APPLICATION FOR REGISTRATION

NEW MEXICO STATE REGISTER OF CULTURAL PROPERTIES

FORM A

Revised 05/18/07

CONTINUATION SHEET

Section: 15 Page1

______________________________________________________________________________

Geographical Data

Verbal Boundary Description

The Mt. Taylor TCP Boundary: The Intersection of Community Landscapes

The Mount Taylor TCP boundary is defined by the lower slopes of the mesas that enclose

the Mountain’s summit and upper. These land forms include San Mateo Mesa with its associated

extension known as Jesus Mesa, La Jara Mesa, Horace Mesa, and Mesa Chivato with its

associated extension known as Bibo Mesa.

The nomination of Mt. Taylor TCP for permanent listing on the New Mexico State

Register of Cultural Properties, led the Nominating Tribes to revisit the subject of defining the

boundary. With a year to complete the nomination, the Tribes engaged in extended,

collaborative dialogue that was unavailable to them when they nominated Mt. Taylor on the

State Register under the Cultural Properties Review Committee’s (CPRC) emergency provisions.

Their first goal was to find common ground to define a boundary that would acknowledge and

complement the rich tapestry of affiliation that each community culturally and historically

maintains with the Mountain. The Nominating Tribes’ second goal was to apply this collective

understanding of what the Mt. Taylor TCP means to their communities to fulfill the National

Register of Historic Places’ (NRHP) guideline to define the Mountain’s geographic boundary in

terms of their understandings of what it means to their people culturally and historically (Parker

and King 1998:20; see also discussion by Seifert 1997 [1995]:1-2, 27). These goals, proved

challenging because each Tribe possesses a different over-arching conceptual boundary for what

constitutes the Mountain (see discussion by Benedict and Hudson 2008:33).

It is not surprising that each of the five Nominating Tribes possesses a distinctive

understanding of what Mt. Taylor entails as a traditional cultural property. After all, Acoma,

Laguna, Zuni, the Navajo Nation, and the Hopi Tribe are distinctive cultural communities.

Ethnography, ethnohistory, history, and archaeology show collectively that each Nominating

Tribe traces a unique record of cultural-historical experience. In turn, contemporary landscape

investigators recognize that landscapes are the products of carefully maintained culturalhistorical experience. For example, Mt. Taylor represents a different Mountain of Cardinal

Direction among the four Nominating Tribes who are its closest neighbors: Acoma (north),

Laguna (west), Zuni (east), and Navajo Nation (south). The Hopi Tribe, in addition to viewing

Mt. Taylor as its Mountain of the Northeast, provides yet another dimension of contrast because

it considers this landform as a prominent landscape feature relied upon by some of its clans

during their migration to the Hopi Mesas, not unlike a beacon.

�APPLICATION FOR REGISTRATION

NEW MEXICO STATE REGISTER OF CULTURAL PROPERTIES

FORM A

Revised 05/18/07

CONTINUATION SHEET

Section: 15 Page2

______________________________________________________________________________

Diverse opinions about what Mt. Taylor is and why it is important also exist within each

of the Tribes. Different social groups, such as clans and ceremonial societies, in each Tribal

community maintain distinctive relationships with Mt. Taylor and its landscape features.

Therefore, individual members of the same Nominating Tribe comprehend Mt. Taylor as existing

in relationship with cultural-historical events and places that can be different from other

individual members of the same Tribe. For example, among the Navajo, people collectively

have opined that their understanding of Mt. Taylor included references to Cabezon Peak in the

Rio Puerco Valley (of the East), Grants Mesa on the northeast limits of the City of Grants, and

Flower Mountain, between the Pueblos of Acoma and Laguna southeast of Mt. Taylor.

Individual community members might not mention all three places, however.

The cultural diversity embodied in the Mt. Taylor TCP as defined by the five Nominating

Tribes is not just an imposing challenge, it is also a strength. As Figure 15.1 illustrates

schematically, the Mount Taylor TCP is the cultural landscape created at the intersection of the

five Nominating Tribes’ generalized community landscapes. As such, it has layers upon layers

of traditional cultural meaning and affiliation that is a common bond uniting the Nominating

Tribes and the many different social groups that exist with each of the communities. For the

Nominating Tribes (as well as for countless peoples representing a multitude of communities

throughout the region), Mt. Taylor is one of those truly exceptional places that people talk about

with passion and conviction (after Ortiz 1992:321–324).

