187-274/Sections06

10/9/01

2:25 PM

Page 121

KNAUF FIBER GLASS, GMBH

121

IN RE KNAUF FIBER GLASS, GMBH

PSD Appeal Nos. 98–3 through 98–20

ORDER DENYING REVIEW IN PART

AND REMANDING IN PART

Decided February 4, 1999

Syllabus

On March 30, 1998, the Shasta County, California, Air Quality Management District

(“AQMD”) issued a federal Clean Air Act prevention of significant deterioration (“PSD”) permit to Knauf Fiber Glass, GmbH, authorizing the construction of a new fiberglass manufacturing plant to be located in the City of Shasta Lake, California. Petitions for review of the PSD

permit were filed by seventeen private citizens and citizens’ groups and by EPA Region IX.

The petitions for review cover the spectrum of issues relating to PSD review, as well

as several issues that fall outside of the Board’s jurisdiction over PSD permit decisions. This

decision discusses each of the issues raised in the petitions for review in reaching the holdings summarized below.

Held: Review is granted and AQMD’s permit decision is remanded as to the following issues:

•The BACT determination is being remanded to AQMD due to an incomplete BACT

analysis. Petitioners have raised legitimate questions about the particular control technology and emission limits for the proposed facility in light of alternative pollution control

equipment configurations at other fiberglass manufacturing facilities. The record does not

show that AQMD adequately considered the comments received on BACT. AQMD is to

prepare a supplemental BACT analysis that identifies multiple pollution control options

and provides infeasibility analyses as necessary. In preparing the supplemental BACT

analysis, AQMD need not require Knauf to pursue its competitors’ trade secrets, but it must

consider pollution control designs for other facilities that are a matter of public record.

(Section II.B.1.)

•The issue regarding environmental justice considerations is being remanded to

AQMD in order that an environmental justice determination prepared by EPA Region IX

may be added to the administrative record and made available for public comment.

(Section II.E.)

Review is denied as to all other issues raised in the petitions for review, including

the following:

•AQMD’s explanation for its use of PM10 monitoring data and meteorological data from

Redding, California, in lieu of on-site data, was adequate in light of the general comments

on data representativeness raised during the public comment period. (Section II.B.2.a.)

VOLUME 8

�187-274/Sections06

122

10/9/01

2:25 PM

Page 122

ENVIRONMENTAL ADMINISTRATIVE DECISIONS

•The air quality analysis for the proposed facility takes into account emissions from

other sources and adequately demonstrates compliance with the PM10 NAAQS and PSD

increments. (Section II.B.2.b.)

•Potential adverse impacts in nearby Class I and Class II areas have been adequately addressed in the administrative record. The air quality analysis demonstrates that there

will be no significant air quality impacts in Class I areas. A visibility analysis was performed

for three Class II National Recreation Areas and AQMD concluded that visibility impacts

from the proposed facility would be less than significant. (Section II.B.3.)

•Review of issues pertaining to hazardous air pollutants and/or unregulated pollutants is denied because control of such pollutants is not an explicit requirement of the federal PSD program and petitioners have not shown that their concerns otherwise fall within the purview of the federal PSD program. (Section II.C.1.)

•The use of a local landfill for disposal of solid waste from the proposed facility is not

subject to PSD review because: 1) waste disposal practices, including controls on the types

of waste that may be handled at a particular landfill, are not governed by the Clean Air Act;

and 2) petitioners have not established that potential emissions from a landfill site constitute

“secondary emissions” within the meaning of 40 C.F.R. § 52.21(b)(18). (Section II.C.2.)

•Requirements in the permit calling for PM 10 offsets and mitigation measures are not

requirements of the federal PSD program and petitioners have not shown that these issues

otherwise come within the purview of the federal PSD program. Therefore, the Board

denies review of these issues. (Section II.C.3.)

•The Board denies review of petitioners’ allegations regarding the impact of Shasta

County politics on the permit review process because the issues raised do not pertain to

requirements of the federal PSD program. (Section II.C.4.)

