© 2016 - U.S. Legal Forms, Inc

USLegal Guide to

Defamation; Libel and

Slander

I NTRODUCTION

The law of defamation

protects a person’s

reputation and good

name against

communications that are

false and derogatory.

Defamation consists of

two torts: libel and

slander. Libel consists of

any defamation that can

be seen, most typically

in writing. Slander

consists of an oral

defamatory

communications. The

elements of libel and

slander are nearly

identical to one another.

Historically, the law

governing slander

focused on oral

statements that were

demeaning to others. By

the 1500s, English

courts treated slander

actions as those for

damages. Libel

developed differently,

however. English

printers were required to

be licensed by and give

a bond to the

government because the

printed word was believed to be a threat to

political stability. Libel

included any criticism of

the English government,

and a person who

committed libel

committed a crime. This

history carried over in

part to the United States,

where Congress under

the presidency of John

Adams passed the

Sedition Act, which

made it a crime to

criticize the government.

Congress and the courts

eventually abandoned

this approach to libel,

and the law of libel is

now focuses on recovery

of damages in civil

cases.

Beginning with the

landmark decision in

New York Times v.

Sullivan (1964), the U.S.

Supreme Court has

recognized that the law

of defamation has a

constitutional

dimension. Under this

case and subsequent

cases, the Court has

balanced individual

interests in reputation

with the interests of free

speech among society.

This approach has

altered the rules

governing libel and

slander, especially

where a communication

is about a public official

or figure, or where the

communication is about a matter of public

concern.

P ROVING D EFAMATION

Defamation is an act of

communication that

causes someone to be

shamed, ridiculed, held

in contempt, lowered in

the estimation of the

community, or to lose

employment status or

earnings or otherwise

suffer a damaged

reputation. Such

defamation is couched in

'defamatory language'.

Libel and slander are

subcategories of

defamation. Defamation

is primarily covered

under state law, but is

subject to First

Amendment guarantees

of free speech. The

scope of constitutional

protection extends to

statements of opinion on

matters of public

concern that do not

contain or imply a

provable factual

assertion.

In order to prove

defamation, the plaintiff

must prove:

■that a statement was

made about the

plaintiff’s reputation,

honesty or integrity that

is not true;

■publication to a third

party (i.e., another

person hears or reads the

statement); and

■the plaintiff suffers

damages as a result of

the statement.

Examples of defamatory

statements are virtually

limitless and may

include any of the

following:

■The communication

that imputes a serious

crime involving moral

turpitude or a felony

■A communication that

exposes a plaintiff to

hatred

■A communication that

reflects negatively on

the plaintiff’s character,

morality, or integrity

■A communication that

impairs the plaintiff’s

financial well-being

■A communication that

suggests that the

plaintiff suffers from a

physical or mental

defect that would cause

others to refrain from

associating with the

plaintiff.

One question with which

courts have struggled is

how to determine which

standard should govern

whether a statement is

defamatory. Many

statements may be

viewed as defamatory by

some individuals, but

the same statement may

not be viewed as defamatory by others. In

some instances, the

context of a statement

may determine whether

the statement is

defamatory. The

Restatement provides as

follows: “The meaning

of a communication is

that which the recipient

correctly, or mistakenly

but reasonably,

understands that it was

intended to express.”

Courts generally will

take into account

extrinsic facts and

circumstances in

determining the meaning

of the statement. Thus,

even where two

statements are identical

in their words, one may

be defamatory while the

other is not, depending

on the context of the

statements.

In a defamation action,

the recipient of a

communication must

understand that the

defendant intended to

refer to the plaintiff in

the communication.

Even where the recipient

mistakenly believes that

a communication refers

to the plaintiff, this

belief, so long as it is

reasonable, is sufficient.

It is not necessary that

the communication refer

to the plaintiff by name.

A defendant may

publish defamatory material in the form of a

story or novel that

apparently refers only to

fictitious characters,

where a reasonable

person would

understand that a

particular character

actually refers to the

plaintiff. This is true

even if the author states

that he or she intends for

the work to be fictional.

