Journal of Business Research 58 (2005) 1437 – 1445

Emotions in consumer behavior: a hierarchical approach

Fleur J.M. Laros*, Jan-Benedict E.M. Steenkamp

Marketing Department, Tilburg University, P.O. Box 90153, 5000 LE Tilburg, The Netherlands

Received 1 December 2002; received in revised form 1 September 2003; accepted 1 September 2003

Abstract

A growing body of consumer research studies emotions evoked by marketing stimuli, products and brands. Yet, there has been a wide

divergence in the content and structure of emotions used in these studies. In this paper, we will show that the seemingly diverging research

streams can be integrated in a hierarchical consumer emotions model. The superordinate level consists of the frequently encountered general

dimensions positive and negative affect. The subordinate level consists of specific emotions, based on Richins’ (Richins, Marsha L.

Measuring Emotions in the Consumption Experience. J. Consum. Res. 24 (2) (1997) 127–146) Consumption Emotion Set (CES), and as an

intermediate level, we propose four negative and four positive basic emotions. We successfully conducted a preliminary test of this secondorder model, and compare the superordinate and basic level emotion means for different types of food. The results suggest that basic

emotions provide more information about the feelings of the consumer over and above positive and negative affect.

D 2004 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Consumer emotions; Hierarchy of emotions; Positive and negative affect; Basic emotions; Specific emotions

1. Introduction

After a long period in which consumers were assumed to

make largely rational decisions based on utilitarian product

attributes and benefits, in the last two decades, marketing

scholars have started to study emotions evoked by marketing stimuli, products and brands (Holbrook and Hirschman,

1982). Many studies involving consumer emotions have

focused on consumers’ emotional responses to advertising

(e.g., Derbaix, 1995), and the mediating role of emotions on

the satisfaction of consumers (e.g., Phillips and Baumgartner, 2002). Emotions have been shown to play an important

role in other contexts, such as complaining (Stephens and

Gwinner, 1998), service failures (Zeelenberg and Pieters,

1999) and product attitudes (Dube et al., 2003). Emotions

are often conceptualized as general dimensions, like

positive and negative affect, but there has also been an

interest in more specific emotions. Within the latter stream

of research, some researchers use a comprehensive set of

* Corresponding author. Tel.: +31 13 4668212; fax: +31 13 4662875.

E-mail address: F.Laros@uvt.nl (F.J.M. Laros).

0148-2963/$ - see front matter D 2004 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2003.09.013

specific emotions (Richins, 1997; Ruth et al., 2002). Other

researchers concentrate on one or several specific emotions,

such as surprise (e.g., Derbaix and Vanhamme, 2003), regret

(e.g., Inman and Zeelenberg, 2002; Tsiros and Mittal, 2000),

sympathy and empathy (Edson Escalas and Stern, 2003),

embarrassment (Verbeke and Bagozzi, 2003) and anger

(Bougie et al., 2003; Taylor, 1994).

Despite this emerging body of research, progress on the

use of emotions in consumer behavior has been hampered

by ambiguity about two interrelated issues, viz., the

structure and content of emotions (Bagozzi et al., 1999).

First, with regard to structure, some researchers examine all

emotions at the same level of generality (e.g., Izard, 1977),

whereas others specify a hierarchical structure in which

specific emotions are particular instances of more general

underlying basic emotions (Shaver et al., 1987; Storm and

Storm, 1987). Second, and relatedly, there is debate

concerning the content of emotions. Should emotions be

most fruitfully conceived as very broad general factors, such

as pleasure/arousal (Russell, 1980) or positive/negative

affect (Watson and Tellegen, 1985)? Alternatively, appraisal

theorists (see, e.g., Frijda et al., 1989; Roseman et al., 1996;

Smith and Lazarus, 1993) argue that specific emotions

�1438

F.J.M. Laros, J.-B.E.M. Steenkamp / Journal of Business Research 58 (2005) 1437–1445

should not be combined in broad emotional factors, because

each emotion has a distinct set of appraisals. The confusion

concerning structure and content of emotions has hindered

the full interpretation and use of emotions in consumer

behavior theory and empirical research (Bagozzi et al.,

1999).

The purpose of our paper is twofold. First, we integrate

seemingly opposing research streams in psychology and

consumer behavior by developing a hierarchical model of

consumer emotions. We will show that the general

dimensions with positive and negative affect are the

superordinate and most abstract level at which emotions

can be defined. The subordinate level consists of specific

consumer emotions. We will develop an intermediate level

with basic emotions that links these two levels. Second, we

conduct a preliminary test of this proposed structure and

compare the means for positive and negative affect with

those of the basic emotions for four different food types.

2. Emotions in consumer research

This section will briefly discuss an illustrative set of

consumer studies on emotions (see Table 1 for an overview).

Several studies focused on the emotional responses to

ads. Holbrook and Batra (1987) developed their own

emotional scale based on an in-depth review of the

literature. They uncovered a pleasure, arousal and domination dimension in their data, and showed that these

emotions mediate consumer responses to advertising. Edell

and Burke (1987) also created their own emotion list and

found that feelings play an important role in the prediction

of the ad’s effectiveness. They proposed three factors: an

upbeat, negative, and warmth factor. Olney et al. (1991)

showed that the emotional dimensions pleasure and arousal

mediate the relation between ad content and attitudinal

components, and consequently viewing time of an ad.

They used part of Mehrabian and Russell’s (1974) scale.

Derbaix (1995) replicated the research of Edell and Burke

(1987) in a natural setting. His emotion words were based

on a prestudy, and uncovered a positive and negative

factor. Steenkamp et al. (1996) investigated the relations

between arousal potential, arousal, and ad evaluation, with

need for stimulation as a moderator. They based their

arousal dimension on the scale of Mehrabian and Russell

(1974).