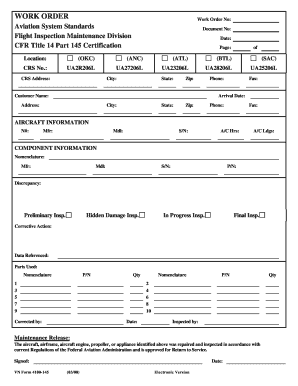

Figure 15.1

�APPLICATION FOR REGISTRATION

NEW MEXICO STATE REGISTER OF CULTURAL PROPERTIES

FORM A

Revised 05/18/07

CONTINUATION SHEET

Section: 15 Page3

______________________________________________________________________________

Verbal Boundary Justification

Mt. Taylor TCP Boundary Definition and Justification

Although the statement that the TCP exists at the intersection of the Nominating Tribe’s

community landscapes is a valuable observation relevant to the issues of the Mountain’s

significance and integrity (see below), it still does not explain where the TCP is and what it

encompassesCareful consideration of the pushes and pulls originating within and among the

Nominating Tribes in their efforts to define the Mt. Taylor TCP boundary proved to be a time

consuming task. The Nominating Tribes were able to reach consensus through two findings

reported in the U.S. Forest Service’s determination that the Mt. Taylor TCP is eligible for listing

on the National Register of Historic Places. First,

All the tribes consulted [the Pueblos of Acoma, Laguna, Zuni, Jemez, Isleta, the

Hopi tribe, the Jicarilla Apache Nation, and the Navajo Nation] agree that a large

boundary [which extends from Mt. Taylor’s preeminent summit, down the

Mountain’s slopes and across San Mateo Mesa, Jesus Mesa, La Jara Mesa,

Horace Mesa, and Mesa Chivato to the bases of their slopes] is more appropriate.

[Benedict and Hudson 2008:33]

Second,

All the tribes involved in consultation regarding Mt. Taylor indicated that as a

cultural use area and spiritual landmark, the TCP (site) in its entirety is important.

The mesas extending from the peak in all directions are culturally significant.

Trails traverse the mesas, and shrines, springs, places of offerings, and other

cultural sites are found on and around the mesas. Specific information provided

by the tribes varied by mesa, but all agreed that these mesas have been used, and

continue to be used for a variety of traditional cultural and religious activities.

[2008:33, punctuation in original]

Having embraced these principles to guide their efforts, the Tribes realized that the

boundary identified in their Emergency Nomination was inadequate. The initial boundary was

set at the 8,000-foot elevation to include Mt. Taylor’s summit and the portions of most mesas at

elevations of 8,000 feet or higher for the entire TCP. The one exception consisted of a lower

elevation to the 7,300-foot contour to include Horace Mesa at the southwest corner. (Sanchez et al.

2008). By not extending the boundary to the bases of all of the mesas, the Tribes had not fulfilled

the NRHP’s guidance for defining the TCP’s boundary in terms of their collective understandings

�APPLICATION FOR REGISTRATION

NEW MEXICO STATE REGISTER OF CULTURAL PROPERTIES

FORM A

Revised 05/18/07

CONTINUATION SHEET

Section: 15 Page4

______________________________________________________________________________

about what the Mountain comprises geographically and what it means to their people in terms of

their culture and history. In view of this shortcoming, the Nominating Tribes had not vigilantly

considered their traditional uses of Mt. Taylor (see Parker and King 1998:20). The Tribes’ ready

decision to include Horace Mesa in the Emergency Nomination due to its prominence in their

cultural-historical memories and lives, anticipated the U.S. Forest Service’s subsequent findings

following their completion of comprehensive consultations with the Nominating Tribes and other

affiliated tribal communities, however.

