Land Use Policy 28 (2011) 185–192

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Land Use Policy

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/landusepol

Is Oregon’s land use planning program conserving forest and farm land?

A review of the evidence

Hannah Gosnell a,∗ , Jeffrey D. Kline b,1 , Garrett Chrostek c,2 , James Duncan a

a

Department of Geosciences, Oregon State University, Wilkinson 104, Corvallis, OR 97331-5506, USA

Pacific Northwest Research Station, USDA Forest Service, 3200 SW Jefferson Way, Corvallis, OR 97331, USA

c

Department of Political Science, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331, USA

b

a r t i c l e

i n f o

Article history:

Received 7 July 2009

Received in revised form 22 March 2010

Accepted 27 May 2010

Keywords:

Land use planning

Oregon

Farmland protection

Forest land protection

Evaluation methodology

Land use change

a b s t r a c t

Planners have long been interested in understanding ways in which land use planning approaches play out

on the ground and planning scholars have approached the task of evaluating such effects using a variety

of methods. Oregon, in particular, has been the focus of numerous studies owing to its early-adopted

and widely recognized statewide approach to farm and forest land protection and recent experiment

with relaxation of that approach in 2004 with the passage of ballot Measure 37. In this paper we review

research-based evidence regarding the forest and farm land conservation effects of Oregon land use

planning. We document the evolution of methods used in evaluating state land use planning program

performance, including trend analysis, indicator analysis, empirical models, and analysis of indirect effects

on the economic viability of forestry and farming. We also draw on data documenting Measure 37 claims

to consider the degree to which Measure 37 might have altered land use and development trends had

its impacts not been tempered by a subsequent ballot measure – Measure 49. Finally, we provide a

synthesis of the current state of knowledge and suggest opportunities for future research. Common to

nearly all of the studies we reviewed was an acknowledgement of the difficulty in establishing causal

relationships between land use planning and land use change given the many exogenous and endogenous

factors involved. Despite these difficulties, we conclude that sufficient evidence does exist to suggest that

Oregon’s land use planning program is contributing a measurable degree of protection to forest and farm

land in the state.

© 2010 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Introduction

A variety of public policies and programs are advocated in the

U.S. to protect forest and farm lands from development. These

include zoning, use value assessment, purchasing or transferring

development rights, and purchasing conservation easements or

land in fee, to name a few. Among these, Oregon’s land use planning program often is cited in both professional and popular media

as exemplary (e.g., Nelson, 1992; Egan, 1996). A central goal of the

program is to protect productive farm and forest land sufficient

to safeguard the industries those lands support, and, secondarily, because they are a widely recognized contributor to Oregon’s

∗ Corresponding author. Tel.: +1 541 737 1222; fax: +1 541 737 1200.

E-mail addresses: gosnellh@geo.oregonstate.edu (H. Gosnell), jkline@fs.fed.us

(J.D. Kline), chrosteg@onid.orst.edu (G. Chrostek), duncanj@geo.oregonstate.edu

(J. Duncan).

1

Tel.: +1 541 750 7250; fax: +1 541 750 7329.

2

Tel.: +1 541 737 2811; fax: +1 541 737 2289.

0264-8377/$ – see front matter © 2010 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2010.05.012

overall quality of life. The extent to which Oregon’s land use planning program is effectively accomplishing its forest and farm land

conservation goals, however, is a subject of debate among both

citizens and scholars. Given that most of the debates have been

about “how to plan, not whether to plan” (Abbot et al., 2003, p. 390),

there have been numerous attempts to assess the effectiveness of

Oregon’sparticular approach.

Oregon’s land use planning program was launched in 1973.

Between 1973 and 2001, privately owned “wildland” forest

declined from 10.7 to 10.5 million acres, while intensive agriculture declined from 5.8 to 5.7 million acres (Lettman, 2002, 2004).

Today, forest lands and intensive agriculture make up 37% and

20% of the nonfederal land base in Oregon, respectively. Additional acreage exists as mixed forest and agriculture as well as

range. Would there have been greater loss and fragmentation of

these resource lands over the past 35 years under a more lax or

different land conservation program? In this paper we report on

a review of research addressing the effects of Oregon’s land use

planning program on rates and patterns of forest and farm land

development and fragmentation (or parcelization). We document

�186

H. Gosnell et al. / Land Use Policy 28 (2011) 185–192

the evolution of methods used in evaluating state land use planning

program performance, including trend analysis, indicator analysis,

and empirical models. We also consider the degree to which recent

attempts to change Oregon’s land use planning program via ballot

Measure 37 might have altered land use and development trends

had the impacts not been tempered by a subsequent ballot measure

– Measure 49. Finally, we provide a synthesis of key findings and

outline our thoughts about how research might best be applied to

advance knowledge and application of statewide planning to forest

and farm land conservation.