In the satisfaction literature, Westbrook (1987) was one

of the first to investigate consumer emotional responses to

product/consumption experiences and their relationship to

several central aspects of postpurchase processes. Oliver

(1993) extended this work by showing that emotional

responses mediate the effects of product attributes on

satisfaction. Both studies relied on Izard’s (1977) taxonomy

of fundamental affects, and found positive and negative

affect as underlying emotion dimensions. Mano and Oliver

(1993) investigated the structural interrelationship among

evaluations, feelings, and satisfaction in the postconsumption experience. They combined Watson et al.’s (1988)

PANAS scale and Mano’s (1991) circumplex scale. Both

three dimensions—similar to the upbeat, negative, and

warmth factors of Edell and Burke (1987)—and two

dimensions—positive and negative affect—were uncovered,

but only the latter dimensions were used in the studies.

Dube and Morgan (1998) modeled trends in consumption

emotions and satisfaction in order to predict retrospective

global judgments of services. They used the PANAS scale

(Watson et al., 1988) and uncovered positive and negative

affect. Phillips and Baumgartner (2002) confirmed the

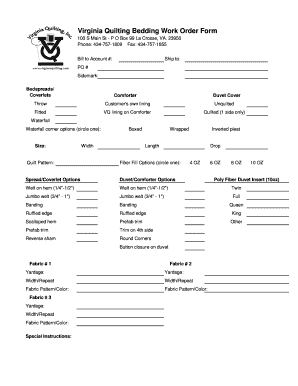

Table 1

Overview of consumer research using emotions as a main variable

Reference

Emotion measure used

Resulting structure

Edell and Burke (1987)

Holbrook and Batra (1987)

Westbrook (1987)

Olney et al. (1991)

Holbrook and Gardner (1993)

Mano and Oliver (1993)

Edell and Burke (1987)

Holbrook and Batra (1987)

Izard (1977)

Mehrabian and Russell (1974)

Russell et al. (1989)

Watson et al. (1988); Mano (1991)

Oliver (1993)

Derbaix (1995)

Steenkamp et al. (1996)

Nyer (1997)

Richins (1997)

Izard (1977)

Derbaix (1995)

Mehrabian and Russell (1974)

Shaver et al. (1987)

Richins (1997)

Dube and Morgan (1998)

Phillips and Baumgartner (2002)

Ruth et al. (2002)

Watson et al. (1988)

Edell and Burke (1987)

Shaver et al. (1987)

Smith and Bolton (2002)

Smith and Bolton (2002)

Upbeat, negative, and warm

Pleasure, arousal, and domination

Positive and negative affect

Pleasure and arousal

Pleasure and arousal

Upbeat, negative and warm

Positive and negative

Positive and negative affect

Positive and negative affect

Arousal

Anger, joy/satisfaction, and sadness

Anger, discontent, worry, sadness, fear, shame,

envy, loneliness, romantic love, love, peacefulness,

contentment, optimism, joy, excitement, and surprise

Positive and negative affect

Positive and negative affect

Love, happiness, pride, gratitude, fear, anger, sadness,

guilt, uneasiness, and embarrassment

Anger, discontent, disappointment, self-pity, and anxiety

�F.J.M. Laros, J.-B.E.M. Steenkamp / Journal of Business Research 58 (2005) 1437–1445

importance of including positive and negative affect in

explaining satisfaction. Smith and Bolton (2002) investigated the role of consumer emotions in the context of

service failure and recovery encounters. They used content

analysis for the responses of the participants and grouped

the (negative) emotion words of consumers in five

categories.

Holbrook and Gardner (1993) investigated the relation

between the emotional dimensions pleasure and arousal and

the duration of a consumption experience, which was in

their case, listening to music. They used Russell et al.’s

(1989) Affect Grid to measure pleasure and arousal of the

musical stimuli.

Nyer (1997) and Ruth et al. (2002) focused on defining

the antecedents rather than the consequences of emotions.

1439

Nyer (1997) showed that the appraisals of goal relevance,

goal congruence, and coping potential are determinants of

several basic consumption emotions. These emotions were

mainly based on Shaver et al. (1987). Ruth et al. (2002)

explored the cognitive appraisals of situations and their

correspondence to 10 experienced emotions. They also used

emotions based on the hierarchical structure of Shaver et al.

(1987).

In summary, this overview shows that there is wide

divergence in the content of emotions studied in consumer

research. Studies often use different scales to measure

emotions and focus on different emotions. In spite of this,

consumer researchers frequently use, or exploratory data

analysis yields, a small number of dimensions (Bagozzi et al.,

1999). Among these, the classification of emotions in

Table 2

Emotion words

Negative emotion words

Positive emotion words

Aggravationa,b,c, Agitationa,b,c, Agonyb,c, Alarmb,c,d, Alienationb,

Anger a,b,c,d,e,f,g, Anguisha,b,c, Annoyancea,b,c,d,e,f,h, Anxietya,b,c,e,

Apologeticc, Apprehensiona,b,c, Aversione, Awfulc, Badc, Bashfulc,

Betrayalc, Bitternessa,b,c, Bluea,c,i, Botheredc, Cheerlessa, Confusedh,

Consternationc, Contemptb,c,e,g, Crankyc, Crossc, Crushedh, Cryc,

Defeatb, Deflateda,b, Defensivec, Dejectiona,b,c, Demoralizedc,

Depression a,b,c,d,h, Despairb,c, Devastationc, Differentc,

Disappointmenta,b,c,e,f, Discomfortc, Discontent a,c, Discouragedc,

Disenchantmentc, Disgusta,b,c,e,g,h, Dislikeb,c,g, Dismayb,c,

Displeasurea,b,c, Dissatisfieda,c, Distressa,b,c,d,g,i,j, Distrustc,e, Disturbedc,

Downa,c, Dreadb,c, Dumbc, Edgyc, Embarrassment a,b,c, Emptya,c,

Envy a,b,c, Exasperationb, Fear b,c,d,e,f,g,h,i,j, Fed-upa, Ferocityb, Flustereda,