To delineate the Mt. Taylor TCP in terms of their common conceptual understandings of

the Mountain and the diverse traditional uses of this landscape, the Nominating Tribes concluded

that the boundary set by the U.S. Forest Service (Benedict and Hudson 2008) was an astute

analysis of the information that U.S. Forest Service staff had gathered through their respective

tribal consultations. For example, Laguna and Acoma conceive of the Mountain as encompassing

their communities and people generally, but there is an inner boundary at the base of the mesas

defined by guardian peaks, the volcanic necks that surround the mountain just outside the

designated boundary. (See, Significance Statement of Laguna in at Section Two(C) in

Continuation Sheet12). At the same time, these peaks are just outside Zuni’s concept of the

north and east boundaries of the Mountain. Among the Navajo, however, the concept of the

Mountain did not include the communities of Acoma and Laguna. The dilemma that confronted

the Nominating Tribes in their effort to set a boundary for what the Mountain is and where it is

geographically is answered by the guardian peaks.

The location of these Guardians supports the Tribes’ general acceptance of the U.S.

Forest Service TCP boundary for their own purposes. The guardian summits, standing just

beyond the bases of the enclosing mesas, look back (and watch over) the Mountain’s summit,

upper slopes, and surrounding mesas. This distinctive core area, which is a geographically

coherent landscape feature, is also the innermost sanctum of each Tribe’s concept of the

Mountain. In bounding the heart of the Mountain in terms of the bases of San Mateo Mesa,

Jesus Mesa, La Jara Mesa, Horace Mesa, and Mesa Chivato, including the extension referred to

as Bibo Mesa (see figure L-4 reproduced below), the Nominating Tribes have cast themselves in

roles resembling those of Laguna and Acoma’s guardians summits; the Tribes seek to protect the

Mountain’s heart.

�APPLICATION FOR REGISTRATION

NEW MEXICO STATE REGISTER OF CULTURAL PROPERTIES

FORM A

Revised 05/18/07

CONTINUATION SHEET

Section: 15 Page5

______________________________________________________________________________

Figure L-1. Guardian Peaks in relation to the boundary of the Mount Taylor traditional cultural

property recognized by the Cibola National Forest.

The Nominating Tribes’ justify including San Mateo Mesa, Jesus Mesa, La Jara Mesa,

Horace Mesa, and Mesa Chivato within the boundary of the Mt. Taylor TCP for the same

reasons previously put forward by the U.S. Forest Service in its Determination of Eligibility (after

Benedict and Hudson 2008:34-35):

San Mateo Mesa, including Jesus Mesa

The Pueblo of Acoma recalls that their community members went to San Mateo Mesa to

harvest the ponderosa pine timbers used in the construction of the renowned San Esteban del Rey

Mission in the mid-seventeenth century. The Indian Claims Commission proceedings also

documented that Acoma’s herdsmen have used extensive parts of the mesa as sheep pasturage

during the previous century.

�APPLICATION FOR REGISTRATION

NEW MEXICO STATE REGISTER OF CULTURAL PROPERTIES

FORM A

Revised 05/18/07

CONTINUATION SHEET

Section: 15 Page6

______________________________________________________________________________

The Pueblo of Laguna states that its people still visit the San Mateo and Jesus mesas for

gathering piñon nuts and other plant products, and for hunting wild game. In the early twentieth

century, Laguna sheep herders used to drive livestock through this area to graze at homesteads

located along Inditos Draw.

The Pueblo of Zuni reports that its various societies make trips to the mesas to collect

plants, minerals, and sand used in ceremonial observances conducted for the community’s

welfare. There are also shrines, places of blessing and offering, and ceremonial trails whose

locations are strictly privileged information

Among the Navajo, the San Mateo and Jesus mesas in combination represent “a footprint

of the deities” (Benedict and Hudson 2008:34). The characterization of these mesas as a

“footprint” follows from the traditional understanding that supernatural beings, referred to as the

“Holy People,” use the San Mateo and Jesus mesas as one of their principal corridors on their

travels among the Navajo’s Mountains of Cardinal Direction.