Relatively few studies have examined the performance and

effects of land use planning and fewer still have provided confident

conclusions. One of the biggest challenges confronting this type of

research is separating the effects of land use planning on land cover

change from other influential factors. These factors can include

population and economic growth; new industries; regional comparative advantages of land in different uses; changes in household

sizes, personal income, and tastes and preferences regarding housing; the availability of land for re-development; and physical land

features, such as slope, that constrain certain uses, among others

(Kline, 2000). In Oregon, evaluative research is further complicated

by the evolving nature of the State’s program, which has experienced periodic changes in laws and policies to correct perceived

problems. These structural changes add complexity to obtaining

and analyzing longitudinal data as policy changes and sampling

periods rarely align. Given these challenges, our review does not

seek to quantify the success of Oregon land use planning or provide a definitive answer as to its overall effectiveness. Rather, it

summarizes the research evidence, identifies knowledge gaps, and

draws tentative conclusions based on the evidence at hand. Our

hope is that this critical analysis of methods used to date and the

limitations of conclusions drawn will help planners and policymakers consider and evaluate land use planning approaches to forest

and farm land conservation and their effects in other states.

Oregon’s land use planning program

Oregon’s land use planning program has been cited as a pioneer in U.S. land use policy for its statewide scope (Gustafson et

al., 1982), has won national acclaim by the American Planning

Association (Department of Land Conservation and Development

[DLCD] 1997), and has served as a model for statewide planning in

other states (Abbott et al., 1994). The program was a response to

rapid population growth in western Oregon during the 1950s and

1960s, which raised concerns in the state about the loss of forests

and farm land to development. Legislation had already authorized

local governments to manage urban growth, however, residential development of forests and farm lands outside of incorporated

cities often remained unplanned and unregulated (Gustafson et al.,

1982). In response, Oregon’s legislature enacted the Land Conservation and Development Act in 1973 requiring all cities and counties

to prepare comprehensive land use plans consistent with several

statewide goals and establishing the Land Conservation and Development Commission to oversee the program (Knapp and Nelson,

1992; Abbott et al., 1994).

Among several goals of the program are the orderly and efficient

transition of rural lands to urban uses, the protection of forests and

agricultural lands, and the protection and conservation of natural

resources, scenic and historic areas, and open spaces (DLCD, 2004c,

p. 1). To pursue these goals, cities and counties are required to focus

new development within urban growth boundaries, and restrict

development outside of urban growth boundaries by zoning those

lands for exclusive farm use, forest use, or as exception areas (Pease,

1994). Exception areas are unincorporated rural areas where low-

density residential, commercial, and industrial uses prevail, and

where development is allowed, pending approval by local authorities (Einsweiler and Howe, 1994). Exceptions are granted when

strict adherence to a particular goal is not possible or not in the

public interest, or when adherence to one goal may conflict with

another.

Land use planning does not prevent development, but rather

restricts the rates, locations, and densities at which development

can take place. Some development within forest and farm use

zones can be approved by local authorities and must be reported

to the Land Conservation and Development Commission (Land

Conservation and Development Commission [LCDC] 1996a,b). Criteria defining such development vary across counties, but generally

include minimum parcel sizes and limits on the number of new

dwelling permits issued. Construction of personal residences by

commercial farmers and forest owners is allowed, subject to an

income test designed to discourage recreational/hobby uses of farm

and forest land. Though the land use planning system was initiated in 1973, it was not until 1986 that comprehensive plans for all

36 counties and 241 cities in the state were acknowledged by the

Land Conservation and Development Commission (Knapp, 1994).

This lag time complicates efforts to assess the performance of the

system going back to 1973.