Forlornc, Foolishc, Franticc, Frighta,b,c,h, Frustration a,b,c,d,f,g, Furya,b,c,

Gloomb,c,d,h, Glumnessb, Griefa,b,c,f, Grouchinessb,c,i, Grumpinessb,c,i,

Guilt b,c,e,g,j, Heart-brokena,c, Hateb,c,Hollowc, Homesickness a,b,c,

Hopelessnessb,c, Horriblec, Horrora,b,c,f, Hostility b,c,h,i,j, Humiliation b,c,

Hurta,b,c, Hysteriab, Impatienta,c, Indignantc, Inferiorc, Insecurityb,

Insultb,c, Intimidatedh, Iratea,c, Irkeda, Irritation a,b,c,h,j, Isolationb,c,

Jealousy a,b,c,e, Jitteryi,j, Joylessa, Jumpyc, Loathingb, Loneliness a,b,c,i,

Longingc, Lossc, Lovesicka, Lowa,c, Mada,c, Melancholyb,c, Misery a,b,c,d,

Misunderstoodc, Mopingc, Mortificationa,b, Mournfulc, Neglectb,c,

Nervousness a,b,c,i,j, Nostalgiac, Offendedh, Oppressedc, Outragea,b,c,

Overwhelmeda, Painc, Panic b,c, Petrifieda,c, Pitya,b,c, Puzzledh, Rageb,c,e,

Regreta,b,c,e,g, Rejectionb,c, Remorsea,b,c, Reproachfulc, Resentmenta,b,c,

Revulsionb, Ridiculousc, Rottenc, Sadness a,b,c,d,e,f,g,h,i, Scared a,c,h,j,

Scornb,c,i, Self-consciousc, Shame ,a,b,c,e,g,j, Sheepishc, Shocka,b,c, Shyc,

Sickeneda,c, Smallc, Sorrowa,b,c,e,i, Spiteb, Startlede,h, Strainedc, Stupidc,

Subduedc, Sufferingb,c, Suspensec, Sympathyb, Tenseness b,c,h, Terriblec,

Terrora,b,c, Threatenedh, Tormenta,b,c, Troubledc, Tremulousc, Uglyc,

Uneasinessa,b,c, Unfulfilled, Unhappinessa,b,c,i, Unpleasanth, Unsatisfiedc,

Unwantedc, Upseta,c,e,j, Vengefulnessb,c, Wantc, Wistfulc, Woeb,c,

Worry b,c, Wrathb,c, Yearningc

Acceptancec,h, Accomplishedc, Activei,j, Admirationc, Adorationb,c,

Affectionb,c, Agreementc, Alerth,j, Amazementb, Amusementa,b,c,

Anticipationb,c, Appreciationc, Ardentc, Arousala,b,d, Astonishmentb,d,i,

At easea,d, Attentiveh,j, Attractionb,c, Avidc, Blissb, Bravec,

Calm a,d, Caringb,c, Charmeda, Cheerfulnessa,b,c,h, Comfortablec,

Compassionb,c, Consideratec, Concernc, Contentment a,b,c,d,I,

Courageousc, Curioush, Delighta,b,c,d,h, Desireb,c, Determinedj,

Devotionc, Eagernessb,c, Ecstasya,b,c, Elationa,b,c,i, Empathyc, Enchantedc,

Encouraging c, Energeticf, Enjoymentb,c,f, Entertainedc, Enthrallmentb,

Enthusiasm b,c,e,f,i,j, Euphoriab,c, Excellentc, Excitement a,b,c,d,f,i,j,

Exhilarationb,f Expectantc, Exuberantc, Fantasticc, Fascinatede, Finec,

Fondnessb,c, Forgivingc, Friendlyc, Fulfillment c, Gaietyb,c, Generousc,

Gigglyc, Givingc, Gladnessa,b,c,d, Gleeb,c, Goodc, Gratitudec, Greatc,

Happiness a,b,c,d,e,f,h,i, Harmonyc, Helpfulc,h, Highc, Hope b,c,g, Hornyc,

Impressedc, Incrediblec, Infatuationb,c, Inspiredj, Interestedf,j, Jollinessb,

Jovialityb, Joy a,b,c,e,f,g, Jubilationb,c, Kindlyc,i, Lightheartedc, Likingb,c,g,

Longingb, Love a,b,c,e, Lustb,c, Merrimentc, Moveda, Nicec, Optimism b,

Overjoyeda,c, Passion a,b,c, Peaceful c,f, Peppyi, Perfectc, Pityc, Playfulc,

Pleasure a,c,d,f,i, Pridea,b,c,e,f,g,j, Protectivec, Raptureb, Reassuredc, Regardc,

Rejoicec, Relaxedc,d,f, Releasec, Relief a,b,c,e,f,g, Respectc, Reverencec,

Romantic c, Satisfactiona,b,c,d,f,i, Securec, Sensationalc, Sensitivec, Sensualc,

Sentimentality b,c, Serened,c, Sexy c, Sincerec, Strongi,j, Superc, Surpriseb,e,f,i,

Tendernessb,c, Terrificc, Thoughtfulc, Thrill a,b,c, Toucheda, Tranquilityc,

Triumphb, Trustc,h, Victoriousc, Warm-hearted c,i, Wonderfulc, Worshipc,

Zealb, Zestb

Note: The emotion words of Richins’ CES (1997) are in italics.

a

Morgan and Heise (1988).

b

Shaver et al. (1987).

c

Storm and Storm (1987).

d

Russell (1980).

e

Frijda et al. (1989).

f

Havlena et al. (1989).

g

Roseman et al. (1996).

h

Plutchik (1980).

i

Watson and Tellegen (1985).

j

Watson et al. (1988).

