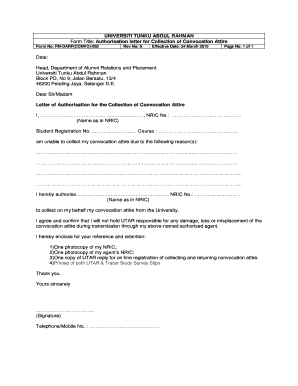

Benson Snippets:

Digitized Copies of

Books from Latin

American Collection

Appear Online

by

María Elena González Marinas

I

In January 2007, the University of Texas

Google’s Goals: Online Discovery of Book Contents

Libraries signed a cooperative agreement with

Google to digitize no fewer than one million books

from its collections over the next six years. By summer 2008, Google had digitized more than 300,000

volumes from the unique holdings of the Benson

Latin American Collection and made available online digital copies of

many of the photographs, illustrations, maps, graphs, and charts as

well as the text of two to three hundred of these books. Titles from the

Benson that appeared online include such forgotten classics as Paul

Groussac’s El viaje intelectual and a rare account by Argentine Navy

officer Jose M. Sobral of his exploration of Antarctica, Dos años entre

los hielos, 1901–1903.

Through the parallel efforts of Google Library Partners in the United

States and Europe, Latin Americanists everywhere in the world will

soon have online keyword, author, title, publisher, or publication date

access to the full text of tens of thousands of rare and out-of-print

books from the finest research collections.

One of four large-scale digitization projects under way in the United

States, the Google Library Partners now includes twenty-eight research

libraries with total holdings in the hundreds of millions of books.

The combined holdings from the libraries of the original five Google

partners—Harvard, Michigan, New York Public Library, Oxford, and

Stanford—have been estimated at 58 million volumes. Of these, 15

million are planned to be digitized and online within ten years. Other

mass-digitization initiatives include the Carnegie Mellon University’s

Million Book Project, Microsoft’s Live Search Books, and the well publicized Open Content Alliance.

Google’s main goals are to make the contents of books discoverable

by as wide an audience as possible and ultimately help authors and

publishers sell more books. Google has the resources, the indexing

capacity, the search engine, and so far the incentive to digitize, instantaneously sort through, and disseminate the millions of bytes that the

imaged books are taking up on the Google servers. Since many of the

books take up an average of 20 megabytes each, the first lot of 15 million will absorb a minimum of 300 terabytes of server space. This is

about four times the bytes the Library of Congress estimates the U.S.

National Digital Information Infrastructure and Preservation Program

has processed to date.

Like all other initiatives to digitize and make gargantuan masses of

materials available online, Google is restricted by copyright law. A web

of international copyright laws protects recently published books as

well as many obscure, hard-to-find, and out-of-print books, precluding their dissemination online. To accommodate legal restrictions,

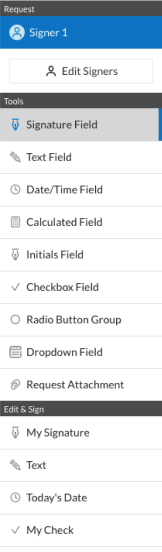

Google developed a three-tiered system for delivering desired texts

to users as Snippets, in Limited View, or in Full View. That is, when

searched in Google Book Search, texts protected by copyright appear

as phrases on a fortune cookie, separated from essential bibliographic

information including pagination; these are called Snippets. At most,

the Snippet returns a few lines of text before and after the keyword

or phrase entered by the user.

When permission is granted by the copyright owner—often the

publisher of a book—Google more liberally displays as much as

50–75 percent of the book. If a book is clearly in the public domain,

then the book appears in full text ready for downloading by the user

llilas

portal

40

�as a document file. In some cases, there is

no preview of the book at all but basic bibliographic information is provided including

author, title, publisher, date of publication,

number of pages. When the holder of a text

is one of the library partners, the name of the

library is identified. Additional links in the

“About This Book” section of the Google Book

Search results guide the reader to the libraries

nearest them that also have the book in their

collections. Google directs readers interested in

purchasing books to links to publishers, online

vendors, and used book dealers.