Although Oregon’s planning program has enjoyed general legislative and citizen support, since its inception it has created

tension between its advocates who see land use planning as necessary to the long-term conservation of forest and farm lands, and

its detractors who argue that land use regulations unduly burden

private landowners (Oppenheimer, 2004a,b). Among the biggest

complaints are that it is too prescriptive and inflexible, that it

unfairly impinges on private property rights, and it does not reflect

a changed economic and social environment since its adoption 35

years ago (Abbot et al., 2003; Howe et al., 2004). Moreover, Howe

(1994) suggests that the Oregon program, while innovative, does

not have a mechanism for critically engaging new ideas. As a result,

people become frustrated with what seems to be overwhelming

program inertia (p. 281).

Two fairly recent ballot measures seeking to provide private

landowners compensation for property value losses resulting from

the program exemplify the persistent tension surrounding the program. Measure 7 was approved by voters in 2000 and eventually

was overturned by the Oregon Supreme Court on a technicality

(DLCD, 2004a). Measure 37 was approved in 2004 also seeking

compensation, and would have allowed planning jurisdictions to

remove, modify, or not apply the regulation in lieu of compensation

(DLCD, 2004b). The potential implications of Measure 37 were of

sufficient concern to state policymakers that the governor and state

legislature appointed the bipartisan “Big Look” task force to examine the land use planning program and consider possible changes.

Measure 37 also inspired yet another ballot measure – Measure 49

passed by voters in 2007 – which sought to both define and restrict

compensation eligibility requirements mandated under Measure

37. These issues continue to evolve today. Also persistent is interest

among land use planners and policymakers (in Oregon and elsewhere) in evaluating the effectiveness of planning for maintaining

resource lands.

Literature review method

In our review we focused on published research evaluating the

forest and farm land conservation effects of Oregon’s land use planning program. Although the program has several goals, we limited

our review to research addressing either or both of the goals related

to the conservation of farm and forest land – Goals 3 and 4, respec-

�H. Gosnell et al. / Land Use Policy 28 (2011) 185–192

tively. We refrained from including research that has examined

planning-related secondary effects, such as the potential impacts of

planning on property values. Although such secondary effects have

garnered significant interest over the years among planners, policymakers, and landowners, they are not central to the primary goals

defined at the program’s outset – specifically, the conservation of

productive forest and farm lands.

Potential research literature was identified using keyword

searches of various databases and evaluated for its relevance to

addressing the question of whether and how Oregon’s land use

planning program has effected farm and forest land conservation in

the state. We limited our review to studies published between 1973

and 2008; including peer-reviewed journal articles and reports by

state and federal agencies. After meeting initial criteria pertaining to relevance; studies were subsequently evaluated for their

robustness. Robustness depended on whether the analysis was

structured in such a way as to enable assessing the degree to

which land use planning effected forest and farm land conservation apart from other contributing factors influencing the loss of

forest and farm land to development. For example, could an analysis distinguish changes in rates and patterns of forest and farm

land development resulting from land use planning from changes

resulting from other factors such as population and income growth;

topography; and broader market forces affecting forestry and

farming?

Results

Our review identified three broad classes of studies that represent an evolution in methods used to evaluate forest and farm

land conservation effects of land use planning in Oregon. Initial

pioneering efforts focused on examining general trends in land use

– usually agricultural land – using readily available data sources

such as the US Census of Agriculture. The majority of the studies we cite fall into this category. A subsequent group of studies

attempted to develop indicators regarding the effect of land use

planning on forest and farm land development. Common to both

types of research, we suggest, is an inability to effectively control for

other factors besides planning that influence land use change and

development. A third class of more recent studies built upon these

earlier efforts by using more intensively sampled data describing

land use to construct empirical models of land use change. These

studies more explicitly attempted to control for at least some of the

other factors that influence land use change and development.

Analyses of land use trends

Several studies have examined historical trends in various land

use categories or in specific development metrics, to assess farm

and forest land loss (conversion to development), as well as fragmentation (parcelization). While the growing number of small farm

and forest properties – at the expense of larger operations – may

not signify an immediate net loss of resource land there has been

concern that parcelization in the longer term lead to greater costs

for farm and foresy operations and thus the decline of farming

and forestry. This concern arises in part from studies suggesting

that parcelization of lands adjacent to working farms and forests,

often for hobby uses, will eventually lead to what some have called

“shadow conversion,” where the growing financial (and psychological) costs of doing business in such a non-production-oriented

atmosphere outweigh any economic benefits (e.g., Sorensen et al.,

1997; Kline and Alig, 2005). Related to this is the concern that the

growing “rent gap” – the difference between what landowners can

earn from forestry or farming versus what they could earn by selling

187

land for development – eventually induces some farm and forest

landowners to sell out.