�1440

F.J.M. Laros, J.-B.E.M. Steenkamp / Journal of Business Research 58 (2005) 1437–1445

positive and negative affect appears to be the most popular

conceptualization (see Table 1).

3. Positive and negative affect

Many papers acknowledge that positive and negative

affect are bever present in the experience of emotionsQ

(Diener, 1999, p. 804; see also Berkowitz, 2000; Watson

et al., 1999). We have content-analyzed 10 seminal studies

in psychology on emotions and emotion words (Frijda et al.,

1989; Havlena et al., 1989; Morgan and Heise, 1988;

Plutchik, 1980; Roseman et al., 1996; Russell, 1980; Shaver

et al., 1987; Storm and Storm, 1987; Watson and Tellegen,

1985; Watson et al., 1988). We were able to classify all

emotion words as either a positive or negative emotion (see

Table 2). Table 2 shows the emotion words and indicates

which studies included a particular word as a positive or

negative emotion word in their structure. The number of

references for each emotion word illustrates to what degree

researchers agree that this is an emotion word. For example,

the emotion words fear, sadness, and happiness appear

almost in every emotion structure, whereas others, like

mournful, forlorn, and zeal, are only mentioned occasionally.

In addition, Table 2 supports the notion that there are more

negative than positive emotion words (Morgan and Heise,

1988).

Yet, which of these many emotion words should be used to

measure consumer emotions? To address this issue, we can

use the important study by Richins (1997). Based on

extensive research, she constructed the Consumption Emotion Set (CES). This scale includes most, if not all, emotions

that can emerge in consumption situations and was developed

to distinguish the varieties of emotion associated with

different product classes. Table 2 reveals that the words

included in the CES (in italics) are among the most frequently

encountered words in the psychological emotion literature,

and can be easily divided in positive and negative affect.

Advantages of the division in positive and negative affect

are that (1) the model can be kept simple and (2) the

combination of a person’s positive and negative affect is

indicative of his/her attitude. The disadvantage is that

important distinctions among different positive and negative

emotions disappear (Lerner and Keltner, 2000; 2001). Thus,

more precise information about the feelings of the consumer

is lost (Bagozzi et al., 1999). Because different emotions can

have different behavioral consequences, it is important to

know, for example, whether a failure in a product or service

elicits feelings of anger or sadness. Both angry and sad

people feel that something wrong has been done to them,

but whereas sad people become inactive and withdrawn, the

angry person becomes more energized to fight against the

cause of anger (Shaver et al., 1987). Several studies have

shown how important it is to take into account differences

across emotions of the same valence (Lerner and Keltner,

2000; 2001; Zeelenberg and Pieters, 1999).

4. A hierarchy of consumer emotions

The research streams supporting the different emotion

structures (positive/negative vs. specific emotions) seem

opposing, but can in fact be seen as complementing. Shaver

et al. (1987) and Storm and Storm (1987) have suggested

that emotions can be grouped into clusters, yielding a

hierarchical structure. The most general, superordinate, level

consists of positive and negative affect. The next level is

considered as the basic emotion level, and the lowest,

subordinate, level consists of groups of individual emotions

that form a category named after the most typical emotion of

that category. Along the lines of the hierarchical structures

of Shaver et al. (1987) and Storm and Storm (1987), we thus

propose that consumer emotions can be considered at

different levels of abstractness.

Our hierarchy of consumer emotions distinguishes

between positive and negative affect at the superordinate

level. The specific consumer emotions based on Richins’

(1997) CES encompass the subordinate level. Which basic

emotions should constitute the intermediate level, however,

is less clear. Basic emotions are believed to be innate and

universal, but because there are different ways to conceive

emotions (facial, e.g., Ekman, 1992; biosocial, e.g., Izard,

1992; brain, e.g., Panksepp, 1992), there is also disagreement about which emotions are basic (Turner and Ortony,

1992). Ortony and Turner (1990) have shown that 14

different emotion theorists proposed 14 different sets of

basic emotions. Table 3 shows the usage frequency of the

basic emotions in the different structures reviewed by

Ortony and Turner (1990). With few exceptions, the basic

Table 3

Basic emotions in the psychological literature (adapted from Ortony and

Turner, 1990)

Acceptancea, Angera,b,c,d,e,f,g,h,i, Anticipationa, Anxietyf,h,j, Aversionb,

Contemptd,i, Contentmenth, Courageb, Dejectionb, Desireb,k, Despairb,

Disgusta,c,d,e,f,h,i, Distressd,i, Elatione, Expectancyl, Feara,b,c,d,e,g,h,i,l,m,n,

Grief m, Guiltd, Happinessf,h,k,o, Hateb, Hopeb, Hostilityh, Interestd,k,

Joya,c,d,g,i,j, Likingh, Loveb,g,h,m,n, Painh,p, Panicl, Pleasurep, Prideh,

Ragej,l,m,n, Sadnessa,b,c,f,g,h,o, Shamed,h,i, Sorrowk, Subjectione,

Surprisea,c,d,i,k, Tendere, Wondere,k

a

Plutchik (1980).

Arnold (1960).

c

Ekman et al. (1982).

d

Izard (1971).

e

McDougal (1926).

f

Oatley and Johnson-Laird (1987)

g

Shaver et al. (1987).

h

Storm and Storm (1987).

i

Tomkins (1984).

j

Gray (1982).

k

Frijda (1986).

l

Panksepp (1982).

m

James (1884).

n

Watson (1930).

o

Weiner and Graham (1984).

p

Mowrer (1960).

b

�F.J.M. Laros, J.-B.E.M. Steenkamp / Journal of Business Research 58 (2005) 1437–1445

emotions from Table 3 are among the most frequently

mentioned emotion words in Table 2.

To develop a set of basic consumer emotions, we draw

on the hierarchical structures of Shaver et al. (1987) and

Storm and Storm (1987), and Table 3. Some basic emotion

words are mentioned in most of the structures (see Table 3).

