the CoE, from the executive leading it to the professionals that design, develop and test

services, needs to be an agent of change.

FAA SWIM: SOA Governance Best Practices – Industry Input (ITAA/GEIA Group)

Page 18

�The SOA CoE should aim to establish services as key enterprise assets by:

Providing leadership in SOA vision and execution through a single, crossorganizational, cross-functional authority for SOA related planning and

implementation

Creating and nourishing expert level SOA skills towards best practices,

technology, standards and related SOA methodologies

Recommending and helping mobilize organizational and governance models

for ongoing SOA adoption

Meeting the agreed target maturity level of service-orientation within the

lifetime of the CoE

Designing infrastructure enhancements for managing the usage of services in

areas of security, monitoring, performance, versioning, and shared usage

Providing enhancements to IT processes to address funding, sharing, and

incentives for sharing and reuse of services as well as for the identification,

design and specification of services

Helping plan education and training to broaden SOA delivery skills

Communicating the strategic intent of the IT department to develop SOA

competency into a strategic, core competency for the long term competitive

advantage of the organization as a whole

3.2.2 Task: Identify Roles and Responsibilities in Support of SOA

Like any transformation, SOA adoption introduces new challenges. Successful adoption

of Service-Orientation requires changes to organizational roles and responsibilities. FAA

must invest time and effort in creating an appropriate organization and support structure

to enable a smooth adoption of SOA principles. A first step is establishing a Center of

Excellence (CoE) focused on SOA.

We will discuss CoE in detail in a separate section. It is suffice to say the SOA

introduces new roles and responsibilities such as Service Registrar or Service Architect.

3.2.3 Task: Define Service Ownership and Development Funding

Model

A clear understanding and communication of funding and ownership models is necessary

to ensure an optimal adoption rate for SOA. The funding model should be established in

so as to encourage sharing, reuse, efficient integration and simplicity. In the absence of

clear service ownership and funding model, ownership may default to today‟s silo

application and product lines.

FAA SWIM: SOA Governance Best Practices – Industry Input (ITAA/GEIA Group)

Page 19

�Consider the example of unifying the user experience across multiple lines of business:

In an optimal SOA-based solution, we create a set of shared services across all

lines of business in support of a uniform user experience, including services that

provide unified access to data.

However, creating such services is not just a technical issue. The lines of business

need to be involved to answer the following types of questions:

Who owns the data and is there agreement to allow the service access to the

data?

How can permission to access the data be obtained?

Who should fund the shared service? Who owns it, or sponsors its

development?

Who‟s responsible to fix it if it breaks?

How is the business going to motivate the separate lines of business to reuse

enterprise assets and shared business services?

Who makes a decision on whether a service can be accessible to other

applications? What happens if potential users of the service disagree on its

content?

Having a well-established service owning and funding model helps resolve such issues

consistently and efficiently. In particular, great care must be given to the data access

needs of future, unintended users.

3.2.4 Task: Identify Success Factors, Enablers and Reuse Motivators

Before considering the success factors and motivators for SOA and service reuse, it is

important to understand the traditional challenges and constraints with shared service

models and reuse.

Lack of agreed upon standards, vendor product/platform interoperability

Semantics for cross-boundary services, service discovery and visibility into

services

Challenges with licensing models in shared services model: Given the

existence of systems using Commercial Off-the-Shelf (COTS) products that

have a pre-established licensing model (for example, per CPU, named-users,

seat-based), exposing existing capabilities as services (or operations) and then

planning „future‟ service consumers has significant cost, legal and

organizational issues that deter service sharing. Such obstacles discourage

interested service providers.

Lack of certification and support: a shared services model historically adds

planning overhead in the areas of availability, reliability and security and do

not guarantee a high quality of service through a certification.

FAA SWIM: SOA Governance Best Practices – Industry Input (ITAA/GEIA Group)

Page 20

�3.2.5 Task: Design Policies and Enforcement Mechanisms

For the successful adoption of SOA, the SOA Governance Model requires complete,

visible support of sponsors and other stakeholders including, but not limited to, the SOA

CoE.

Without adequate checks and balances firmly in place, the foundational processes,

standards and best practices created by the SOA CoE are less likely to be applied in

practice.

Particularly in the early adoption phases of SOA Governance, it is important that regular

vitality checks, walkthroughs, and peer reviews ensure that information and approach

flows smoothly. Governance enforcement requires empowered entities at multiple levels

of enforcement to effectively govern the standards established by the SOA CoE.

The following are some typical and recommended enforcement entities that could have

specific responsibilities attached to them

SOA Steering Committee – strategic and executive guidance of the SOA

journey across the enterprise. This committee ideally should be a

subcommittee of an enterprise level governance committee.

SOA Control Board – tactical guidance on specific tasks performed for the

SOA journey. Again, this should be a part of the enterprise level governance

control board.

SOA CoE (Center of Excellence) Advisory Group – day to day guidance of

the SOA journey.

3.3 Service Management and Monitoring

One of the major common mistakes enterprises make is embarking on SOA by writing

services/Web Services without thinking about service management and monitoring. This

has caused a lot of grief in many organizations. Uncontrollable number of services and

many copies of the same service (duplicate functionality) with only minor variations are

prime examples of lack of service management and monitoring. For this reason, we are

addressing this topic in the service lifecycle. Service management and monitoring should

be considered at Design-Time, not as an afterthought associated solely with IT

operations.