In some circumstances,

an author who publishes

defamatory matter about

a group or class of

persons may be liable to

an individual member of

the group or class. This

may occur when: (1) the

communication refers to

a group or class so small

that a reader or listener

can reasonably

understand that the

matter refers to the

plaintiff; and (2) the

reader or listener can

reasonably conclude that

the communication

refers to the individual

based on the

circumstances of the

publication.

Generally, courts require

a plaintiff to prove that

he or she has been

defamed in the eyes of

the community or within

a defined group within

the community. Juries

usually decide this

question.

Defamation is a difficult

wrong to prove, as there

are various factors that

are to be taken into

consideration. The court

must evaluate the

defendant’s

investigation, or lack

there of, concerning the

accuracy of the

statement. How

thoroughly the

investigation was

handled will reflect upon

the nature and interest of

the person who

communicated the

statement. Generally,

defamation damages

will not be awarded if

the defendant had an

honest but yet mistaken

belief in the truth of the

statement. The amount

of damages that can be

awarded is a matter of

subjective determination

for the court, based on

all the facts and

circumstances in each

case.

Another requirement in

libel and slander cases is

that the defendant must

have published

defamatory information

about the plaintiff.

Publication certainly

includes traditional

forms, such as

communications

included in books,

newspapers, and

magazines, but it also includes oral remarks.

So long as the person to

whom a statement has

been communicated can

understand the meaning

of the statement, courts

will generally find that

the statement has been

published. F AULT

At common law, once a

plaintiff proved that a

statement was

defamatory, the court

presumed that the

statement was false. The

rules did not require that

the defendant know that

the statement was false

or defamatory in nature.

The only requirement

was that the defendant

must have intentionally

or negligently published

the information.

In New York Times v.

Sullivan, the Supreme

Court recognized that

the strict liability rules

in defamation cases

would lead to

undesirable results when

members of the press

report on the activities

of public officials.

Under the strict liability

rules of common law, a

public official would not

have to prove that a

reporter was aware that

a particular statement

about the official was

false in order to recover

from the reporter. This

could have the effect of

deterring members of

the press from

commenting on the

activities of a public

official.

Under the rules set forth

in Sullivan, a public

official cannot recover

from a person who

publishes a

communication about a

public official’s conduct

or fitness unless the

defendant knew that the

statement was false or

acted in reckless

disregard of the

statements truth or

falsity. This standard is

referred to as “actual

malice,” although malice

in this sense does not

mean ill-will. Instead,

the actual malice

standard refers to the

defendant’s knowledge

of the truth or falsity of

the statement. Public

officials generally

include employees of the

government who have

responsibility over

affairs of the

government. In order for

the First Amendment

rule to apply to the

public official, the

communication must

concern a matter related

directly to the office. Later cases expanded the

rule to apply to public

figures. A public figure

is someone who has

gained a significant

degree of fame or

notoriety in general or in

the context of a

particular issue or

controversy. Even

though these figures

have no official role in

government affairs, they

often hold considerable

influence over decisions

made by the government

or by the public.

Examples of public

figures are numerous

and could include, for

instance, celebrities,

prominent athletes, or

advocates who involve

themselves in a public

debate. Where speech is directed

at a person who is

neither a public official

nor a public figure, the

case of Gertz v. Robert

Welsh, Inc. (1974) and

subsequent decisions

have set forth different

standards. The Court in

Gertz determined that

the actual malice

standard established in

New York Times v.

Sullivan should not

apply where speech

concerns a private

person. However, the

Court also determined

that the common law

strict liability rules

impermissibly burden

publishers and

broadcasters.

Under the Restatement

(Second) of Torts, a

defendant who publishes

a false and defamatory

communication about a

private individual is

liable to the individual

only if the defendant

acts with actual malice

(applying the standard

under New York Times

v. Sullivan) or acts

negligently in failing to

ascertain whether a

statement was false or

defamatory .

D EFENSES TO D EFAMATION

Consent: Where a

plaintiff consents to the

publication of

defamatory matter about

him or her, then this

consent is a complete

defense to a defamation

action.

