Unlock eSignature Legitimacy in the European Union Tech Industry

- Quick to start

- Easy-to-use

- 24/7 support

Simplified document journeys for small teams and individuals

We spread the word about digital transformation

Why choose airSlate SignNow

-

Free 7-day trial. Choose the plan you need and try it risk-free.

-

Honest pricing for full-featured plans. airSlate SignNow offers subscription plans with no overages or hidden fees at renewal.

-

Enterprise-grade security. airSlate SignNow helps you comply with global security standards.

Your complete how-to guide - esignature legitimacy for technology industry in european union

eSignature Legitimacy for Technology Industry in European Union

The use of eSignatures has gained signNow traction in the Technology Industry within the European Union. To ensure the legitimacy of electronic signatures, businesses can leverage airSlate SignNow, a trusted solution that complies with all necessary regulations and standards.

Steps to Utilize airSlate SignNow:

- Launch the airSlate SignNow web page in your browser.

- Sign up for a free trial or log in.

- Upload a document you want to sign or send for signing.

- If you're going to reuse your document later, turn it into a template.

- Open your file and make edits: add fillable fields or insert information.

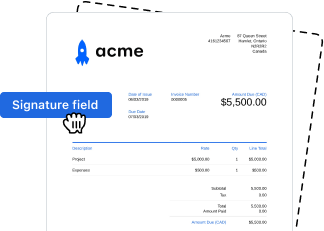

- Sign your document and add signature fields for the recipients.

- Click Continue to set up and send an eSignature invite.

airSlate SignNow empowers businesses to send and eSign documents with an easy-to-use, cost-effective solution. With great ROI, tailored features for SMBs and Mid-Market, transparent pricing, and superior 24/7 support for all paid plans, it offers a comprehensive solution for electronic signatures in the Technology Industry.

Experience the benefits of airSlate SignNow today and streamline your document signing processes effortlessly!

How it works

Rate your experience

Understanding eSignature Legitimacy in the Technology Industry

The legitimacy of eSignatures in the technology industry within the European Union is established through regulations such as the eIDAS Regulation. This framework ensures that electronic signatures have the same legal standing as traditional handwritten signatures. It is essential for businesses to recognize that eSignatures are valid for a wide range of documents, including contracts, agreements, and other legal forms. This recognition facilitates smoother transactions and enhances operational efficiency.

How to Use eSignature Legitimacy in the Technology Industry

To effectively utilize eSignature legitimacy, businesses should first ensure compliance with eIDAS regulations. This involves selecting a qualified trust service provider that meets the necessary standards for electronic signatures. Once compliant, users can create, send, and manage documents electronically using airSlate SignNow. The process typically includes uploading a document, specifying signers, and sending it for signature. This streamlines workflows and reduces the time spent on paper-based processes.

Steps to Complete eSignature Processes

Completing an eSignature process involves several straightforward steps:

- Upload the document you wish to sign.

- Specify the recipients who need to sign the document.

- Place signature fields where necessary.

- Send the document for signature.

- Receive notifications as signers complete their actions.

- Download the signed document for your records.

This method ensures that all parties can easily access and complete the signing process, enhancing collaboration and efficiency.

Legal Use of eSignatures in the Technology Industry

eSignatures are legally binding in many jurisdictions, including the European Union, provided they comply with the eIDAS Regulation. Businesses must ensure that their eSignature practices adhere to these legal standards to avoid disputes. It is advisable to maintain a clear audit trail, documenting the signing process and any associated communications. This documentation serves as proof of consent and can be crucial in legal scenarios.

Key Elements of eSignature Legitimacy

Several key elements contribute to the legitimacy of eSignatures in the technology sector:

- Authentication: Verifying the identity of signers is crucial.

- Integrity: Ensuring that the document has not been altered after signing.

- Non-repudiation: Providing evidence that a signer cannot deny having signed the document.

- Compliance: Adhering to relevant regulations and standards.