Google earns revenues from publishers

willing to pay for each reader clicking on the

publishers’ Web sites and by selling links to

nonpublisher sites related to the book’s contents; so far, these last are few and appear

unobtrusively as footers in the Google Book

Search results page. Although revenue figures related to publisher site visits have been

impossible to tally from public records, Google

claims to have agreements with more than

10,000 publishers. As long as these agreements

are profitable, Google Book Search revenues

remain relatively secure and unprofitable clicks

to library Web sites will likely continue to be

subsidized.

Inevitable Controversy

Controversy about the Google initiative broke

out shortly after the first Library Partner pilot

projects were announced in 2004. Complaints

revolved around two key points: Google

intended not only to scan and add to their

databases the entire contents of all partner

library books—whether or not protected by

copyright—but also to index the material. Commercial publishers and university presses sued

on grounds that the scanning of copyrighted

texts as well as the proprietary indexing by

Google went beyond fair use and thus violated

the rights of copyright holders. In turn, Google

proposed an opt-out program for publishers

and authors who did not want their works digitized or publicized by Google. It should be very

clear, however, that Google never intended to

make public the full text or even parts of text

of materials protected by copyright. Although

the case has not been resolved, substantive

arguments as to whether the use of text snippets or image thumbnails falls under the fair

use provisions outlined by U.S. copyright law

have taken on new dimensions as lawsuits

unrelated to research and teaching purposes

Like all other initiatives to

digitize and make gargantuan

masses of materials available

online, Google is restricted

by copyright law.

To accommodate legal

restrictions, Google developed a three-tiered system for

delivering desired texts to

users as Snippets, in Limited

View, or in Full View.

make their way through the courts.

Fearing Google as a colossal advertising

mechanism as well as a popular search engine,

many suspect that it will likely be the enterprise to implement a yet-to-be devised business

model to exploit the scholarly texts commercially. If that turns out to be the case, no one

can determine the long-term consequences of

trusting Google to control such a vast collection of research material. Competitors are also

concerned about Google’s incomparable capital

resources and power to squelch innovation in

the mining of large digital collections. For a

specialized bibliography that traces speculation about the impactof the Google initiative

on publishing and research patterns, one may

refer to Google Book Search by former University of Houston librarian Charles W. Bailey,

Jr. See http://www.digital-scholarship.org/

gbsb/gbsb.htm

llilas

portal

41

On the other hand, anxiety about the likelihood that Google will abandon the Google

Library Partnerships before reaching its stated

goals peaked in May 2008 when Microsoft

announced that it would end similar massdigitization projects, Live Search Books and

Live Search Academic Services. By that date,

Microsoft and its partners had digitized threequarter million books and tens of millions of

scholarly journal articles. Microsoft turned

over the digital files to Ingram Digital, which

already had functioned as the host for the

Microsoft Live Search Books files. Presumably,

publishers will now have to renegotiate terms

with Ingram or opt out of the project.

Less concerned about business practices,

some scholars fear that popular mass digitization programs will reduce the motivation

of research libraries to preserve the original copies. Others question the rationale for

�imaging millions of printed pages at a time that

scholars demand massive data sets they can

manipulate. To date, mapping, notation, and

data aggregation tools provided by Google have

proven inadequate for scholarly use.

individual works, with the intent of uncovering

the maximum number of titles in the public

domain. Books in the public domain may be

presented online in full view and prepared

for downloading by anyone with adequate

technology.

Library Partner Goals

Many research libraries, including the Library

of Congress, have undertaken ambitious book

digitization programs but not on this scale.

Given the limited resources and lack of access

to the necessary technology, individual research

libraries have not been able to digitize more

than a few thousand of their books, confirming

librarians’ estimates that digitization of their

holdings would take generations to complete.

Google’s proposal to digitize and service the

digital archive of their collections at no cost

to the research libraries not only accelerated

the rate at which the digitization processes can

take place, but it promises to quickly multiply

the number of printed books to be digitized

from the thousands to the millions.