The key to managing services efficiently is to consider them as another resource type.

Services need to be secured, deployed, monitored, versioned, and they should have

formal SLAs (service level agreements) associated with them.

FAA SWIM: SOA Governance Best Practices – Industry Input (ITAA/GEIA Group)

Page 21

�Services introduce additional management challenges emanating from the composite

nature of the solutions they participate in. Challenges around having to manage the

interdependencies among services and maintaining the expected Quality of Service (QoS)

becomes as important as managing the resources that comprise the services themselves.

As stated in section 2, policy management provides a mechanism to allocate IT resources

according to defined policies established by the enterprise. Therefore, in processes,

identification of policy decision points (PDPs), where events are defined and decisions

are made and policy enforcement points (PEPs), where policies are executed and

monitored are essential.

While the underlying technology and standards in support of SOA provide many options

to architect and manage the services, it still takes time and effort to actively design the

management strategy and execute the strategy consistently.

3.3.1 Service Management in the Context of IT Management and

Operations

Figure 3.4 - SOA Solution Abstraction Layers

The above graphic depicts a simplified model of atomic and composite services as

entities and shows the abstract positioning and relationship amongst systems,

components, processes and the consumers.

The intention is to establish the fact that managing services effectively requires

management of the service inter-relationships and dependencies, as well as a support

model that reflects understanding how services relate to each other and to the IT

infrastructure and business process layers.

Flows within the services environment can be controlled through management

mediations such as log, filter, route, and transform. Centralized service management

policies can define how such mediations are applied.

FAA SWIM: SOA Governance Best Practices – Industry Input (ITAA/GEIA Group)

Page 22

�3.3.2 Service Management and Monitoring Tasks

Complete write-up on Service Management and Monitoring is beyond the scope of this

paper. Following is description on two very fundamental tasks that support SOA

governance-related goals.

3.3.2.1 Task: Certification and Publishing of Services

Adding a new „service‟ entity to the set of enterprise assets requires a way to announce its

status and display details to its potential consumers. Service certification and publishing

is a vital process for SOA adoption. One of the biggest advantages of this task is that it

stops arbitrary introduction and deployment of services.

While this is not an entirely new step within IT operations procedures, there are aspects

such as the loosely coupled nature and new interoperability challenges that are distinctly

different from client-server systems and which should be addressed. This is a recognized

area where technology standards and tools (registry, repository etc.) are quickly evolving.

Service certification is a critical part of SOA governance. The main objective of

certifying services is to actively encourage their reuse by warranting overall service

quality and assuring potential new users of the service that it will be fully supported and

appropriate to their needs.

Such service assurance may be achieved through requiring additional accountability

requirements and by publishing the details of such additional certification for the benefit

of potential consumers of the service. Service certification should be carried out under the

control of the Quality Assurance department and should include operational tests that

approximate the actual deployment architecture associated with its initial intended use.

Additional information related to alternative uses, including consumption of the service

over a wide area network if that was not the initial deployment architecture can be

explicitly mentioned, for example.

The certification step builds on the effort already undertaken during the service

identification around reuse and due diligence in identification of potential service

consumers.

Various details that were developed and documented during the service design and

development phase such as SLA and QoS will contribute to the certification process.

Certification formalizes the QA process prior to physically publishing the service as

being „enterprise ready‟, with an assured quality of service and a full and complete set of

support materials.

For example, certification ensures that information such as a version number, ownership,

who is accountable for the service, and that classification and availability of the service

are published as mandatory service metadata.

FAA SWIM: SOA Governance Best Practices – Industry Input (ITAA/GEIA Group)

Page 23

�Certification and publishing services also serve the following purposes:

It helps the IT operations staff capture and document service related metadata.

This benefits visibility and system analysis for later projects that may support

unintended users

During early stages of SOA adoption, it provides a feedback channel from IT

operations to design and development teams. This may result in additional

design time discipline towards services by prompting reuse questions and

considerations associated with the operational aspects of service deployment

The process of certification ensures the correctness of service contracts

created as part of service specification

It establishes the source for communication related to service lifecycle, usage

and subscription information

It demonstrates that the service has adhered to the required sequence of steps

for the service lifecycle status, including intermediate peer reviews. The

purpose of defining formal service statuses and allowed status transitions is to

clearly provide information related to the stage in which the service is at a

given point in time.

The certification review results in a pass or fail status for the service in

consideration. Pass status indicates that the service is ready to be published.

Fail status indicates that further work needs to be done before this can be

certified as a service.

Note: The certification process also applies to services provided by third parties. Third

party arrangements become problematic if the provider changes. Consumer organizations

should establish policies that can cope with a chance in the QoS during initial

negotiations with the provider.

One way to buffer an enterprise from an uncontrolled or volatile change is to hide the

third party service (or services if multiple providers are an option) behind a mediation

layer that then manages external / provider volatility without impacting the core business.

If a service provider changes, the governance processes might include an introspection

of the registry/repository for the mediation "provider" which is under the enterprise’s

control. Any change in service delivery, interfaces, endpoints, etc. would trigger an

announcement to affected consumers.

Some of these requirements might not be established until the service is actually

implemented and Service Level Agreements are negotiated with the Service

Consumers.

3.3.2.2 Task: Versioning Services

Note: Service versioning is an area that has not yet attained practice maturity. Hence, the

context and the guidance below may be considered as leading practices known so far.

FAA SWIM: SOA