Before Environmental Appeals Judges Ronald L. McCallum

and Edward E. Reich. 1

Opinion of the Board by Judge McCallum:

On March 30, 1998, the Shasta County, California, Air Quality

Management District (“AQMD”) issued a federal prevention of significant

deterioration (“PSD”) permit, pursuant to Clean Air Act § 165, 42 U.S.C.

§ 7475, to Knauf Fiber Glass, GmbH (“Knauf”). The permit authorizes the

construction of a new fiberglass manufacturing plant to be located in the

City of Shasta Lake, California. AQMD is authorized to make PSD permit

1

Environmental Appeals Judge Kathie A. Stein did not participate in this decision.

Pursuant to an order issued February 4, 1999, the Board revised portions of its

November 30, 1998 Order Denying Review in Part and Remanding in Part in this case to

clarify certain language in the interest of avoiding possible misinterpretation. See Order on

Motions for Reconsideration (EAB, Feb. 4, 1999). This revised decision replaces and supersedes the November 30, 1998 decision. The November 30th decision, therefore, has no

precedential value in this or any other case.

VOLUME 8

�187-274/Sections06

10/9/01

2:25 PM

Page 123

KNAUF FIBER GLASS, GMBH

123

decisions for new and modified stationary sources of air pollution in

Shasta County pursuant to a 1985 delegation agreement with EPA Region

IX. Because AQMD acts as EPA’s delegate under the PSD program, permits are considered EPA-issued permits, and appeals of the permit decisions are heard by the Environmental Appeals Board pursuant to 40

C.F.R. § 124.19. See In re Maui Elec. Co., 8 E.A.D. 1, 2 n.1 (EAB 1998). In

this case, appeals of AQMD’s permit decision for Knauf were filed by seventeen private citizens and citizens’ groups and by EPA Region IX.

I. BACKGROUND

The City of Shasta Lake (“COSL”) is a recently incorporated city in

Shasta County, California, looking to create economic growth through

business development. Knauf would like to construct a new fiberglass

insulation manufacturing plant in COSL to serve the fiberglass market on

the west coast. COSL and the rest of Shasta County enjoy relatively clean

air. Shasta County has been designated an attainment or unclassifiable

area for national ambient air quality standards (“NAAQS”) pursuant to

section 107 of the Clean Air Act (“CAA”).2 42 U.S.C. § 7407; see also 40

C.F.R. § 81.305 (attainment status designations for California). COSL is in

close proximity to several national recreation areas, national wilderness

areas, and a national park.

Thus, the setting for this case involves virtually all of the factors enumerated in the congressional declaration of purpose for the prevention

of significant deterioration provisions of the CAA. CAA § 160, 42 U.S.C.

§ 7470. The PSD provisions outline a framework for managing economic

growth in areas of the country that meet NAAQS (or are designated as

“unclassifiable”). The provisions also call for special attention to air quality in certain national parks and national wilderness areas. CAA §§ 160(2),

165(d), 42 U.S.C. §§ 7470(2), 7475(d).

The statutory PSD provisions are carried out through a regulatory

process that requires preconstruction permits for new and modified major

stationary sources. See 40 C.F.R. § 52.21. PSD permitting requires that several important analyses be performed and taken into consideration in setting permit terms and conditions. One of the most critical elements of the

permit process is the selection of “best available control technology” or

2

NAAQS are maximum ambient air concentrations for the following six pollutants: sulfur dioxide, particulate matter (“PM”), carbon monoxide, ozone, nitrogen dioxide, and

lead. 40 C.F.R. §§ 50.4-50.12.

VOLUME 8

�187-274/Sections06

124

10/9/01

2:25 PM

Page 124

ENVIRONMENTAL ADMINISTRATIVE DECISIONS

“BACT” for pollutants subject to PSD review.3 An air quality analysis is

also required, the primary purpose of which is to determine whether a

proposed project would cause or contribute to exceedances of NAAQS

or PSD increments.4 Special review procedures apply to those projects

whose emissions may impact certain national parks, wilderness areas, or

other designated areas with “special national or regional natural, recreational scenic, or historic value.” CAA §§ 160(2), 165(d), 42 U.S.C.