By focusing on these elements, businesses can enhance the trustworthiness of their electronic signing processes.

Security and Compliance Guidelines for eSignatures

Security is paramount when dealing with eSignatures. Organizations should implement robust security measures, such as encryption and secure access controls, to protect sensitive information. Compliance with data protection regulations, such as GDPR, is also essential. Regular audits and assessments can help identify potential vulnerabilities and ensure that eSignature practices remain compliant with legal standards.

-

Best ROI. Our customers achieve an average 7x ROI within the first six months.

-

Scales with your use cases. From SMBs to mid-market, airSlate SignNow delivers results for businesses of all sizes.

-

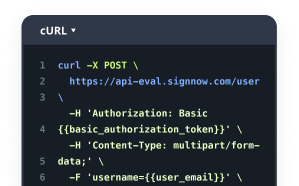

Intuitive UI and API. Sign and send documents from your apps in minutes.

FAQs

-

What is the importance of esignature legitimacy for technology industry in European Union?

Esignature legitimacy for technology industry in European Union is crucial as it ensures that electronic signatures are legally recognized and enforceable. This legitimacy helps businesses streamline their operations while maintaining compliance with EU regulations. By adopting esignatures, companies can enhance their efficiency and reduce the risk of legal disputes.

-

How does airSlate SignNow ensure esignature legitimacy for technology industry in European Union?

airSlate SignNow complies with the eIDAS regulation, which governs electronic signatures in the European Union. This compliance guarantees that all esignatures created using our platform are legally binding and secure. Our solution provides users with the confidence that their documents meet the necessary legal standards.

-

What features does airSlate SignNow offer to support esignature legitimacy for technology industry in European Union?

airSlate SignNow offers features such as secure document storage, audit trails, and customizable workflows that enhance esignature legitimacy for technology industry in European Union. These features ensure that every signature is traceable and verifiable, providing an additional layer of security. Users can also integrate advanced authentication methods to further validate signers.

-

Is airSlate SignNow cost-effective for businesses in the technology industry?

Yes, airSlate SignNow is a cost-effective solution for businesses in the technology industry looking to implement esignature legitimacy for technology industry in European Union. Our pricing plans are designed to accommodate various business sizes and needs, ensuring that companies can access essential features without breaking the bank. This affordability allows businesses to invest in digital transformation confidently.

-

Can airSlate SignNow integrate with other tools used in the technology industry?

Absolutely! airSlate SignNow offers seamless integrations with popular tools and platforms commonly used in the technology industry. This capability enhances esignature legitimacy for technology industry in European Union by allowing businesses to incorporate esignatures into their existing workflows. Integrations with CRM, project management, and document management systems streamline processes and improve efficiency.

-

What are the benefits of using airSlate SignNow for esignature legitimacy in the technology sector?

Using airSlate SignNow for esignature legitimacy in the technology sector provides numerous benefits, including increased efficiency, reduced paper usage, and enhanced security. Businesses can quickly send and sign documents, accelerating transaction times and improving customer satisfaction. Additionally, our platform ensures compliance with legal standards, safeguarding your business against potential risks.

-

How does airSlate SignNow handle data security for esignatures?

airSlate SignNow prioritizes data security by employing advanced encryption methods and secure data storage practices. This commitment to security reinforces esignature legitimacy for technology industry in European Union, ensuring that sensitive information remains protected. Our platform also includes features like two-factor authentication to further safeguard user accounts and documents.

Related searches to esignature legitimacy for technology industry in european union

Join over 28 million airSlate SignNow users

Get more for esignature legitimacy for technology industry in european union

- Create a personal digital signature effortlessly

- Easily and securely manually sign PDF files

- Create an online signature effortlessly with airSlate ...

- Set up e-signature in PDF effortlessly with airSlate ...

- Easily generate a digital signature on a pdf with ...

- Effortlessly affix signature in document with airSlate ...

- Easily apply e-sign in PDF with airSlate SignNow

- Easily insert signature on PDF Mac with airSlate ...