Unlock eSignature Legitimacy for Pregnancy Leave Policy in United States

- Quick to start

- Easy-to-use

- 24/7 support

Simplified document journeys for small teams and individuals

We spread the word about digital transformation

Why choose airSlate SignNow

-

Free 7-day trial. Choose the plan you need and try it risk-free.

-

Honest pricing for full-featured plans. airSlate SignNow offers subscription plans with no overages or hidden fees at renewal.

-

Enterprise-grade security. airSlate SignNow helps you comply with global security standards.

Your complete how-to guide - e signature licitness for pregnancy leave policy in united states

eSignature Licitness for Pregnancy Leave Policy in United States

When it comes to implementing an eSignature licitness for Pregnancy Leave Policy in the United States, airSlate SignNow is a reliable solution. By following a few simple steps, you can quickly set up and send eSignature invites for your important documents.

Step-by-step Guide:

- Launch the airSlate SignNow web page in your browser.

- Sign up for a free trial or log in.

- Upload a document you want to sign or send for signing.

- If you're going to reuse your document later, turn it into a template.

- Open your file and make edits: add fillable fields or insert information.

- Sign your document and add signature fields for the recipients.

- Click Continue to set up and send an eSignature invite.

airSlate SignNow empowers businesses to send and eSign documents with an easy-to-use, cost-effective solution. It provides a great ROI, is easy to use and scale, tailored for SMBs, and Mid-Market, has transparent pricing with no hidden support fees or add-on costs, and offers superior 24/7 support for all paid plans.

Experience the benefits of airSlate SignNow today and streamline your document signing process!

How it works

Rate your experience

What is the e signature licitness for pregnancy leave policy in united states

The e signature licitness for pregnancy leave policy in the United States refers to the legal acceptance of electronic signatures on documents related to pregnancy leave. This includes forms that employees submit to request maternity leave, as well as any supporting documentation required by employers. Under the Electronic Signatures in Global and National Commerce Act (ESIGN) and the Uniform Electronic Transactions Act (UETA), electronic signatures hold the same legal weight as traditional handwritten signatures, provided that both parties consent to use electronic means for signing.

How to use the e signature licitness for pregnancy leave policy in united states

To effectively use the e signature licitness for pregnancy leave policy, employees can complete their leave request forms electronically. This process typically involves filling out the necessary fields in the document, which may include personal information, expected leave dates, and any required documentation. Once completed, users can eSign the document using airSlate SignNow, ensuring that their signature is securely captured and legally binding. Employers can then review, approve, and store these documents electronically, streamlining the entire process.

Steps to complete the e signature licitness for pregnancy leave policy in united states

Completing the e signature licitness for pregnancy leave policy involves several straightforward steps:

- Access the pregnancy leave policy form through your employer's designated platform.

- Fill in all required fields, providing accurate and relevant information.

- Review the document to ensure all details are correct.

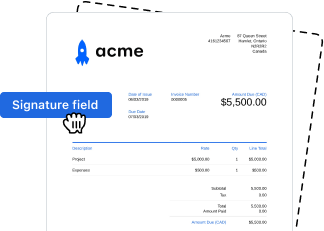

- Use airSlate SignNow to eSign the document by clicking on the designated signature field.

- Submit the completed form electronically for review by your employer.

This process not only saves time but also ensures that all documentation is stored securely and is easily accessible for future reference.

Legal use of the e signature licitness for pregnancy leave policy in united states

The legal use of e signatures in the context of pregnancy leave policies is supported by federal and state laws that recognize electronic signatures as valid. Employers must ensure that their policies comply with these regulations, which require that employees have the option to opt-in to electronic signing. Additionally, the process must maintain the integrity of the document, ensuring that it cannot be altered after signing. This legal framework provides both employees and employers with confidence in the validity of electronically signed documents.

Key elements of the e signature licitness for pregnancy leave policy in united states

Key elements of the e signature licitness for pregnancy leave policy include:

- Consent: Both parties must agree to use electronic signatures.

- Authentication: Measures should be in place to verify the identity of the signer.

