Unlock the Power of Electronic Signature Legality for Assignment of Intellectual Property in Canada

- Quick to start

- Easy-to-use

- 24/7 support

Simplified document journeys for small teams and individuals

We spread the word about digital transformation

Why choose airSlate SignNow

-

Free 7-day trial. Choose the plan you need and try it risk-free.

-

Honest pricing for full-featured plans. airSlate SignNow offers subscription plans with no overages or hidden fees at renewal.

-

Enterprise-grade security. airSlate SignNow helps you comply with global security standards.

Your complete how-to guide - electronic signature legality for assignment of intellectual property in canada

Electronic Signature Legality for Assignment of Intellectual Property in Canada

When dealing with the assignment of intellectual property in Canada, it is essential to ensure that all documents are properly signed and legally binding. One efficient way to do this is by using electronic signatures, which are recognized as valid in Canada. By leveraging a trusted platform like airSlate SignNow, businesses can streamline the signing process and eliminate the need for physical signatures.

Steps to Utilize airSlate SignNow for Electronic Signature

- Launch the airSlate SignNow web page in your browser.

- Sign up for a free trial or log in.

- Upload a document you want to sign or send for signing.

- Convert your document into a template for future use.

- Edit your file by adding fillable fields or necessary information.

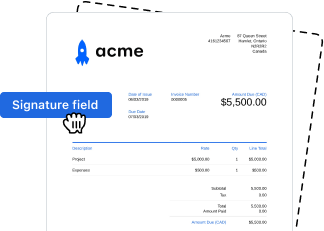

- Add your signature and recipient signature fields.

- Click Continue to configure and send the eSignature request.

airSlate SignNow offers an easy-to-use and cost-effective solution for businesses looking to streamline their document signing processes. With features tailored for SMBs and Mid-Market organizations, it provides great ROI by offering a rich feature set at an affordable price. Additionally, the platform's transparent pricing, combined with superior 24/7 support on all paid plans, makes it a reliable choice for businesses of all sizes.

Experience the benefits of airSlate SignNow today and revolutionize the way you handle document signing processes!

How it works

Rate your experience

Understanding electronic signature legality for assignment of intellectual property in Canada

The legality of electronic signatures for the assignment of intellectual property in Canada is supported by the Uniform Electronic Commerce Act (UECA) and the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA). These laws establish that electronic signatures hold the same legal weight as traditional handwritten signatures, provided they meet certain criteria. This includes the intent to sign, consent to use electronic means, and the ability to retain a copy of the signed document. Understanding these legal frameworks is essential for ensuring that your electronic signatures are valid and enforceable in the context of intellectual property assignments.

Steps to complete the electronic signature process for assignment of intellectual property

Completing the assignment of intellectual property using electronic signatures involves several straightforward steps:

- Prepare the document that outlines the terms of the intellectual property assignment.

- Upload the document to airSlate SignNow, ensuring it is in a compatible format.

- Use the fill and sign feature to complete any necessary fields within the document.

- Send the document for signature to the relevant parties via email, using airSlate SignNow’s secure sharing options.

- Once all parties have signed, the completed document will be stored securely in your airSlate SignNow account for future reference.

Legal use of electronic signatures in intellectual property assignments

To ensure the legal use of electronic signatures in intellectual property assignments, it is crucial to adhere to the following guidelines:

- Ensure all parties involved consent to the use of electronic signatures.

- Maintain a clear audit trail that records the signing process, including timestamps and IP addresses.

- Provide access to a copy of the signed document to all parties involved.

- Utilize a reputable eSignature solution like airSlate SignNow that complies with relevant legal standards.

Security and compliance guidelines for electronic signatures

When using electronic signatures for the assignment of intellectual property, security and compliance are paramount. Here are key practices to follow:

- Use strong authentication methods to verify the identity of signers.

- Ensure that the document is encrypted during transmission and storage.

- Regularly review and update security protocols to protect sensitive information.

- Stay informed about changes in legislation regarding electronic signatures to ensure ongoing compliance.

Examples of using electronic signatures for intellectual property assignments

Electronic signatures can be effectively utilized in various scenarios involving intellectual property assignments, such as:

- Assigning copyrights for creative works, like music or literature.

- Transferring patent rights between inventors or companies.

- Licensing agreements where electronic signatures streamline the approval process.

Timeframes and processing delays in electronic signature workflows

Understanding the timeframes associated with electronic signature workflows can help manage expectations. Generally, the signing process can be completed within minutes to hours, depending on the number of signers and their availability. However, factors such as document complexity and the need for additional approvals may introduce delays. Using airSlate SignNow can help minimize these delays through efficient document management and notifications.

-

Best ROI. Our customers achieve an average 7x ROI within the first six months.

-

Scales with your use cases. From SMBs to mid-market, airSlate SignNow delivers results for businesses of all sizes.

-

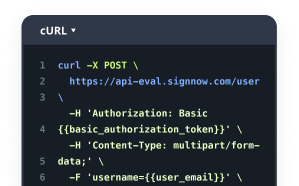

Intuitive UI and API. Sign and send documents from your apps in minutes.

FAQs

-

What is the electronic signature legality for assignment of intellectual property in Canada?

In Canada, electronic signatures are legally recognized under the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) and various provincial laws. This means that electronic signatures can be used for the assignment of intellectual property, provided they meet certain criteria for authenticity and integrity.

-

How does airSlate SignNow ensure compliance with electronic signature legality for assignment of intellectual property in Canada?

airSlate SignNow complies with Canadian laws regarding electronic signatures by implementing robust security measures and authentication processes. Our platform ensures that all signed documents are legally binding and can be used for the assignment of intellectual property in Canada.

-

What features does airSlate SignNow offer for managing electronic signatures?

airSlate SignNow offers a variety of features including customizable templates, real-time tracking, and secure storage. These features enhance the electronic signature legality for assignment of intellectual property in Canada, making it easier for businesses to manage their documents efficiently.

-

Is airSlate SignNow a cost-effective solution for electronic signatures?

Yes, airSlate SignNow is designed to be a cost-effective solution for businesses of all sizes. Our pricing plans are competitive, ensuring that you can utilize electronic signature legality for assignment of intellectual property in Canada without breaking the bank.

-

Can airSlate SignNow integrate with other software tools?

Absolutely! airSlate SignNow offers seamless integrations with various software tools such as CRM systems, cloud storage, and project management applications. This enhances the electronic signature legality for assignment of intellectual property in Canada by streamlining your workflow.

-

What are the benefits of using electronic signatures for intellectual property assignments?

Using electronic signatures for intellectual property assignments offers numerous benefits, including faster turnaround times, reduced paperwork, and enhanced security. This aligns with the electronic signature legality for assignment of intellectual property in Canada, ensuring that your agreements are both efficient and legally binding.

-

How secure is airSlate SignNow for electronic signatures?

airSlate SignNow prioritizes security with advanced encryption and authentication protocols. This ensures that your electronic signatures are secure and compliant with the electronic signature legality for assignment of intellectual property in Canada, protecting your sensitive information.