Truth:

Proving that the alleged

defamatory statement is

true will defend against

claims for damages. The

common law

traditionally presumed

that a statement was

false once a plaintiff

proved that the

statement was

defamatory. Under

modern law, a plaintiff

who is a public official

or public figure must

prove falsity as a

prerequisite for

recovery. Some states

have likewise now

provided that falsity is

an element of

defamation that any

plaintiff must prove in

order to recover. Where

this is not a requirement,

truth serves as an

affirmative defense to an

action for libel or

slander.

A statement does not

need to be literally true

in order for this defense

to be effective. Courts

require that the

statement is

substantially true in

order for the defense to

apply. This means that

even if the defendant

states some facts that are false, if the “gist” or

“sting” of the

communication is

substantially true, then

the defendant can rely

on the defense.

Absolute Privilege:

Some statements, while

libelous or slanderous,

are absolutely privileged

in the sense that the

statements can be made

without fear of a lawsuit

for slander. The best

example is a statement

made in a court of law.

An untrue statement

made by a witness about

a person in court which

damages that person’s

reputation will generally

not cause liability to the

witness as far as slander

is concerned. However,

if the statement is

untrue, and the person

knows the statement is

untrue, the crime of

perjury may have been

committed.

Some defendants are

protected from liability

in a defamation action

based on the defendant’s

position or status. These

privileges are referred to

as absolute privileges

and may also be

considered immunities.

In other words, the

defense is not

conditioned on the

nature of the statement

or upon the intent of the actor in making a false

statement. In

recognizing these

privileges, the law

recognizes that certain

officials should be

shielded from liability in

some instances.

Absolute privileges

apply to the following

proceedings and

circumstances: (1)

judicial proceedings; (2)

legislative proceedings;

(3) some executive

statements and

publications; (4)

publications between

spouses; and (5)

publications required by

law.

Absolute Privilege:

Some defendants are

protected from liability

in a defamation action

based on the defendant’s

position or status. These

privileges are referred to

as absolute privileges

and may also be

considered immunities.

In other words, the

defense is not

conditioned on the

nature of the statement

or upon the intent of the

actor in making a false

statement. In

recognizing these

privileges, the law

recognizes that certain

officials should be

shielded from liability in

some instances.

Absolute privileges

apply to the following

proceedings and

circumstances: (1)

judicial proceedings; (2)

legislative proceedings;

(3) some executive

statements and

publications; (4)

publications between

spouses; and (5)

publications required by

law.

Conditional Privilege:

Other privileges do not

arise as a result of the

person making the

communication, but

rather arise from the

particular occasion

during which the

statement was made.

These privileges are

known as conditional, or

qualified, privileges. A

defendant is not entitled

to a conditional privilege

without proving that the

defendant meets the

conditions established

for the privilege.

Generally, in order for a

privilege to apply, the

defendant must believe

that a statement is true

and, depending on the

jurisdiction, either have

reasonable grounds for

believing that the

statement was true or

not have acted recklessly

in ascertaining the truth

or falsity of the

statement. Conditional privileges

apply to the following

types of

communications:

■A statement that is

made for the protection

of the publisher’s

interest

■A statement that is

made for the protection

of the interests of a third

person

■A statement that is

made for the protection

of common interest

■A statement that is

made to ensure the well-

being of a family

member

■A statement that is

made where the person

making the

communication believes

that the public interest

requires communication

of the statement to a

public officer or other

official

■A statement that is

made by an inferior state

officer who is not

entitled to an absolute

privilege

Opinion:

Opinions are not

defamatory without

containing a factual

assertion. Defamation

requires that the

statement contains

specific facts that can be

proved untrue. For

example, “The waiters and waitresses at Acme

Restaurant are too slow

and the food is too

spicy.” This is a

statement of opinion. “I

got food poisoning at

Acme Restaurant” is

potentially a defamatory

statement if, in fact, the

restaurant can prove that

you never contracted

food poison.

