Unlocking eSignature Legality for Higher Education in Australia

- Quick to start

- Easy-to-use

- 24/7 support

Simplified document journeys for small teams and individuals

We spread the word about digital transformation

Why choose airSlate SignNow

-

Free 7-day trial. Choose the plan you need and try it risk-free.

-

Honest pricing for full-featured plans. airSlate SignNow offers subscription plans with no overages or hidden fees at renewal.

-

Enterprise-grade security. airSlate SignNow helps you comply with global security standards.

Your complete how-to guide - esignature legality for higher education in australia

eSignature Legality for Higher Education in Australia

In the digital age, eSignatures are becoming increasingly popular for their convenience and efficiency. When it comes to Higher Education in Australia, ensuring the legality of eSignatures is crucial. This guide will walk you through using airSlate SignNow to streamline your document signing process while adhering to Australian legal requirements.

How to Use airSlate SignNow for eSigning Documents:

- Launch the airSlate SignNow web page in your browser.

- Sign up for a free trial or log in.

- Upload a document you want to sign or send for signing.

- If you're going to reuse your document later, turn it into a template.

- Open your file and make edits: add fillable fields or insert information.

- Sign your document and add signature fields for the recipients.

- Click Continue to set up and send an eSignature invite.

airSlate SignNow empowers businesses to send and eSign documents with an easy-to-use, cost-effective solution. It offers great ROI with a rich feature set, is tailored for SMBs and Mid-Market, has transparent pricing without hidden fees, and provides superior 24/7 support for all paid plans.

Experience the benefits of airSlate SignNow today and streamline your document signing process with ease!

How it works

Rate your experience

What is the esignature legality for higher education in australia

The legality of electronic signatures in higher education in Australia is governed by the Electronic Transactions Act 1999 and the Australian Consumer Law. These laws establish that electronic signatures hold the same legal weight as traditional handwritten signatures, provided certain conditions are met. This includes the requirement that the signatory intends to sign the document and that the signature is linked to the document in a way that allows for its integrity to be maintained. Institutions in Australia can confidently adopt eSignatures for various documents, including enrollment forms, contracts, and consent forms, ensuring a streamlined process for students and administrators alike.

Steps to complete the esignature legality for higher education in australia

To effectively utilize eSignatures within the higher education sector, follow these steps:

- Choose a reliable eSignature platform, such as airSlate SignNow, that complies with Australian laws.

- Upload the document that requires signatures.

- Specify the areas where signatures are needed, including any additional fields for information.

- Send the document to the intended signatories via email or a secure link.

- Notify signatories to review and sign the document electronically.

- Once all parties have signed, the completed document is securely stored and can be accessed anytime.

Security & Compliance Guidelines

Ensuring the security and compliance of eSignatures in higher education is critical. Institutions should adhere to the following guidelines:

- Use encryption to protect documents during transmission and storage.

- Implement multi-factor authentication to verify the identity of signatories.

- Maintain audit trails that log every action taken on the document, including when it was sent, viewed, and signed.

- Regularly review and update security protocols to address emerging threats.

By following these guidelines, educational institutions can safeguard sensitive information while complying with legal standards.

Examples of using the esignature legality for higher education in australia

eSignatures can be applied in various scenarios within higher education, including:

- Enrollment forms: Students can electronically sign their enrollment documents, simplifying the registration process.

- Financial aid applications: eSignatures streamline the submission of applications for scholarships and grants.

- Course registration: Students can quickly sign up for classes without the need for physical paperwork.

- Consent forms: Institutions can obtain electronic consent for various activities, such as research participation or medical treatment.

These examples illustrate how eSignatures enhance efficiency and accessibility in administrative processes.

Digital vs. Paper-Based Signing

Choosing between digital and paper-based signing methods can significantly impact operational efficiency in higher education. Digital signing offers several advantages:

- Speed: eSignatures reduce the time taken to complete documents, allowing for quicker processing.

- Cost-effectiveness: Reducing paper usage leads to lower printing and storage costs.

- Accessibility: Students and staff can sign documents from anywhere, using any device with internet access.

- Environmental impact: Digital processes contribute to sustainability efforts by minimizing paper waste.

These benefits make digital signing a compelling choice for educational institutions looking to modernize their workflows.

Eligibility and Access to esignature legality for higher education in australia

All individuals involved in higher education, including students, faculty, and administrative staff, are eligible to use eSignatures. To access eSignature capabilities, institutions must ensure:

- Compliance with relevant laws and regulations regarding electronic transactions.

- A reliable eSignature platform that meets security and legal standards.

- Training and resources for users to understand how to effectively use eSignatures.

By fostering an inclusive environment, institutions can enhance participation in digital workflows.

-

Best ROI. Our customers achieve an average 7x ROI within the first six months.

-

Scales with your use cases. From SMBs to mid-market, airSlate SignNow delivers results for businesses of all sizes.

-

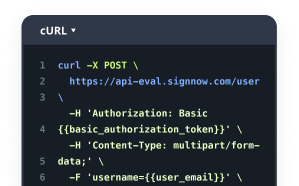

Intuitive UI and API. Sign and send documents from your apps in minutes.

FAQs

-

What is the esignature legality for higher education in Australia?

The esignature legality for higher education in Australia is governed by the Electronic Transactions Act 1999, which recognizes electronic signatures as legally binding. This means that institutions can use esignatures for various documents, including enrollment forms and contracts, ensuring compliance with Australian law.

-

How does airSlate SignNow ensure compliance with esignature legality for higher education in Australia?

airSlate SignNow adheres to the Electronic Transactions Act, providing a secure platform for esignatures that meets legal standards. Our solution includes features like audit trails and authentication methods to ensure that all signed documents are valid and enforceable in Australia.

-

What are the benefits of using airSlate SignNow for esignatures in higher education?

Using airSlate SignNow for esignatures in higher education streamlines the document signing process, saving time and resources. It enhances the student experience by allowing quick and easy access to necessary forms while ensuring compliance with esignature legality for higher education in Australia.

-

Can airSlate SignNow integrate with existing systems in higher education institutions?

Yes, airSlate SignNow offers seamless integrations with various systems commonly used in higher education, such as student information systems and learning management platforms. This ensures that institutions can easily incorporate esignature functionality into their existing workflows while maintaining compliance with esignature legality for higher education in Australia.

-

What types of documents can be signed electronically using airSlate SignNow?

airSlate SignNow allows for the electronic signing of a wide range of documents, including admission forms, contracts, and policy agreements. This versatility supports the esignature legality for higher education in Australia, making it easier for institutions to manage their documentation efficiently.

-

Is airSlate SignNow cost-effective for higher education institutions?

Yes, airSlate SignNow is designed to be a cost-effective solution for higher education institutions. With flexible pricing plans, institutions can choose the option that best fits their budget while benefiting from the legal assurance of esignature legality for higher education in Australia.

-

How secure is the esignature process with airSlate SignNow?

The esignature process with airSlate SignNow is highly secure, utilizing encryption and secure storage to protect sensitive information. This commitment to security ensures that all signed documents comply with esignature legality for higher education in Australia, providing peace of mind for institutions and their students.

Related searches to esignature legality for higher education in australia

Join over 28 million airSlate SignNow users

Get more for esignature legality for higher education in australia

- Easily insert signature field in Google Docs with ...

- Put electronic signature in Excel seamlessly for your ...

- Easily insert signature in pages file with airSlate ...

- Inserting a signature in pages made easy with airSlate ...

- Place signature files effortlessly with airSlate ...

- Putting a signature on a document made simple