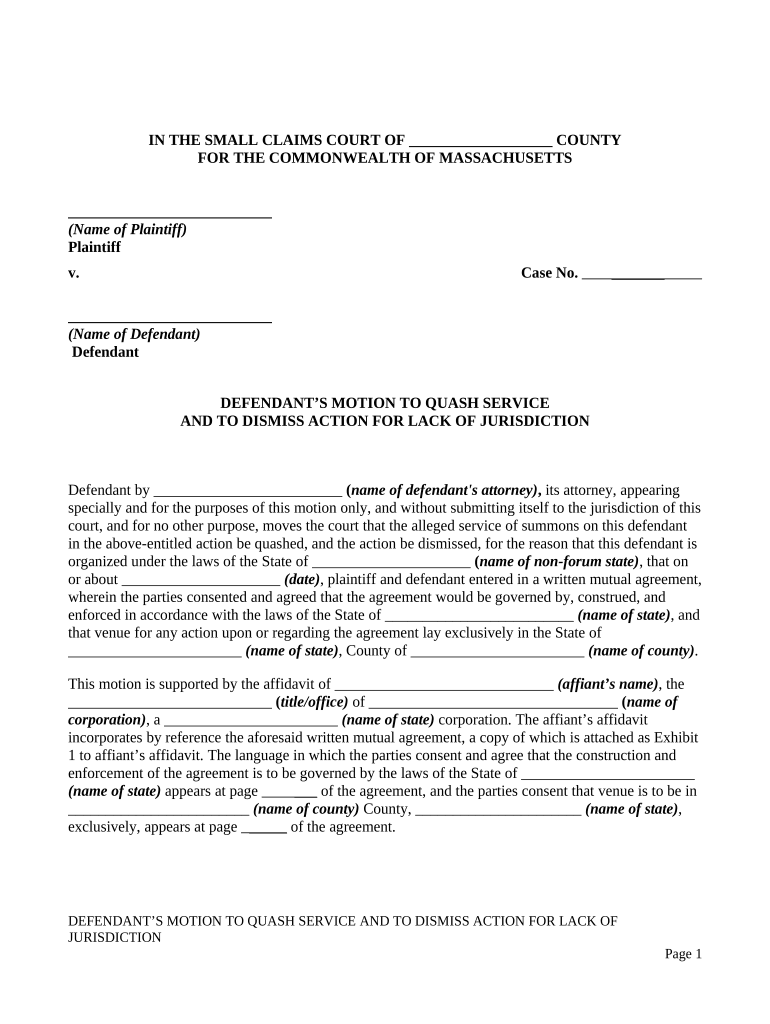

IN THE SMALL CLAIMS COURT OF ___________________ COUNTY

FOR THE COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS

___________________________

(Name of Plaintiff)

Plaintiff

v. Case No. _______

___________________________

(Name of Defendant)

Defendant

DEFENDANT’S MOTION TO QUASH SERVICE

AND TO DISMISS ACTION FOR LACK OF JURISDICTION

Defendant by _________________________ ( name of defendant's attorney) , its attorney, appearing

specially and for the purposes of this motion only, and without submitting itself to the jurisdiction of this

court, and for no other purpose, moves the court that the alleged service of summons on this defendant

in the above-entitled action be quashed, and the action be dismissed, for the reason that this defendant is

organized under the laws of the State of _____________________ ( name of non-forum state) , that on

or about _____________________ (date) , plaintiff and defendant entered in a written mutual agreement,

wherein the parties consented and agreed that the agreement would be governed by, construed, and

enforced in accordance with the laws of the State of _________________________ (name of state) , and

that venue for any action upon or regarding the agreement lay exclusively in the State of

_______________________ (name of state) , County of _______________________ (name of county) .

This motion is supported by the affidavit of _____________________________ (affiant’s name) , the

___________________________ ( title/office) of _________________________________ ( name of

corporation) , a _______________________ (name of state) corporation. The affiant’s affidavit

incorporates by reference the aforesaid written mutual agreement, a copy of which is attached as Exhibit

1 to affiant’s affidavit. The language in which the parties consent and agree that the construction and

enforcement of the agreement is to be governed by the laws of the State of _______________________

(name of state) appears at page ___ of the agreement, and the parties consent that venue is to be in

________________________ (name of county) County, ______________________ (name of state) ,

exclusively, appears at page _____ of the agreement.

DEFENDANT’S MOTION TO QUASH SERVICE AND TO DISMISS ACTION FOR LACK OF

JURISDICTION

Page 1

Dated: , 2______.