These are anger, fear, love, sadness, disgust, joy, and

surprise. Anger, fear, love and sadness are basic emotions in

both the structures of Shaver et al. (1987) and Storm and

Storm (1987), and will be retained in our structure. Disgust

is not included in the structure of Richins (1997) and

therefore excluded as a basic consumption emotion.

Surprise was excluded for several reasons. First, it is a

neutral emotion (Storm and Storm, 1987) and therefore

impossible to classify as a positive or negative emotion.

Second, when participants were required to list emotions,

surprise was hardly mentioned (Fehr and Russell, 1984).

Following Storm and Storm (1987), we added the

emotion shame to the basic negative emotions. Anger,

sadness, and fear are all emotions elicited by situations

caused by others or circumstances, whereas shame is caused

by a negative action of consumers themselves (Roseman et

al., 1996).

The positive emotions can be roughly divided in interpersonal emotions and emotions without interpersonal

reference (Storm and Storm, 1987). The interpersonal

emotions are covered by love and its specific emotion

words, but there are distinct differences between the

emotions that are not interpersonal. Following Storm and

Storm (1987), we therefore replaced the more general term

joy by the basic emotions contentment, happiness, and

pride. Contentment is low in arousal and passive, whereas

happiness is higher in activity and a reactive positive

emotion. Pride, on the other hand, concerns feelings of

superiority. Due to these differences, we argue that it is

better to include these basic emotions separately rather than

all under one large basic emotion of joy.

Our proposed hierarchy thus consists of three levels: the

superordinate level with positive and negative affect, the

basic level with four positive and four negative emotions,

and the subordinate level with specific emotions. The final

1441

result can be seen in Fig. 1. Next, we will conduct a

preliminary test of our hypothesized structure.

5. Method

5.1. Sample and procedure

Data were collected in a nationally representative sample

among 645 Dutch consumers using a questionnaire. The

market research agency GfK carried out the data collection.

Of the respondents, 53.6% were women, 58.3% were

responsible for the daily grocery shopping, and 69.1% were

the main wage earner of the household. The average

household size was 2.39 persons and all levels of education

and income were represented. The average age was 48

years and ranged between 16 and 91 with a fairly normal

spread.

Respondents were asked to indicate to what extent they

experience 33 specific emotions for one (randomly

assigned) type of food (genetically modified food, functional food, organic food, or regular food). Thus, we

measure emotions at a general, product-type level of

categorization. In The Netherlands, these types of foods

are widely known, the exception being functional foods

(this was confirmed in discussions with industry experts).

Therefore, respondents who rated their emotions for functional foods received additional explanation: bFunctional

foods are food products that have been enriched or

modified. The reason for this is to make the product

healthier or to prevent diseases (e.g., milk with extra

calcium, margarine with additives to lower the cholesterol

level)Q.

5.2. Measures

With some exceptions, the emotion words shown in Fig.

1 were used. Emotions were rated on a five-point Likert

scale ranging from I feel this emotion not at all (1) to I feel

this emotion very strongly (5). In our empirical test, we

omitted the basic emotions bloveQ and bprideQ, and the

Fig. 1. Hierarchy of consumer emotions.

�1442

F.J.M. Laros, J.-B.E.M. Steenkamp / Journal of Business Research 58 (2005) 1437–1445

emotion words benviousQ and bjealousQ. bLoveQ is demonstrated to be mainly experienced in the case of sentimental

products, like mementos and gifts (Richins, 1997). The

latter three emotions are interpersonal and less applicable in

the case of widely available food. The emotion bprideQ

generally occurs when a consumer feels superior compared

to another person, whereas the emotions benvyQ and

bjealousyQ occur when consumers feel that another person

has something more or better than them. Thus, the basic

emotions in our analyses are as follows: anger, fear, sadness,

shame, contentment, and happiness, measured in total by 33

specific emotion words.

5.2. Stability of the emotions structure across food types

Before we can test our second-order hierarchical model

of consumer emotions, we have to establish whether we can

pool the data across the four food types. We do this in two

ways. First, we assess whether principal component analysis

yields the same factor structure in each of the four food

groups. The Bartlett’s test of sphericity is significant for all

four foods, and the measure of sampling adequacy ranges

between .86 (organic food) and .92 (genetically modified

food), which means that principal component analysis can

be applied. The scree test indicated two factors in all four

groups, explaining between 48% (regular food) and 60%

(genetically modified food) of the variance. The factor

structures (after rotation) were highly similar, Tucker’s

congruence coefficient always being greater than .95

( P b.01; Cattell, 1978).

A second way to assess the similarity of the four food

groups is to test for the invariance of the covariance matrices

across the four groups using LISREL 8.50 (Steenkamp and

Baumgartner, 1998). The fit was good, given the large

sample and high number of degrees of freedom (Baumgartner and Homburg, 1996): v 2(1683)=3845.90 ( Pb.001);

CFI=.86; TLI=.82. Hence, we can pool the data across the

different food types.

6. Results

6.1. Testing the proposed model

We used LISREL 8.50 to test the proposed hierarchical

emotions model. The standardized parameter estimates of

the second-order factor analysis are reported in Fig. 2.

Model fit is acceptable: v 2(490)=3036.79 ( Pb.001),

CFI=.84, TLI=.83. Although the v 2 was highly significant

(not unexpected given the large sample size; Anderson and

Gerbing, 1988), other indicators suggest reasonable model

fit, especially considering that fit is adversely affected by

model complexity (Baumgartner and Homburg, 1996;

Bollen, 1989; Bone et al., 1989). In addition, the fit

measures are in line with simulation results (see Gerbing

and Anderson, 1993 for a review) and compare favorably to

other models with similar degrees of freedom (e.g.,

Netemeyer et al., 1991; Richins and Dawson, 1992; Wong

et al., 2003).

