eSignature Legality for Public Relations in United Kingdom with airSlate SignNow

- Quick to start

- Easy-to-use

- 24/7 support

Simplified document journeys for small teams and individuals

We spread the word about digital transformation

Why choose airSlate SignNow

-

Free 7-day trial. Choose the plan you need and try it risk-free.

-

Honest pricing for full-featured plans. airSlate SignNow offers subscription plans with no overages or hidden fees at renewal.

-

Enterprise-grade security. airSlate SignNow helps you comply with global security standards.

What is the e signature legality for public relations in united kingdom

The legality of eSignatures in the United Kingdom is established under the Electronic Communications Act 2000 and the EU's eIDAS Regulation, which recognizes electronic signatures as having the same legal standing as traditional handwritten signatures. This means that eSignatures can be used in public relations documents, such as contracts, agreements, and consent forms, provided they meet certain criteria. The key requirement is that the signatory must have the intent to sign, which can be demonstrated through various methods, including clicking an “I agree” button or using a stylus on a touchscreen device.

How to use the e signature legality for public relations in united kingdom

Using eSignatures in public relations involves several steps. First, ensure that the document is suitable for eSigning, which typically includes contracts and agreements. Next, upload the document to a secure eSignature platform like airSlate SignNow. You can then specify where signatures are needed and send the document to the relevant parties for their signatures. Once signed, the document is securely stored and can be shared with stakeholders, ensuring compliance with legal standards.

Steps to complete the e signature legality for public relations in united kingdom

Completing an eSignature process for public relations documents is straightforward. Follow these steps:

- Prepare the document by ensuring it is in an acceptable format, such as PDF or Word.

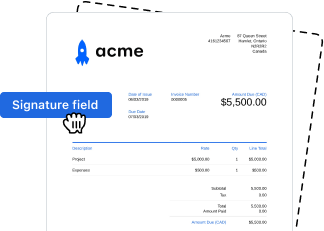

- Upload the document to airSlate SignNow and designate the areas where signatures are required.

- Enter the email addresses of the signatories to send the document for signature.

- Notify the recipients to review and sign the document electronically.

- Once all parties have signed, download the completed document for your records.

Key elements of the e signature legality for public relations in united kingdom

Several key elements contribute to the legality of eSignatures in public relations. These include:

- Intent to sign: The signatory must demonstrate a clear intention to sign the document.

- Consent: All parties involved must agree to use electronic signatures.

- Security: The eSignature process must ensure the integrity and authenticity of the signed document.

- Record-keeping: It is essential to maintain a secure and accessible record of the signed document.

Legal use of the e signature legality for public relations in united kingdom

In the context of public relations, eSignatures can be legally used for a variety of documents, including contracts, non-disclosure agreements, and client consent forms. To ensure legal compliance, organizations must adhere to the requirements outlined in the Electronic Communications Act and the eIDAS Regulation. This includes verifying the identity of signatories and ensuring that the eSignature method used is secure and reliable.

Security & Compliance Guidelines

When utilizing eSignatures in public relations, it is crucial to follow security and compliance guidelines. Ensure that the eSignature platform you choose, like airSlate SignNow, employs robust encryption methods to protect sensitive information. Additionally, implement access controls to limit who can view and sign documents. Regular audits and compliance checks can help maintain adherence to legal standards and protect against potential fraud.

-

Best ROI. Our customers achieve an average 7x ROI within the first six months.

-

Scales with your use cases. From SMBs to mid-market, airSlate SignNow delivers results for businesses of all sizes.

-

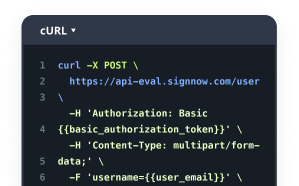

Intuitive UI and API. Sign and send documents from your apps in minutes.

FAQs

-

What is the e signature legality for public relations in the United Kingdom?

In the United Kingdom, e signatures are legally recognized under the Electronic Communications Act 2000 and the eIDAS Regulation. This means that e signatures can be used for public relations documents, provided they meet certain criteria. It's essential to ensure that the e signature method used is secure and verifiable to comply with legal standards.

-

How does airSlate SignNow ensure compliance with e signature legality for public relations in the United Kingdom?

airSlate SignNow complies with the e signature legality for public relations in the United Kingdom by utilizing advanced encryption and authentication methods. Our platform provides a secure environment for signing documents, ensuring that all signatures are legally binding and meet UK regulations. This gives businesses peace of mind when managing their public relations documents.

-

What features does airSlate SignNow offer for managing e signatures in public relations?

airSlate SignNow offers a range of features tailored for public relations, including customizable templates, real-time tracking, and automated reminders. These features streamline the signing process, making it easier to manage multiple documents efficiently. By leveraging these tools, businesses can enhance their public relations efforts while ensuring e signature legality for public relations in the United Kingdom.

-

Is airSlate SignNow cost-effective for public relations teams?

Yes, airSlate SignNow is designed to be a cost-effective solution for public relations teams. Our pricing plans are flexible and cater to businesses of all sizes, allowing teams to choose a plan that fits their budget. By investing in airSlate SignNow, public relations teams can save time and resources while ensuring compliance with e signature legality for public relations in the United Kingdom.

-

Can airSlate SignNow integrate with other tools used in public relations?

Absolutely! airSlate SignNow offers seamless integrations with various tools commonly used in public relations, such as CRM systems, project management software, and email platforms. These integrations enhance workflow efficiency and ensure that all documents signed electronically comply with e signature legality for public relations in the United Kingdom.

-

What are the benefits of using airSlate SignNow for public relations?

Using airSlate SignNow for public relations provides numerous benefits, including faster document turnaround times, improved collaboration, and enhanced security. By adopting our e signature solution, public relations teams can focus on their core activities while ensuring that all signed documents adhere to e signature legality for public relations in the United Kingdom.

-

How does airSlate SignNow handle document security for e signatures?

airSlate SignNow prioritizes document security by employing industry-standard encryption and secure storage solutions. This ensures that all documents signed electronically are protected from unauthorized access. By maintaining high security standards, we help businesses comply with e signature legality for public relations in the United Kingdom.