D EFAMATION P ER S E

Damages for libel may

be limited to actual

damages unless there is

malicious intent. It does

not have to be proven

that actual harm to your

reputation occurred to

collect damages for libel

if it is defamatory per se,

such as:

* The communication

affects your business,

trade or profession (loss

of business, discharge,

demotion, etc.),

* Implies you committed

a crime,

* Leads on that you have

a loathsome disease,

* Or suggests that you

are somehow sexually

impure.

Useful suggestions for finalizing your ‘Libel Slander’ online

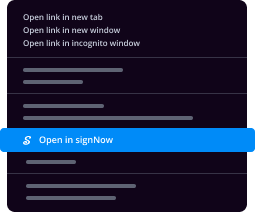

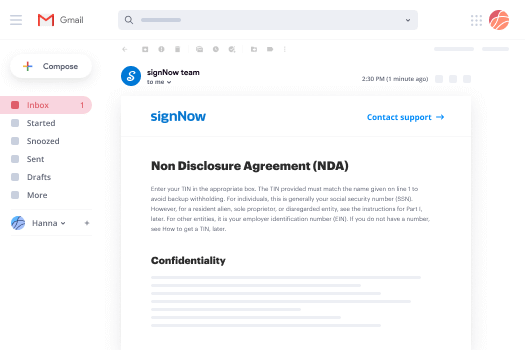

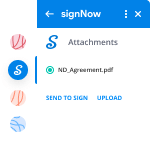

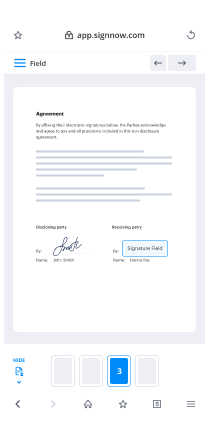

Exhausted by the inconvenience of dealing with paperwork? Look no further than airSlate SignNow, the premier electronic signature platform for individuals and small to medium-sized businesses. Bid farewell to the tedious process of printing and scanning documents. With airSlate SignNow, you can effortlessly fill out and sign documents online. Take advantage of the powerful features integrated into this user-friendly and cost-effective platform and transform your document management strategy. Whether you need to sign documents or collect eSignatures, airSlate SignNow makes it all simple, with just a few clicks.

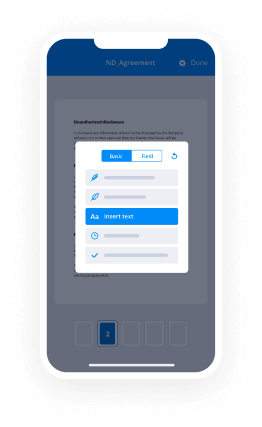

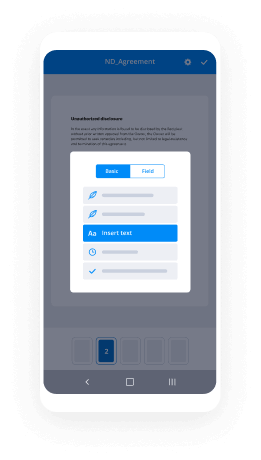

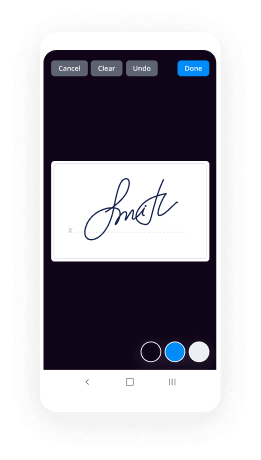

Follow this comprehensive guide:

- Log into your account or register for a free trial with our service.

- Click +Create to upload a file from your device, cloud storage, or our template collection.

- Open your ‘Libel Slander’ in the editor.

- Click Me (Fill Out Now) to finish the form on your end.

- Add and designate fillable fields for other participants (if needed).

- Proceed with the Send Invite settings to request eSignatures from others.

- Save, print your copy, or convert it into a reusable template.

No need to worry if you need to collaborate with others on your Libel Slander or send it for notarization—our solution provides you with everything needed to accomplish such tasks. Create an account with airSlate SignNow today and take your document management to the next level!