La Jara Mesa

The Pueblo of Acoma views La Jara Mesa, in its entirety, as an essential landscape feature

due to its importance during some of the ancestors’ migrations in search for Haaku. The mesa

abounds with a variety of contributing cultural properties, which are actively used today but whose

locations, names, and purposes are such highly privileged information that details cannot be

disclosed. The fact that Acoma joined with the Pueblo of Zuni and the Hopi Tribe, in 2000 to

select a place in La Jara Mesa’s vicinity for the reburial of people whose remains were uncovered

during excavations of a nearby Ancestral Puebloan village, illustrates the continuing great sanctity

of this landform today. The Pueblo of Acoma also ran flocks of sheep in the mesa’s higher

elevations during the prior century, and the people continue to identify La Jara Mesa as a favored

location for gathering piñon nuts.

The Pueblo of Laguna states that its community members use La Jara Mesa for gathering

piñon nuts and other plant products, and for hunting wild game.

Just as Zuni Pueblo stated for San Mateo Mesa, societies from the Pueblo visit La Jara

Mesa to collect plants, minerals, and sand used in ceremonial observances. There are also

shrines, places of blessing and offering, and ceremonial trails on La Jara Mesa whose locations

are confidential.

For the Navajo, La Jara Mesa is the “breast portion” (Benedict and Hudson 2008:34) of

the body of One Walking Giant (a.k.a. Monster Giant), who was slain by Twin Sons, Born for

�APPLICATION FOR REGISTRATION

NEW MEXICO STATE REGISTER OF CULTURAL PROPERTIES

FORM A

Revised 05/18/07

CONTINUATION SHEET

Section: 15 Page7

______________________________________________________________________________

Water and Monster Slayer (a.k.a. Enemy Slayer). La Jara Mesa is equally important in Navajo

culture as a place for gathering medicinal plants and grazing sheep.

Horace Mesa

As the favored location for the proposed Enchanted Skies Observatory and Park, the

affiliations that each of the Nominating Tribes maintain with Horace Mesa are well documented

(Anyon 2001; Polk 1997; also, see Benedict and Hudson 2008:34). The Pueblo of Acoma still

identifies the breath of the mesa as a principal pathway for pilgrimages to Mount Taylor’s summit

and as a favored location for collecting piñon and locating obsidian for use in traditional practices.

Places of blessing and offering are numerous, as are springs, which enclose the landform’s upper

and lower elevations. Because springs represent not only precious water sources, but also portals

of communication with the supernatural realm of the cosmos to maintain the flow of water in the

natural world, the importance of the springs on Horace Mesa (and elsewhere within the Mt. Taylor

TCP) to Acoma’s culture cannot be overlooked. In the recent past, Acoma shepherds ran flocks

across the mesa’s higher reaches. Horace Mesa also occupies a prominent place in the

community’s traditional history of its origins, most particularly through references to a

supernatural being who lit fires all over this mesa specifically (and the Mountain in general) to

enhance the earth’s fertility.

The Pueblo of Laguna continues to use pilgrimage pathways, numerous shrines, places of

blessing and offering, piñon collection and other plant gathering loci, and sacred springs, as well as

tracts for hunting game animals. Laguna sheep herders used to graze livestock on Horace Mesa

until the mid-twentieth century.

The Navajo Nation similarly recognizes pilgrimage pathways, numerous places of blessing

and offering, piñon collection and other plant gathering loci, and springs, as well as tracts for

hunting game animals. The Navajo also maintain that there are grave sites “all over” the mesa top,

and it figures notably in traditional accounts of Navajo origins which took place in the distant past

as well as comparatively recent cultural manifestations and tribal history alike.

Bow Priests, the Łe’wekwe (Sword Swallower Society), Newekwe (Galaxy Society), and

Make’lhanna:kwe (Big Fire Society), and Kiva Groups from the Pueblo of Zuni have shrines,

blessing and offering areas, springs, and ceremonial trails located on Horace Mesa. In addition,

specific plants and minerals employed in healing and ceremonial activities are collected from

this landscape feature. The Zuni also view the archaeological sites located on Horace Mesa as

verification of Zuni origins and migration history, and as validation of their rightful role within

this landscape.