The earliest studies of Oregon land use planning effectiveness

examined trends in farm land loss and fragmentation using data

from the Census of Agriculture. Furuseth (1981) examined trends in

agricultural land use reported through 1978 by the Census of Agriculture, concluding that a slowing in the rate of agricultural land

loss – plus agricultural land expansion in some areas – provided

empirical evidence of the early effects of Oregon’s land use planning

program. However, given that actual development and implementation of county plans largely occurred after 1978 (after the period

analyzed), these conclusions must be considered suspect. Moreover, drawing such conclusions by observing trends alone can be

a difficult task confounded by other factors that also effect land

use trends. In this case, for example, it would have been difficult

to isolate the potential effects of Oregon land use planning on agricultural land use trends from other factors, such as the expansion

of U.S. agriculture generally that occurred during the early 1970s.

Later comparative analysis by Daniels and Nelson (1986) using the

1982 Census of Agriculture concluded that Oregon was retaining

farm land better than national averages, having lost only 1.7% of

its farm land between 1978 and 1982 versus 3% for the nation. The

authors also found that Oregon had lost less farm land (1978–1982)

than did Washington, a comparable state without statewide land

use planning at that time.

Daniels and Nelson (1986) were also among the first to examine the parcelization phenomenon on resource lands in Oregon

and found that between 1978 and 1982 the state ranked fifth in

the nation in the percentage increase in small farms (64

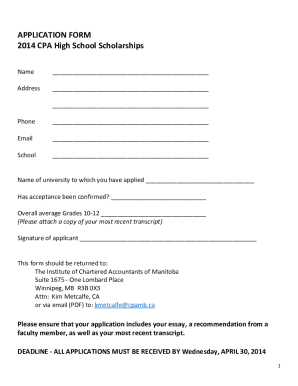

With land use planning

Forest

−99,756

Agriculture

−322,403

Mixed

−59,571

45,477

174,384

16,557

54,279

148,019

43,014

−481,730

236,418

245,312

314,672

780,368

76,544

121,027

314,514

95,597

Total

Without land use planning

Forest

−435,699

Agriculture

−1,094,882

Mixed

−172,141

Total

−1,702,722

1,171,584

531,138

Differenceb

Forest

Agriculture

Mixed

335,943

772,479

112,570

−269,195

−605,984

−59,987

−66,748

−166,495

−52,583

Total

1,220,992

−935,166

−285,826

a

b

Estimated using the econometric model described in Kline (2005a,b).

The “with” figure minus the “without” figure.

not intended to stop development nor did it do so. Rather, urban

growth boundaries have always been intended to accommodate

20 years worth of new development; and, since their inception,

development within those bounds has continued. Some of that

development likely would have taken place without planning,

largely because of its proximity to existing urban areas. What proportion of those lands addressed by Measure 37 claims might also

have been developed in the absence of planning remains unknown.

Discussion and further research needs

Despite the significant interest in Oregon’s land use planning

program since its inception and the rather large body of research

focused on weighing its effectiveness, little empirical analysis

exists that has rigorously analyzed the forest and farm land conservation effects of the program. Many studies tend to be descriptive

in nature, focusing on land use trends since land use planning

was implemented, or comparing general land use indicators across

various states or regions, for example. Although these descriptive

analyses provide a story of shifting land use trends coinciding with

the evolution of Oregon’s land use planning program, the failure to

control for the numerous socioeconomic and topographic factors

that influence land use change and development confound their

ability to draw meaningful conclusions about the potential causal

relationships between zoning and rates and patterns of forest and

farm land loss. Analyses based on econometric models arguably

have gone the farthest in attempting to control for at least some

of these factors, however imperfectly. The overall impression that

emerges from these analyses is that Oregon’s land use planning

program has resulted in a measurable, if also incremental, degree

of protection of forest and farm land since its full implementation

in the mid-1980s.