All factor loadings were significant at P b.001, the

average loading being .73. Only the factor loading of the

emotion nostalgia on the basic emotion sadness was below

.40. A possible explanation for this is that nostalgia involves

complex emotional responses and can have both a positive

and a negative connotation (Holak and Havlena, 1998). The

correlation between the second-order factors positive and

negative affect was significant (r= .35, Pb.01), confirming

earlier results found in consumer research (e.g., Westbrook,

1987; Phillips and Baumgartner, 2002).

These results support the convergent and discriminant

validity of our model (Steenkamp and Van Trijp, 1991). The

reliability of our measures was high. Cronbach alphas were

a=.94 and a=.95 for the dimensions positive and negative

affect, respectively. The basic emotions yielded the following reliabilities: anger (a=.88), fear (a=.88), sadness

(a=.76), shame (a=.74), contentment (a=.86), and happiness (a=.92).

6.2. Comparison of the superordinate level with the basic

emotions

Although the emotion structure is similar for the four

food groups, that does not imply that the various foods

evoke the same emotional intensity. Table 4 provides the

mean scores for the superordinate dimensions positive and

negative affect and for the basic emotions.

ANOVA with multiple comparisons (LSD) was used to

investigate whether the mean values across food groups are

significantly different. Participants experience significantly

more negative affect and less positive affect for genetically

modified foods than for the other food groups. Yet, the

basic emotions show differences among the food types that

would have been lost if only positive and negative affect

had been considered. Both the basic emotions fear and

contentment contain additional subtle distinctions across the

food groups. The negative affect experienced by consumers

is similar for functional, organic, and regular food. Yet,

consumers feel a lot more fearful concerning functional

food than for organic and regular food. Concerning the

positive emotions, contentment has very low values for

organic food compared to functional and regular food.

These nuances, however, are wiped away for positive

affect.

To demonstrate the usefulness of basic emotions for

understanding the consumer’s feelings, we will take a closer

look at one of the food groups. Genetically modified food

represents a controversial topic in contemporary society,

and previous research (e.g., Bredahl, 2001) has shown that

consumers have a rather negative attitude towards this type

of food. The scores on negative and positive affect support

this, but the basic emotions indicate more clearly how

consumers feel. Participants do not feel sad or ashamed, but

�F.J.M. Laros, J.-B.E.M. Steenkamp / Journal of Business Research 58 (2005) 1437–1445

1443

Fig. 2. Results of second-order factor analysis.

are very angry and afraid. This means that they feel

energized and powerful rather than inactive, and feel that

they themselves are not to be blamed, but someone else is.

In addition, genetically modified food elicits strong

associations of risk and uncertainty leading to feelings of

fear.

Table 4

Differences in the intensity of the superordinate and basic emotions for the food groups

Emotion

GMF

Functional

Organic

Regular

F

P value

Negative affect

Anger

Sadness

Fear

Shame

Positive affect

Contentment

Happiness

1.99a

2.19a

1.79a

2.16a

1.65a

1.68a

1.82a

1.64a

1.45b

1.51b

1.46b

1.57b

1.32b

2.41b,c

2.69b

2.32b

1.43b

1.47b

1.47b

1.40c

1.29b

2.32c

2.40c

2.29b

1.46b

1.55b

1.47b

1.43c

1.31b

2.48b

2.81b

2.37b

31.25

34.49

11.99

46.06

11.30

40.09

47.38

33.64

b.001

b.001

b.001

b.001

b.001

b.001

b.001

b.001

Note: Different supercripts reflect a significant difference of the intensity at a p-value b0.05.

�1444

F.J.M. Laros, J.-B.E.M. Steenkamp / Journal of Business Research 58 (2005) 1437–1445

7. Conclusion

References

Based on our literature review, we concluded that despite

the different ways to measure emotions, positive and negative

affect are frequently employed as general emotion dimensions. Important nuances, however, are lost if emotions of the

same valence are collapsed together. This paper therefore

proposed a hierarchical model of consumer emotions (Fig. 1)

to integrate the different research streams concerning emotion

content and structure. This model specifies emotions at three

levels of generality. At the superordinate level, it distinguishes between positive and negative affect. This is

generally considered to be the most abstract level at which

emotions can be experienced (e.g., Berkowitz, 2000; Diener,

1999). At the level of basic emotions, we specify four positive

(contentment, happiness, love, and pride) and four negative

(sadness, fear, anger, and shame). At the subordinate level,

we distinguish between 42 specific emotions based on

Richins’ (1997) CES. Our empirical study provides support

for the proposed model and suggests that the basic emotions

allow for a better understanding of the consumers’ feelings

concerning certain food products compared to only positive

and negative affect. Note that not in all situations this model

need be used as a whole. Dependent on the research question,

only part of the model may be used. However, even in such

cases, the researcher can still relate his/her specific results to

the broader structure of our emotions. This makes it easier for

emotions research to cumulatively build on each other and to

identify gaps in our knowledge.

Our study has several limitations, which offer avenues

for future research. First, we excluded two basic emotions

(love and pride) from our empirical analysis. Future

research is needed to validate the whole hierarchy of

emotions, and to test our model on other products and

services. Second, future research can expand the set of

specific consumer emotions. Possible candidates include the

negative emotions regret and disappointment that recently

received a great deal of attention in consumer research (e.g.,

Inman and Zeelenberg, 2002; Tsiros and Mittal, 2000;

Zeelenberg and Pieters, 1999). Regret stems from bad

decisions, whereas disappointment originates from disconfirmed expectancies (Zeelenberg and Pieters, 1999). We

thus propose that regret can be positioned under the basic

emotion shame, and disappointment under the basic

emotion sadness (Zeelenberg et al., 1998), but future

research should investigate this.