Respectfully submitted,

By:

(Name of Defendant’s Attorney)

State Bar No. _____________

Attorney for Defendant

_____________________________

(Name of Defendant’s Attorney)

____________________________________

Address

____________________________________

City, State, Zip Code

Telephone: _______________________

See next page for POINTS AND AUTHORITIES:

DEFENDANT’S MOTION TO QUASH SERVICE AND TO DISMISS ACTION FOR LACK OF

JURISDICTION

Page 2

I. AMJUR APPEARANCE § 2.

Appearances have been classified as either general or special. An appearance is special when the

defendant appears for the purpose of objecting to the jurisdiction of the court over the defendant's

person, and confines the appearance solely to that question of jurisdiction. A general appearance is made

by a party who comes into court and appears in the case in any manner except specially for the specific

purpose of challenging the jurisdiction of the court over the defendant's person. A party may waive its

objection to the erroneous exercise of personal jurisdiction if the party generally appears in the case and

actively prosecutes the action or contests the issues, and, as a general rule, a party's general appearance

will cure any defects in service occurring prior to that time. However, if a judgment has previously been

entered against the defendant, the making of a general appearance does not submit him or her to the

court's jurisdiction retroactively and personal jurisdiction may be challenged.

Personal jurisdiction may be acquired either by the party making a general appearance or by service of

process. Some statutes or rules provide that a defendant's voluntary general appearance is equivalent to

the service of summons upon the defendant. A court's subject matter jurisdiction does not depend on the

conduct or agreement of the parties; and, thus, the parties cannot confer subject matter jurisdiction on a

trial or an appellate court by appearance, plea, consent, silence, or waiver.

A general appearance is entered when a person or the person's attorney comes into court and submits the

party to the jurisdiction of the court. However, filing a notice of special appearance by counsel does not

constitute a waiver of objection to lack of personal jurisdiction.

II. CASE LAW.

KATIE J. LAMARCHE vs. JOHN C. LUSSIER.

65 Mass. App. Ct. 887

September 15, 2005 - April 3, 2006

Present: LENK, DUFFLY, & KATZMANN, JJ.

The defendant in an abuse prevention proceeding did not waive his defense of lack of personal

jurisdiction by appearing at a hearing to extend the protective order, where the defendant had asserted

the defense at the outset of the action and again in multiple objections both in his motions to dismiss and

to continue, as well as during the original hearing. [889-892]

Nothing in the record of an abuse prevention proceeding suggested that any of the grounds for assertion

of personal jurisdiction over the defendant under the Massachusetts long-arm statute.

LENK, J. The defendant, John C. Lussier, appeals from a series of abuse prevention orders entered

against him pursuant to G. L. c. 209A upon the complaint of the plaintiff, Katie J. Lamarche. [Note 1]

On April 13, 2004, Lamarche obtained an ex parte order against the defendant from the Lowell Division

of the District Court Department. At an April 27, 2004, hearing to extend the order, the judge denied the

defendant's motion to dismiss for lack of personal jurisdiction pursuant to Mass.R.Civ.P. 12(b)(2), 365

DEFENDANT’S MOTION TO QUASH SERVICE AND TO DISMISS ACTION FOR LACK OF

JURISDICTION

Page 3

Mass. 755 (1974), and extended the order until July 29, 2004, when, after a hearing, the order was again

extended. We reverse. [Page 888]

1. Background. The plaintiff was born and raised in Massachusetts, where she lived for twenty years,

while Lussier was raised in New Hampshire. The parties had an intimate relationship of about two years'

duration. During that time, in December, 2002, Lamarche moved to New Hampshire to live with the

defendant. A month later, Lussier joined the United States Navy as an intelligence officer and was

stationed in the State of Washington. Lamarche joined Lussier in Washington during the summer of

2003 and bore their son, Adam, [Note 2] on June 27, 2003. [Note 3] She moved back to New Hampshire

briefly in mid-autumn of that year, but then soon returned to Washington. [Note 4] With Adam, she

returned permanently to Massachusetts in April, 2004.

Lamarche's April 13, 2004, affidavit in support of her application for an abuse prevention order recites

that Lussier repeatedly threatened to kill her, warning her that, as an intelligence officer, he could

always discover her whereabouts. She attested that Lussier carried knives, hit her on one occasion,

threatened to hurt Adam, [Note 5] and, during one fight, stabbed and destroyed her cellular telephone.