- Integrity: The document must remain unaltered after signing.

- Record-keeping: Employers must maintain electronic records of signed documents for compliance purposes.

These elements ensure that the e signature process is secure, reliable, and legally binding.

State-specific rules for the e signature licitness for pregnancy leave policy in united states

While federal laws provide a general framework for e signatures, individual states may have specific regulations that affect their use in pregnancy leave policies. For instance, some states may require additional disclosures or have unique consent requirements. It is essential for both employees and employers to be aware of their state's laws regarding electronic signatures to ensure compliance. Consulting with legal counsel or human resources can help clarify any state-specific requirements.

-

Best ROI. Our customers achieve an average 7x ROI within the first six months.

-

Scales with your use cases. From SMBs to mid-market, airSlate SignNow delivers results for businesses of all sizes.

-

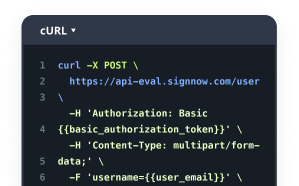

Intuitive UI and API. Sign and send documents from your apps in minutes.

FAQs

-

What is the e signature licitness for pregnancy leave policy in the United States?

The e signature licitness for pregnancy leave policy in the United States refers to the legal acceptance of electronic signatures on documents related to pregnancy leave. This means that employers can use e signatures to streamline the process of submitting and approving leave requests, ensuring compliance with federal and state regulations.

-

How does airSlate SignNow ensure compliance with e signature licitness for pregnancy leave policy in the United States?

airSlate SignNow complies with the e signature licitness for pregnancy leave policy in the United States by adhering to the ESIGN Act and UETA regulations. Our platform provides secure, legally binding electronic signatures that meet all necessary legal standards, ensuring that your pregnancy leave documents are valid and enforceable.

-

What features does airSlate SignNow offer for managing pregnancy leave documents?

airSlate SignNow offers a range of features for managing pregnancy leave documents, including customizable templates, automated workflows, and real-time tracking. These tools help streamline the process of obtaining e signatures, making it easier for both employees and HR departments to manage leave requests efficiently.

-

Is airSlate SignNow cost-effective for small businesses handling pregnancy leave policies?

Yes, airSlate SignNow is a cost-effective solution for small businesses managing pregnancy leave policies. Our pricing plans are designed to accommodate businesses of all sizes, allowing you to implement e signature solutions without breaking the bank while ensuring compliance with e signature licitness for pregnancy leave policy in the United States.

-

Can airSlate SignNow integrate with other HR software for managing pregnancy leave?

Absolutely! airSlate SignNow can seamlessly integrate with various HR software systems, enhancing your ability to manage pregnancy leave policies. This integration allows for a smoother workflow, ensuring that all documents are processed efficiently while maintaining compliance with e signature licitness for pregnancy leave policy in the United States.

-

What are the benefits of using e signatures for pregnancy leave documentation?

Using e signatures for pregnancy leave documentation offers numerous benefits, including faster processing times, reduced paperwork, and enhanced security. By leveraging airSlate SignNow, businesses can ensure that their processes align with the e signature licitness for pregnancy leave policy in the United States, making it easier for employees to submit requests.

-

How secure is airSlate SignNow for handling sensitive pregnancy leave documents?

airSlate SignNow prioritizes security by employing advanced encryption and authentication measures to protect sensitive pregnancy leave documents. Our platform ensures that all e signatures are legally binding and compliant with the e signature licitness for pregnancy leave policy in the United States, providing peace of mind for both employers and employees.

Related searches to e signature licitness for pregnancy leave policy in united states

Join over 28 million airSlate SignNow users

Get more for e signature licitness for pregnancy leave policy in united states

- ESignature Licitness for Procurement in Canada: ...

- ESignature Licitness for Procurement in the European ...

- ESignature Licitness for Procurement in UAE

- ESignature Licitness for Procurement in India: ...

- ESignature Legality Boosts Procurement Efficiency in ...

- ESignature Licitness for Product Management in ...

- ESignature Licitness for Product Management in Mexico

- ESignature Licitness for Product Management in United ...