Alliance with Google assures research

libraries that their books will be more easily

discovered by users worldwide and their collections made known beyond the walls of an

institution. These outcomes advance the mission

of universities to disseminate knowledge and

fulfill the mandate of libraries to expand and

diversify access services. Librarians are beginning to accept digital copies as an important

means of preserving their collections much as

they once did microfilm reproductions of books

and manuscripts so that partnering with Google

has been repeatedly justified as an affordable

long-term preservation strategy. The creation

of digital copies for preservation is defensible

as a fair use and is sensible as a solution to

replacement for lost and fragile items.

Several research libraries, such as those

at the University of Michigan and Stanford

University, also have leveraged these largescale projects to develop user-oriented search

applications and improve the integration of

disparate digital collections. In connection with

the Google Library Partnership, the University

of Texas Libraries staff is testing the means to

link the corresponding digitized texts to the

main online catalog author entries.

In addition, research staff began an investigation of copyright laws in various Latin

American countries and joined colleagues at

the University of Michigan in refining procedures for determining the copyright status of

Copyright Laws in Latin America

The global distribution of potential readers

and authors complicates the determination

of the copyright status of individual works

disseminated online. Although the language

of current copyright laws flows from that of

the Berne Convention and is harmonized

through multilateral treaties among countries, definitions and duration of copyright

protection vary widely from country to country.

The laws of individual countries distinguish

authored works, anonymous and pseudonymous works, edited works, and translations

as well as works-for-hire, among others, while

copyright protection terms vary from fifty to

one hundred years, sometimes calculated from

the date of publication for compiled works or

from the year of death for authored works. In

the case of multiple authors, copyright protection is calculated from the year of death of the

last living author.

The classification of creative works, the

identification of authors, the accurate determination of author death, and the correct

calculation of the duration of copyright are

complex, time-consuming, and painstaking

tasks. They are also risky, as errors could prove

embarrassing, if not expensive. Consequently,

the rules for determining the copyright status

of large numbers of books must be extremely

conservative. That is the case with Google’s

algorithms.

According to the U.S. law, books published

anywhere before 1923 are no longer protected

in the United States and are categorically in

the public domain. After that date, a series of

conditions related to copyright formalities,

trade agreements, treaties, and court decisions

must be conjugated in order to arrive at the

copyright status of a work. Ironically, at different times U.S. law has provided copyright

protection beyond the term the works enjoyed

in the country of origin. Many of the books

in the Benson Latin American Collection are

works that had been in the public domain in

the country of origin but were republished

with a new foreword, annotations, or similar

editorial additions, thus making it difficult to

llilas

portal

42

separate the original text for dissemination

throughout the digital public domain. Edited

and republished works make up a substantial

portion of research libraries like the Benson

Latin American Collection, which increased

book purchases and exchanges during the

1960s. All of the republished work will be

protected by copyright law for many more

years and will continue to appear to the Google

Book Searcher as Snippets.

Creative Uses of Google Book Search

Although small-scale and mass digitization

projects have been recognized as a boon to

classicists, Medieval, Renaissance, and Early

Modern scholars in general, Latin Americanists

have not had enough time to use the newly

available materials and to publicize their experiences accessing and utilizing mass digital

libraries. Recent postings on discussion lists

and formal publications by historians, print

history, and book culture scholars in general

have been mostly negative, creating additional

doubt about the value of the endeavor. The

more positive comments admit to the usefulness of mechanisms that allow user-chosen

searches over millions of books and recognize

Google Book Search as an effective finding

aid for pinpointing the location of arcane

and regional materials currently scattered

worldwide without having to consult foreign

language union catalogs.

Because the books that are being digitized

come off the shelves as raw inventory from

dozens of research libraries, few attempts have

been made to select or curate subcollections

in relation to the interest or research needs of

faculty and students. Indeed, the individual

researcher must carefully select from a huge

mass of digitized titles for their personalized collections. It will be up to researchers

to prompt their home institutions to assist

in those searches and to provide the tools to

restructure the contents within the digitized

books so that they can be analyzed and manipulated as a mass—of snippets.

Explore Google Books Search, http://books.

google.com/advanced_book_search and have

a say on what will be done next!

María Elena González Marinas is Assistant

Professor in the Library and Information Science

Program at Wayne State University. She received

her Ph.D. from the School of Information at the

University of Texas at Austin. ✹