Whether Oregon land use planning has resulted in significant

conservation of forest and farm land sufficient to declare the program a success is a question that will elicit different responses from

different observers. Some observers will see relatively little forest and farm land protected, while others will be more satisfied

with the current situation. Recent data from the Census of Agriculture indicate that farmland acres continue to decline in the state,

from 17.7 million acres in 1997 to 16.4 million acres in 2007 (US

Bureau of Census, 2009). The extent to which land use planning

has translated into sustained or improved farming and forestry

viability remains somewhat uncertain as well, since merely protecting farm and forest land does not guarantee the continuation

of commercial farming and forestry on those lands. Much has been

written, for example, about the ways in which the large minimum

lot sizes associated with Oregon’s land use planning system may

inadvertently encourage the growth of hobby farming, potentially

at the expense of commercial farming. This body of literature may

warrant a separate review.

In weighing the evidence to date, we must remember that Oregon land use planning was not intended to stop development,

but rather to facilitate the orderly and efficient development of

rural lands while protecting forest and farm lands (Knapp and

Nelson, 1992; Abbott et al., 1994). Realizing measurable conservation effects from land use planning is likely a slow process involving

incremental changes in land use patterns over long periods of time.

Land use planners, policymakers, and the public must gauge the

effectiveness of planning programs over decades rather than years,

and work towards a shared understanding of what might have happened in planning’s absence, and a shared vision of desired future

conditions.

Future research can assist in that process if existing data

resources and analytical avenues are used effectively. The following

are what we see as the most promising and needed next steps:

• Greater spatial tracking and evaluation of forest and farm land

lost to development to better differentiate between planned and

unplanned loss, both within and outside of urban growth boundaries. Such analyses could take advantage of existing spatial

data sets (e.g. Lettman, 2002, 2004) or initiate spatial analyses

of lesser-used sources such as the Natural Resources Inventory.

Such analyses should focus on isolating land use planning effects

from socioeconomic, topographic, and other factors that also

influence land use change and development.

• Greater tracking and evaluation of the quality of forest and farm

land lost to development, based on soils and other topographic

information. An important aspect of Goals 3 and 4 is the maintenance of forestry and farming viability. In this respect the quality

of land is important; however it has not received much attention

in past research literature. Enright et al. (2002) initiated such an

effort by tabulating acreage within different soil classes both outside and within urban growth boundaries, but they did not track

changes over time.

• Greater use of spatial land use data to examine both the effects of

development on forestry and farming viability, and related mitigation effects resulting from land use planning. Existing forestry

and farming viability studies are a first step in examining the

influence of development on forestry and farming. However,

future studies must try to link viability measures more directly

to development and land use planning. One recent (unpublished)

study by a University of Washington graduate student used a

promising new method to test whether the approval and sitting of dwellings in Hood River County led to decreased resource

land activity on adjacent lands (Veka, 2008). Using aerial photos

to locate dwellings on resource lands, Veka classified the surrounding resource uses and documented how resource use had

changed between 1994 and 2005. Results showed there were

no significant differences in either resource use or land conversions between areas where higher numbers of dwellings were

approved on resource lands and areas where fewer numbers of

dwellings were approved. In fact, there were instances where

dwellings approved for resource use led to more intensive (activities requiring more investment) resource use on surrounding

lands. Although this study was not statistically robust according to our review criteria, land use planners are interested in

�H. Gosnell et al. / Land Use Policy 28 (2011) 185–192

the potential for applying this method in other parts of the

state.

• Analyses of the ways in which Oregon’s land use planning program has influenced quality-of-life factors through its forest

and farm land conservation effects. Most research evaluating the effectiveness of Oregon’s approach has focused on

maintenance of the commercial aspects of forestry and farming. The program, however, likely provides other significant

benefits associated with the enhancement of water quality, scenic views, and other environmental amenities, which

are also important to Oregonians and could even encourage continued in-migration to the state. The extent to which

Oregon land use planning has met these more latent objectives or has led to greater in-migration largely remains

unknown.

Conclusion

The existing body of research evaluating the forest and farm

land conservation effects of Oregon’s land use planning program

suggests that the Program has resulted in a measurable degree of

forest and farm land protection since its inception in 1973. Land

use planning, however, is a complex multifaceted approach to forest and farm land conservation which seeks to influence rates

and patterns of land use change and development through zoning and permitting processes. Its effects are largely incremental,

occur over long periods of time, and are therefore difficult to measure especially in light of the many confounding factors that also

influence land use change and development. For these reasons,

planners and policymakers are cautioned to carefully consider both

stated and unstated caveats that might or might not accompany

any analysis of planning conservation effects. The body of research

evaluating the forest and farm land conservation effects of Oregon land use planning represents an evolution of approaches and

methods ranging from analysis of land use trends and development indicators to the use of more complex empirical techniques

that attempt to account for factors other than planning that also

influence land use change and development. Even so, there is significant room for continued evolution and continued refinement.