�APPLICATION FOR REGISTRATION

NEW MEXICO STATE REGISTER OF CULTURAL PROPERTIES

FORM A

Revised 05/18/07

CONTINUATION SHEET

Section: 15 Page8

______________________________________________________________________________

The Hopi Tribe maintains that some of its clans occupied Horace Mesa during their

migrations to the Hopi Mesas. The Hopi continue to visit this mesa on pilgrimages that

commemorate and reenact these movements, as well as to collect plants and minerals from the

Mountain for use in rites back in their communities (Anyon 2001, in Benedict and Hudson

2008:34).

Mesa Chivato, including Bibo Mesa

The Pueblo of Acoma’s identifications of La Cueva Grande, which is in Cañon Juan

Tafoya (a.k.a. Marquez Canyon), and Cañon Juan Tafoya as a whole as significant landscape

features along the northeast boundary of its traditional core homeland (Bibo 1952) are but two

examples of the community’s ties with Mesa Chivato. This expansive landform is additionally

important given the numerous near-permanent springs and lakes (Figure 15.3) that are of great

importance to Acoma, just as the other four Nominating Tribes. Also important to Acoma are

ancestral Puebloan archaeological sites, and several other important shrines and boundary markers,

including Cerro Chivato and Cerrito Zorrillo.

Figure 15.3

�APPLICATION FOR REGISTRATION

NEW MEXICO STATE REGISTER OF CULTURAL PROPERTIES

FORM A

Revised 05/18/07

CONTINUATION SHEET

Section: 15 Page9

______________________________________________________________________________

Mesa Chivato is an important cultural area for the Pueblo of Laguna. There are many

important shrines and sacred springs in this area, which people from Laguna visit during

pilgrimages to Mt. Taylor. The area is also important for collecting plants, hunting, and grazing

livestock.

Bow Priests, the Łe’wekwe (Sword Swallower Society), Newekwe (Galaxy Society), and

Make’lhanna:kwe (Big Fire Society), and Kiva Groups from the Pueblo of Zuni have shrines,

blessing and offering areas, springs, permanent water sources, water ways, and ceremonial trails

located on Mesa Chivato. In addition, specific plants and minerals employed in healing and

ceremonial activities are collected from across this broad landform. The Zuni also view the

archaeological sites located on Mesa Chivato as verification of Zuni origins and migration

history, and as validation of their rightful role within this landscape. There are also historic Zuni

trails that cross Mesa Chivato connecting the Pueblo of Zuni with Bandelier, the Sandia

Mountains, Chaco Canyon, and Mesa Verde.

U.S. Forest Service staff previously summarized the breadth of relationships that the

Navajo Nation and the Hopi Tribe maintain with Mesa Chivato:

It is known from past consultation on federal undertakings that the portion of

Chivato Mesa…previously identified as the “checkerboard area” is heavily used,

particularly by the Navajo, for [the] gathering of piñon nuts and a variety of cultural

activities (U.S. Forest Service 2000b, 2007). In 1999, the Diné Medicine Man

Association identified an historic fire/smoke signaling site that was used when the

Utes were raiding the area (Benedict 1999). Another location of significant cultural

values was identified by the Canoncito Band of Navajo during a series of fieldtrips

and meetings in 1999. The area is important in their on-going cultural practices; it

is the location for a named ceremony, a place where offerings are left, minerals are

collected for use in sand painting and in puberty ceremonies, and plant gathering

occurs (particularly tobacco.) Hopi oral traditions indicate that Hopi clans occupied

or migrated through this area on their ways to the Hopi Mesas. [Benedict and

Hudson 2008:34-35]

Mt. Taylor TCP Boundary Modifications and Private Property Exclusions

Before concluding the discussion of the Mt. Taylor TCP boundary, a description of the

ways in which the Nominating Tribes depart from the Forest Service’s border definition, is

warranted. One set of modifications includes three small-scale adjustments to the Forest Service’s

boundary in recognition of either the Nominating Tribes’ understandings of the Mountain in

general or their acknowledgement of their specific historical patterns of affiliation with the

�APPLICATION FOR REGISTRATION

NEW MEXICO STATE REGISTER OF CULTURAL PROPERTIES

FORM A

Revised 05/18/07

CONTINUATION SHEET

Section: 15 Page10

______________________________________________________________________________

Mountain. The second group of changes concerns the exclusion of all private property holdings

within the Mt. Taylor TCP boundary.