Lamarche also stated that Lussier had called her mother to tell her that she would never see her daughter

again and should say goodbye. [Note 6] The record suggests that all of these incidents took place while

Lamarche and Lussier were in Washington. Lamarche does not indicate that any communications were

made or received in Massachusetts.

At the April 27, 2004, hearing, Lussier, through counsel, moved both to continue the matter pursuant to

50 U.S.C. App. § 521(d) (Supp. 2005), [Note 7] and to dismiss Lamarche's complaint on the grounds

that personal jurisdiction did not attach. In support of the latter motion, he maintained that since he was

not currently and had never been a resident of Massachusetts, and none of the relevant acts occurred in

Massachusetts, the requirements of G. L. c. 223A, § 3, the Massachusetts long-arm statute, were not

satisfied. The judge allowed the motion to continue; ordered the abuse prevention order continued in

effect until a scheduled July 29, 2004, hearing; and twice denied the motion to dismiss, to which the

defendant twice objected. At the July 29 hearing, the judge continued the order in effect until January

27, 2005; the order indicates that the defendant personally appeared at the hearing.

2. Analysis. A judgment is void if the court from which it issues lacked personal jurisdiction over the

defendant. Colley v. Benson, Young & Downs Ins. Agency, Inc ., 42 Mass. App. Ct. 527 , 532 (1997).

However, "the moving party must show not only a lack of personal jurisdiction, but also that he or she

did not waive the lack of jurisdiction and voluntarily submit to the court's jurisdiction." Id. at 529,

quoting from 12 Moore's Federal Practice § 60.44[3] (3d ed. 1997). The relevant inquiry thus has two

parts: whether there was a waiver and, if there was not, whether there is personal jurisdiction over the

defendant.

a. Waiver. The question before us is whether the defendant waived the personal jurisdiction defense by

appearing at the July 29, 2004, hearing. Such a defense may be waived by conduct, express submission,

or extended inaction. Precision Etchings & Findings, Inc. v. LGP Gem, Ltd ., 953 F.2d 21, 25 (1st Cir.

1992). If a party makes voluntary appearances and contests the case at all stages until judgment is

DEFENDANT’S MOTION TO QUASH SERVICE AND TO DISMISS ACTION FOR LACK OF

JURISDICTION

Page 4

rendered, such conduct gives jurisdiction. Ingersoll v. Ingersoll , 348 Mass. 209 , 210 (1964). [Note 8]

The common factors in a waiver of personal jurisdiction are "dilatoriness and participation in, or

encouragement of, judicial proceedings." Precision Etchings & Findings, Inc. v. LGP Gem, Ltd ., 953

F.2d at 25, quoting from United States to Use of Combustion Sys. Sales, Inc. v. Eastern Metal Prods. &

Fabricators, Inc ., 112 F.R.D. 685, 687 (M.D.N.C. 1986). See Gahm v. Wallace , 206 Mass. 39 , 44-45

(1910) (defendant's assertion of defense other than personal jurisdiction in affidavit indicated intention

to submit to jurisdiction of court); Bishins v. Richard B. Mateer, P.A ., 61 Mass. App. Ct. 423 , 428

(2004) (plaintiffs' voluntary appearance as interveners in Florida court gave that court jurisdiction over

them, and Florida judgment was accorded full faith and credit in Massachusetts).

The threshold question in these cases is whether the defendant brought the jurisdictional defense to the

attention of the court before further proceedings had gotten underway. In Walling v. Beers , 120 Mass.

548 , 550 (1876), the Supreme Judicial Court held that where the defendant appeared specially for the

purpose of contending lack of personal jurisdiction and filed an answer that did not waive the objection

to personal jurisdiction, his acts did not amount to a waiver of that defense. The court noted that "the

objection upon the ground of want of jurisdiction was seasonably taken. There was no formal motion

that the bill should be dismissed, but it is sufficient that, by the form of his appearance, the objection

was brought to the attention of the court. The defendant, by proceeding to trial afterwards, does not lose

the right to say that he did not thereby withdraw his protest against the jurisdiction of the court." Ibid.

See Harkness v. Hyde , 98 U.S. 476, 479 (1879) ("[i]llegality in a proceeding by which jurisdiction is to

be obtained is in no case waived by the appearance of the defendant for the purpose of calling the

attention of the court to such irregularity; nor is the objection waived when being urged it is overruled,

and the defendant is thereby compelled to answer. He is not considered as abandoning his objection

because he does not submit to further proceedings without contestation. It is only where he pleads to the

merits in the first instance, without insisting upon the illegality, that the objection is deemed to be

waived").