In many respects, existing research regarding the forest and farm

land conservation effectiveness of planning has only scratched the

surface in terms of data and techniques used, leaving a variety of

opportunities available for future scholars interested in examining program effectiveness in Oregon and elsewhere and comparing

that effectiveness to other forest and farm land conservation

approaches.

References

Abbot, C., Adler, S., Howe, D., 2003. A quiet counterrevolution in land use regulation:

the origins and impact of Oregon’s Measure 7. Housing Policy Debate 14 (3),

383–425.

Abbott, C., Howe, D., Adler, S., 1994. Introduction. In: Abbott, C., Howe, D., Adler, S.

(Eds.), Planning the Oregon Way. Oregon State University Press, Corvallis, OR, p.

328.

Bernhardt, L.D., 1988. The growth of non-commercial farming in Oregon’s

Willamette Valley: assessing impact on commercial agriculture. M.Sc. thesis,

Oregon State University.

Daniels, T.L., 1986. Hobby farming in America: rural development or threat to commercial agriculture? Journal of Rural Studies 2 (1), 31–40.

Daniels, T.L., Nelson, A.C., 1986. Is Oregon’s farm land preservation program working? Journal of the American Planning Association 52 (1), 22–32.

Department of Land Conservation and Development [DLCD], 1997. Shaping Oregon’s future: biennial report for 1995–97 from Oregon’s Department of Land

Conservation and Development to the Sixty-ninth Legislative Assembly. Oregon

Department of Land Conservation and Development, Salem, OR.

Department of Land Conservation and Development [DLCD], 2004a. History of

the program. Salem, OR. http://www.oregon.gov/LCD/history.shtml (accessed

25.03.05).

191

Department of Land Conservation and Development [DLCD], 2004b. Measure 37 information, Salem, OR. http://www.oregon.gov/LCD/measure37.shtml

(accessed 25.03.05).

Department of Land Conservation and Development (DLCD), 2004c. Oregon’s

statewide planning goals and guidelines. Oregon Department of Land Conservation and Development, Salem, Oregon. http://www.lcd.state.or.us/goalhtml/

goals.html (accessed 25.03.05).

Egan, T., 1996. Drawing a hard line against urban sprawl. The New York Times, December 30, section A, p. 1, column 2.

Einsweiler, R.C., Howe, D.A., 1994. Managing ‘the land between’: a rural development paradigm. In: Abbott, C., Howe, D., Adler, S. (Eds.), Planning the Oregon

Way. Oregon State University Press, Corvallis, OR, p. 328p.

Enright, C., Hulse, D., Richey, D., 2002. Soils. In: Hulse, D., Gregory, S., Baker, J. (Eds.),

Willamette basin planning atlas, 2nd ed. Oregon State University Press, Corvallis,

OR.

Furuseth, O.J., 1981. Update on Oregon’s agricultural protection program: a land use

perspective. Natural Resources Journal 21, 57.

Gustafson, G.C., Daniels, T.L., Shirack, R.P., 1982. The Oregon land use act: implications for farm land and open space protection. Journal of the American Planning

Association 48 (3), 365–373.

Howe, D., 1994. A research agenda for Oregon planning: problems and practice for

the 1990s. In: Abbot, C., Howe, D., Adler, S. (Eds.), Planning the Oregon Way.

Oregon State University Press, Corvallis, OR, p. p.328.

Howe, D., Abbot, C., Adler, S., 2004. What’s on the horizon for Oregon planners?

Journal of the American Planning Association 70 (4), 391–397.

Institute of Portland Metropolitan Studies, 2006. Mapping Measure 37. Portland

State University, 9p. http://www.pdx.edu/ims/measure-37-database-maps

(accessed 2.12.09).

Kline, J.D., 2000. Comparing states with and without growth management analysis based on indicators with policy implications, comment. Land Use Policy 17,

349–355.

Kline, J.D., 2005a. Forest and farm land conservation effects of Oregon’s (USA) landuse planning program. Environmental Management 35 (4), 368–380.