Third, future research can investigate whether the set of

basic emotions has greater explanatory power than positive

and negative affect. Our exploratory analysis indicates this,

but future research should test this hypothesis. Fourth, we

tested our emotions model in The Netherlands. The further

advancement of consumer research as an academic

discipline requires that the validity of our theories and

measures and their degree of general validity and boundary

conditions be tested in different countries (Steenkamp and

Burgess, 2002).

Anderson James C, Gerbing David W. Structural equation modeling in

practice: a review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol Bull

1988;103(3):411 – 23.

Bagozzi Richard P, Gopinath Mahesh, Nyer Prashanth U. The role of

emotions in marketing. J Acad Mark Sci 1999;27(2):184 – 206.

Baumgartner Hans, Homburg Christian. Applications of structural equation

modeling in marketing and consumer research: a review. Int J Res Mark

1996;13(2):139 – 61.

Berkowitz Leonard. Causes and consequences of feelings. New York7

Cambridge University Press; 2000.

Bollen Kenneth A. Structural equations with latent variables. New York7

Wiley; 1989.

Bone Paula Fitzgerald, Sharma Subhash, Shimp Terence. A bootstrap

procedure for evaluating goodness-of-fit indices of structural equation

and confirmatory factor models. J Mark Res 2003;26(1):105 – 11.

Bougie Roger, Pieters Rik, Zeelenberg Marcel. Angry customers don’t

come back, they get back: the experience and behavioral implications of

anger and dissatisfaction in services. Journal of the Academy of

Marketing Science; 2003;31(4):377 – 393.

Bredahl Lone. Determinants of consumer attitudes and purchase intentions

with regard to genetically modified foods—results of a cross-national

survey. J Consum Policy 2001;24:23 – 61.

Cattell RB. The scientific use of factor analysis in behavioral and life

sciences. New York7 Plenum; 1978.

Derbaix Christian M. The impact of affective reactions on attitudes toward

the advertisement and the brand: a step toward ecological validity. J

Mark Res 1995;32(4):470 – 9.

Derbaix Christian M, Vanhamme Joelle. Inducing word-of-mouth by

eliciting surprise—a pilot investigation. J Econ Psychol 2003;24:

99 – 116.

Diener Ed. Introduction to the special section on the structure of emotion. J

Pers Soc Psychol 1999;76(5):803 – 4.

Dube Laurette, Morgan Michael S. Capturing the dynamics of in-process

consumption emotions and satisfaction in extended service transactions.

Int J Res Mark 1998;15:309 – 20.

Dube Laurette, Cervellon Marie-Cecile, Jingyuan Han. Should consumer

attitudes be reduced to their affective and cognitive bases? Validation of

a hierarchical model. Int J Res Mark 2003;20:259 – 72.

Edell Julie A, Burke Marian C. The power of feelings in understanding

advertising effects. J Consum Res 1987;14(4):421 – 33.

Edson Escalas Jennifer, Stern Barbara B. Sympathy and empathy: emotional

responses to advertising dramas. J Consum Res 2003;29(4):566 – 78.

Ekman Paul. Are there basic emotions? Psychol Rev 1992;99(3):550 – 3.

Fehr Beverly, Russell James A. Concept of emotion viewed from a

prototype perspective. J Exp Psychol Gen 1984;113:464 – 86.

Frijda Nico H, Kuipers Peter, Ter Schure Elisabeth. Relations among

emotion, appraisal, and emotional action readiness. J Pers Soc Psychol

1989;57(2):212 – 28.

Gerbing David W, Anderson James C. Monte Carlo evaluations of

goodness-of-fit indices for structural equation models. In: Bollen

Kenneth A, Long J. Scott, editors. Testing structural equation models.

Newbury Park, CA7 Sage; 1993. p. 40 – 65.

Havlena William J, Holbrook Morris B, Lehmann Donald R. Assessing the

validity of emotional typologies. Psychol Market 1989;6:97 – 112.

Holak Susan L, Havlena William J. Feelings, fantasies, and memories: an

examination of the emotional components of nostalgia. J Bus Res

1998;42(3):217 – 27.

Holbrook Morris B, Batra Rajeev. Assessing the role of emotions as

mediators of consumer responses to advertising. J Consum Res 1987;

14(3):404 – 20.

Holbrook Morris B, Gardner Meryl P. An approach to investigating the

emotional determinants of consumption durations: why do people

consume what they consume for as long as they consume it? J Consum

Psychol 1993;2(2):123 – 42.

�F.J.M. Laros, J.-B.E.M. Steenkamp / Journal of Business Research 58 (2005) 1437–1445

Holbrook Morris B, Hirschman Elizabeth C. The experiential aspects of

consumption: consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. J Consum Res

1982;9(2):132 – 40.

Inman Jeffrey J, Zeelenberg Marcel. Regret in repeat purchase versus

switching decisions: the attenuating role of decision justifiability. J

Consum Res 2002;29(1):116 – 28.

Izard Carroll. Human emotions. New York7 Plenum; 1977.

Izard Carroll. Basic emotions, relations among emotions, and emotion–

cognition relations. Psychol Rev 1992;99(3):561 – 5.

Lerner Jennifer S, Keltner Dacher. Beyond valence: toward a model of

emotion-specific influences on judgment and choice. Cogn Emot

2000;14(4):473 – 93.

Lerner Jennifer S, Keltner Dacher. Fear, anger and risk. J Pers Soc Psychol

2001;81(1):146 – 59.

Mano Haim. The structure and intensity of emotional experiences: method

and context convergence. Multivariate Behav Res 1991;26(3):389 – 411.

Mano Haim, Oliver Richard L. Assessing the dimensionality and structure

of the consumption experience: evaluation, feeling, and satisfaction. J

Consum Res 1993;20(3):451 – 66.

Mehrabian Albert, Russell James A. An approach to environmental

psychology. Cambridge, MA7 MIT Press; 1974.