While nothing in the record suggests that Lussier raised the jurisdictional defense at the July 29, 2004,

hearing, on several prior occasions he had unmistakably voiced his objections to the court's assertion of

personal jurisdiction. [Note 9] , [Note 10] Our decisions in Vangel v. Martin , 45 Mass. App. Ct. 76

(1998), and Sarin v. Ochsner , 48 Mass. App. Ct. 421 (2000), are not to the contrary. In those cases, we

held that active participation in court proceedings without raising the jurisdictional defense constituted a

waiver. [Note 11] In contrast, Lussier asserted lack of personal jurisdiction at the outset of the action and

again in his multiple objections both in his motions to dismiss and to continue, as well as during the

initial hearing. We cannot say that the court was not "sufficiently informed of the bases of the

defendant's challenges to its jurisdiction . . . ." Morrill v. Tong , 390 Mass. 120 , 125 (1983). Even if

Lussier appeared at the July 29, 2004, hearing without renewing his objections, he had given the court

sufficient notice of his objection to its jurisdiction to preserve the issue for appeal. There was no waiver.

b. Assertion of jurisdiction over the defendant. An assertion of personal jurisdiction over a nonresident

defendant poses a two-pronged inquiry: "(1) is the assertion of jurisdiction authorized by statute, and (2)

if authorized, is the exercise of jurisdiction under State law consistent with basic due process

DEFENDANT’S MOTION TO QUASH SERVICE AND TO DISMISS ACTION FOR LACK OF

JURISDICTION

Page 5

requirements mandated by the United States Constitution?" Good Hope Indus., Inc. v. Ryder Scott Co .,

378 Mass. 1 , 5-6 (1979). The Massachusetts long-arm statute, G. L. c. 223A, § 3, authorizes jurisdiction

to the limits allowed by the Federal Constitution. [Note 12] " Automatic" Sprinkler Corp. of America v.

Seneca Foods Corp. , 361 Mass. 441 , 443 (1972). Even if the facts sustain a claim of personal

jurisdiction under G. L. c. 223A, § 3, the plaintiff must still meet the constitutional requirements of due

process. Good Hope Indus., Inc. v. Ryder Scott Co ., 378 Mass. at 6. REMF Corp. v. Miranda, 60 Mass.

App. Ct. 905 (2004). The plaintiff bears the burden of establishing sufficient facts to assert personal

jurisdiction. Droukas v. Divers Training Academy, Inc ., 375 Mass. 149 , 151 (1978).

Nothing in the record before us suggests that any of the statutory grounds for the assertion of personal

jurisdiction can be satisfied. Lussier lived in the States of New Hampshire and Washington, not in

Massachusetts. There is no suggestion of his having any interest in Massachusetts real property, of his

having transacted any business here, or of his having contracted to supply services or things in

Massachusetts. See G. L. c. 223A, § 3(a), (b), (e). The injuries to Lamarche are asserted to have

occurred while Lamarche and Lussier were living together out-of-State. Although § 3(d) of c. 223A

provides that out-of-State acts can in some circumstances confer jurisdiction, e.g., where the tortious act

caused injury in Massachusetts, there is nothing in the record to indicate that Lamarche engaged in a

"persistent course of conduct" in this State, also a prerequisite to personal jurisdiction under § 3(d). As

Lamarche never maintained a domicil in Massachusetts, and the present claim concerns an abuse

prevention order, rather than matters of domestic relations, § 3(g) does not apply. Last, although the

record shows that a paternity action has been filed in the Probate and Family Court, there is nothing to

indicate that any of the conditions in § 3(h) have been satisfied.

The failure to satisfy the aforesaid requirements of our long-arm statute precludes the need for us to

address whether the activities of the defendant were of sufficient dimension to withstand constitutional

limitations requiring "certain minimum contacts with [the State] such that [jurisdiction] does not offend

'traditional notions of fair play and substantial justice.' " Droukas v. Divers Training Academy, Inc ., 375

Mass. at 152, quoting from International Shoe Co. v. Washington , 326 U.S. 310, 316 (1945).

Notwithstanding the unsavory conduct alleged, it was error for the judge to have concluded that the

requirements for personal jurisdiction had been met and, on this basis, to have denied the defendant's

motion to dismiss.

The G. L. c. 209A orders dated April 13, 2004, through July 29, 2004, are vacated. So ordered.

DEFENDANT’S MOTION TO QUASH SERVICE AND TO DISMISS ACTION FOR LACK OF

JURISDICTION

Page 6