Kline, J.D., 2005b. Predicted future forest- and farm land development in Western

Oregon with and without land use zoning in effect. Res. Note PNW-RN-548. U.S.

Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station,

Portland, OR.

Kline, J.D., Alig, R.J., 1999. Does land use planning slow the conversion of forest and

farm lands? Growth and Change 30 (1), 3–22.

Kline, J.D., Alig, R.J., 2005. Forestland development and private forestry with examples from Oregon (USA). Forest Policy and Economics 7, 709–720.

Knapp, G., 1994. Land use politics in Oregon. In: Abbott, C., Howe, D., Adler, S. (Eds.),

Planning the Oregon Way. Oregon State University Press, Corvallis, OR, p. 328.

Knapp, G., Nelson, A.C., 1992. The Regulated Landscape: Lessons on State Land Use

Planning from Oregon. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, Cambridge, MA, 243 p.

Land Conservation and Development Committee (LCDC), 1996a. Exclusive Farm Use

Report, 1994–1995. Oregon Department of Land Conservation and Development, Salem, OR, 87p.

Land Conservation and Development Committee (LCDC), 1996b. Forest use report,

1994–1995. Oregon Department of Land Conservation and Development, Salem,

OR.

Lettman, G.J. (coordinator), 2002. Land use change on non-federal land in western

Oregon 1973–2000. Oregon Department of Forestry, Salem, OR.

Lettman, G.J. (coordinator), 2004. Land use change on non-federal land in eastern

Oregon 1975–2001. Oregon Department of Forestry, Salem, OR.

Moore, T., Nelson, A.C., 1994. Lessons for effective urban-containment and resourceland- preservation policy. Journal of Urban Planning and Development 120 (4),

157–171.

Nelson, A.C., 1992. Preserving prime farm land in the face of urbanization: lessons

from Oregon. Journal of the American Planning Association 58, 467–488.

Nelson, A.C., 1999. Comparing states with and without growth management analysis

based on indicators with policy implications. Land Use Policy 16 (2), 121–127.

Nelson, A.C., Moore, T., 1996. Assessing growth management policy implementation: case study of the United States’ leading growth management state. Land

Use Policy 13 (4), 241–259.

Oppenheimer, L, 2004a. Initiative reprises land battle. Portland Oregonian,

September 20, http://www.oregonlive.com/printer/printer.ssf?/base/news/

1095681480156700.xml (accessed 25.03.05).

Oppenheimer, L. 2004b. The people: landowners take sides on Measure 37. Portland Oregonian, October 7. http://www.oregonlive.com/printer/printer.ssf?/

base/news/109715027827560.xml (accessed 25.03.05).

Pease, J.R., 1994. Oregon rural land use: policy and practices. In: Abbot, C., Howe,

D., Adler, S. (Eds.), Planning the Oregon Way. Oregon State University Press,

Corvallis, OR, p. 328.

Sorensen, A.A., Greene, R.P., Russ, K., 1997. Farming on the Edge. American Farmland

Trust, Center for Agriculture and the Environment, Northern Illinois University,

DeKalb, IL, 29p.

US Bureau of Census, U.S., 2009. 2007 Cenus of Agriculture. Department of Commerce, Washington, DC.

Veka, C.H., 2008. An Evaluation of the Impact of Dwellings on Land in Farm and Forest Zones in Hood River County, Oregon. MS Thesis. University of Washington,

Seattle, WA.

Wu, J., Cho, S.H., 2007. The effect of local land use regulations on urban development

in the western United States. Regional Science and Urban Economics 37 (1),

69–86.

�192

H. Gosnell et al. / Land Use Policy 28 (2011) 185–192

Further reading

Kline, J.D., Azuma, D.L., 2007. Evaluating forest land development effects on private

forestry in eastern Oregon. Res. Pap. PNW-RP-572. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station, Portland, OR, 18p.

Kline, J.D., Azuma, D.L., Alig, R.J., 2004. Population growth, urban expansion, and

private forestry in western Oregon. Forest Science 50 (1), 33–43.

Nelson, A.C., 1988. An empirical note on how regional urban containment policy

influences interaction between greenbelt and exurban land markets. Journal of

the American Planning Association 54 (2), 178–184.

Oregon Board of Agriculture, 2007. The State of Oregon Agriculture, 2007. Biennial

Report to the Governor and Legislative Assembly. Salem, OR.