Morgan Rich L., Heise David. Structure of emotions. Soc Psychol Q

1988;51(1):19 – 31.

Netemeyer Richard G, Durvasula Srinivas, Lichtenstein Donald. A crossnational assessment of the reliability and validity of the CETSCALE. J

Mark Res 1991;28(3):320 – 7.

Nyer Prashanth U. A study of the relationships between cognitive

appraisals and consumption emotions. J Acad Mark Sci 1997;25(4):

296 – 304.

Oliver Richard L. Cognitive, affective, and attribute bases of the satisfaction

response. J Consum Res 1993;20(3):418 – 30.

Olney Thomas J, Holbrook Morris B., Batra Rajeev. Consumer responses to

advertising: the effects of ad content, emotions, and attitude toward the

ad on viewing time. J Consum Res 1991;17(4):440 – 53.

Ortony Andrew, Turner Terence J. What’s basic about basic emotions?

Psychol Rev 1990;97(3):315 – 31.

Panksepp Jaak. A crititical role for baffective neuroscienceQ in resolving

what is basic about basic emotions. Psychol Rev 1992;99(3):554 – 60.

Phillips Diane M, Baumgartner Hans. The role of consumption emotions in

the satisfaction response. J Consum Psychol 2002;12(3):243 – 52.

Plutchik Robert. Emotion: a psychoevolutionary synthesis. New York7

Harper and Row; 1980.

Richins Marsha L. Measuring emotions in the consumption experience. J

Consum Res 1997;24(2):127 – 46.

Richins Marsha L, Dawson Scott. A consumer values orientation for

materialism and its measurement: measure development and validation.

J Consum Res 1992;19(3):303 – 16.

Roseman Ira J, Antoniou Ann A, Jose Paul J. Appraisal determinants of

emotions: constructing a more accurate and comprehensive theory.

Cogn Emot 1996;10(3):241 – 77.

Russell James A., Weiss A., Mendelsohn G.A.. Affect grid - A single-item

scale of pleasure and arousal. J Pers Soc Psychol 1989;57(3):493 – 502.

Russell James A. A circumplex model of affect. J Pers Soc Psychol 1980;

39(6):1161 – 78.

Ruth Julie A, Brunel Frederic F, Otnes Cele C. Linking thoughts to feelings:

investigating cognitive appraisals and consumption emotions in a

mixed-emotions context. J Acad Mark Sci 2002;30(1):44 – 58.

1445

Shaver Philip, Schwartz Judith, Kirson Donald, O’Conner Cary. Emotion

knowledge: further exploration of a prototype approach. J Pers Soc

Psychol 1987;52:1061 – 86.

Smith Amy K, Bolton Ruth N. The effects of customers’ emotional

responses to service failures on their recovery effort evaluations and

satisfaction judgments. J Acad Mark Sci 2002;30(1):5 – 23.

Smith Craig A, Lazarus Richard S. Appraisal components, core relational

themes, and emotions. Cogn Emot 1993;7:295 – 323.

Steenkamp Jan-Benedict EM, Baumgartner Hans. Assessing measurement

invariance in cross-national consumer research. J Consum Res 1998;

25(1):78 – 90.

Steenkamp Jan-Benedict E.M., Burgess Steven M.. Optimum stimulation

level and exploratory consumer behavior in an emerging consumer

market. Int J Res Mark 2002;19:131 – 50.

Steenkamp Jan-Benedict EM, Van Trijp Hans CM. The use of LISREL in

validating marketing constructs. Int J Res Mark 1991;8(4):283 – 99.

Steenkamp Jan-Benedict EM, Baumgartner Hans, Van der Wulp Elise. The

relationships among arousal potential, arousal and stimulus evaluation,

and the moderating role of need for stimulation. Int J Res Mark

1996;13:319 – 29.

Stephens Nancy, Gwinner Kevin P. Why don’t some people complain? A

cognitive–emotive process model of consumer complaint behavior. J

Acad Mark Sci 1998;26(4):172 – 89.

Storm Christine, Storm Tom. A taxonomic study of the vocabulary of

emotions. J Pers Soc Psychol 1987;53:805 – 16.

Taylor Shirley. Waiting for service: the relationship between delays and

evaluations of service. J Mark 1994;58(2):56 – 69.

Tsiros Michael, Mittal Vikas. Regret: a model of its antecedents and

consequences in consumer decision making. J Consum Res

2000;26(4):401 – 17.

Turner Terence J, Ortony Andrew. Basic emotions: can conflicting criteria

converge? Psychol Rev 1992;99(3):566 – 71.

Verbeke Willem, Bagozzi Richard P. Exploring the role of self- and

customer-provoked embarrassment in personal selling. Int J Res Mark

2003;20:233 – 58.

Watson David, Tellegen Auke. Toward a consensual structure of mood.

Psychol Bull 1985;98:219 – 35.

Watson David, Clark Lee Anna, Tellegen Auke. Development and

validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS

scales. J Pers Soc Psychol 1988;54:1063 – 70.

Watson David, Wiese David, Vaidya Jatin, Tellegen Auke. The two general

activation systems of affect: structural findings, evolutionary considerations, and psychobiological evidence. J Pers Soc Psychol 1999;

76(5):820 – 38.

Westbrook Robert A. Product/consumption-based affective responses and

post-purchase processes. J Mark Res 1987;24:258 – 70.

Wong Nancy, Rindfleisch Aric, Burroughs James E. Do reverse-worded

items confound measures in cross-cultural consumer research: the case

of the material values scale. J Consum Res 2003;30(1):72 – 91.

Zeelenberg Marcel, Pieters Rik. Comparing service delivery to what might

have been. J Serv Res 1999;2(1):86 – 97.

Zeelenberg Marcel, Van Dijk Wilco W, Manstead Antony SR, Van der Pligt

Joop. The experience of regret and disappointment. Cogn Emot

1998;12(2):221 – 30.