Concerning the first set of boundary modifications, the five Nominating Tribes presenting

this application are a subset of the tribes that the Forest Service actively consulted when deciding

on a boundary. (see Benedict and Hudson 2008:13-14). The boundary defined for this nomination

for permanently listing Mt. Taylor on the State Register differs in three localized details. First, the

Nominating Tribes slightly extended the northeast boundary of the TCP to enclose the lower slopes

of the summit known as Bear Mouth. Second, the boundary south of the present-day community

of San Mateo is slightly upslope to accurately portray their patterns of land use and active

affiliation, taking into consideration San Mateo’s development since the 1950s. Third, the Tribes

reworked the TCP’s south boundary to follow the Cubero Land Grant boundary. They made this

adjustment to acknowledge Acoma Pueblo’s long-standing relationship with the existence of the

Cubero Land Grant and the changes to Acoma’s specific historical patterns of affiliation in the

Cubero area as a result of the Pueblo’s coexistence with the Land Grant. Importantly, all three of

these adjustments comply with the National Register Bulletin 38 guideline to vigilantly consider

their traditional uses of Mt. Taylor (see Parker and King 1998:20).

In addition to the minor geographic boundary adjustments, the Nominating Tribes

explicitly exclude all privately owned parcels within the Mt. Taylor TCP’s geographic border as

noncontributing resources of the property. To satisfy the NRHP’s guideline to delineate a

geographic boundary for the TCP in terms of what the Mountain means to their people culturally

and historically, the Nominating Tribes necessarily defined a tract whose limits crosscut a myriad

of landownership types, including private holdings, as well as federal, tribal, state, and land grant

holdings. In its Determination of Eligibility, the U.S. Forest Service noted,

The concept of having a boundary that crosses multiple land jurisdictions should be

viewed in the same manner it is when the Forest encounters an archaeological site

that straddles the boundary between Forest land and private land. The portion of

the site on National Forest land is documented. When it is known that the site

continues onto private land, but access to the portion on private land is denied, the

Forest Service extends the mapped boundary of the site onto private land to

acknowledge its presence, and to reflect what is known about the extent of the site

on private land. [Benedict and Hudson 2008]

The NRHP applies similar logic in its guidelines for documenting archaeological sites

specifically and cultural properties generally. For example, the NRHP notes that for

archaeological sites that cross onto private property, “The SPHO or other nomination sponsor

would be expected to make every effort to identify the totality of the property prior to nomination,

so that the nomination reflects the entire resource” (Little et al. 1997 [1995]:56). Moreover, the

�APPLICATION FOR REGISTRATION

NEW MEXICO STATE REGISTER OF CULTURAL PROPERTIES

FORM A

Revised 05/18/07

CONTINUATION SHEET

Section: 15 Page11

______________________________________________________________________________

NRHP process suggests the use of legal boundaries to define cultural boundaries (Little et al. 1997

[1995]:56).

NRHP’s procedural protocols specifically support the Nominating Tribes’ cultural logic in

the decision to exclude all private property holdings as noncontributing resources of the property

within the boundary of the Mt. Taylor TCP in other significant ways. First, the NRHP directs a

nomination’s sponsor to “encompass the resources [i.e., in the present case, the mesas and their

lower slopes surrounding Mt. Taylor’s summit and upper slopes] that contribute to the property’s

significance” (Seifert 1997 [1995]:1). In other words, the NRHP process stipulates that the Tribes

define the limits of eligible resources. Second, although the NRHP recognizes that cultural

property’s boundaries “may also have legal and management implications,” it is careful to state

that the NRHP process “does not limit the private owner’s use of the property. Private property

owners can do anything they wish with their property, provided no federal license, permit, or

funding is involved” (Seifert 1997 [1995]:1). Finally, in reference to the discussion of the

exclusion of noncontributing resources, the NRHP guidelines contain the directive that when

noncontributing areas are comparatively

small and surrounded by eligible resources, they may not be excluded, but are

included as noncontributing resources of the property. That is, do not select

boundaries which exclude a small noncontributing island surrounded by

contributing resources; simply identify the noncontributing resources and include

them within the boundaries of the property. [Seifert 1997 (1995):2]