§§ 7470(2), 7475(d). In addition to the technical requirements of PSD

review, the Clean Air Act emphasizes the importance of public participa tion and input into the decisionmaking process. See CAA §§ 160(5),

165(a)(2), 42 U.S.C. §§ 7470(5), 7475(a)(2). Each of these elements, and

several collateral concerns are at issue in this case and are discussed

more fully infra Sections II.B. and II.C.

A major industrial development project potentially involves numerous permitting and approval requirements by federal, state, and local

agencies. The PSD permit process is just one of these requirements. The

proposed Knauf project required a variety of permits and approvals in

addition to the PSD permit that is presently before us. In this case, PSD

review began after other review and approval procedures were underway. In particular, in November 1996, COSL initiated a review process

required by the California Environmental Quality Act (“CEQA”), Cal. Pub.

Res. Code § 21000 et seq. The principal product of the CEQA process was

the generation of an environmental impact report (“EIR”).5 In conjunction

with the CEQA process, COSL issued a conditional use permit, containing conditions on a wide variety of issues affecting construction and

operation of the proposed facility. CEQA, the EIR, and the conditional

use permit are distinct from PSD review and the PSD permit decision

issued by the AQMD pursuant to the Clean Air Act.

PSD review is triggered only for those pollutants that a new source has the potential

to emit at rates equal to or in excess of “significant” rates specified in 40 C.F.R.

§ 52.21(b)(23). See infra note 6 and accompanying text for a discussion of the significant

levels as applied to this case.

3

4

PSD increments are maximum allowable increases in pollutant concentrations permissible by regulation. See 40 C.F.R. § 52.21(c). The amount of the allowable increase

depends upon the classification of the area impacted by the emissions. See infra Section

II.B.3 for a discussion of area classifications.

5

Three versions of the EIR were prepared over the course of the CEQA process. They

are cited in this decision as follows: CH2MHill, City of Shasta Lake Industrial Project Draft

EIR (Feb. 1997) (“Draft EIR”); CH2MHill, Knauf Fiber Glass Manufacturing Facility Revised

Draft EIR (July 1997) (“Revised EIR”); CH2MHill, Final EIR Knauf Fiber Glass Manufacturing

Facility (Oct. 1997) (“Final EIR”).

VOLUME 8

�187-274/Sections06

10/9/01

2:25 PM

Page 125

KNAUF FIBER GLASS, GMBH

125

Knauf submitted a PSD permit application for the proposed fiberglass facility to the AQMD in March 1997. The facility is designed to

manufacture fiberglass insulation via a rotary spin manufacturing

process. The plans for the facility include production of 195 tons of insulation per day and 24-hour operations. The proposed facility is subject

to the PSD permitting process because it constitutes a “major stationary

source” under the PSD regulations. 40 C.F.R. § 52.21(b)(1)(i)(a). Federal

PSD review is required for emissions of particulate matter less than 10

micrometers in diameter (“PM10”) because the potential PM10 emissions

from the proposed Knauf facility exceed the “significant” level specified

in the PSD regulations.6 Emissions of other pollutants do not exceed the

regulatory significant levels and are not subject to PSD review.

On November 24, 1997, the AQMD issued a draft PSD permit for the

proposed Knauf facility and opened a 45–day public comment period. A

public hearing was held on January 7, 1998. AQMD issued its final permit decision on March 30, 1998. Federal Prevention of Significant

Deterioration (PSD) Authority to Construct (Mar. 30, 1998) (“Permit”). At

that time, AQMD also published two documents responding to comments

received during the public comment period and at the hearing. Response

to Comments, Written Comments Submitted During Public Comment

Period (“RTC”); Response to Comments, Public Hearing 1/7/98 (“RTPH”).

The Board received eighteen petitions for review regarding AQMD’s

permit decision for Knauf. Seventeen of the petitions for review were

filed by local citizens or citizens’ groups.7 One petition for review was

filed by EPA Region IX, the EPA regional office with responsibility for

activities in California. Petition No. 98–19.

A large number of the citizen petitions express displeasure over the

decision to site the Knauf facility in COSL, or the Shasta County region

generally. Several petitioners requested that the permit be denied. In

addition, each petition raised one or more issues challenging conditions

of the permit and/or elements of the permitting process.

6

PSD review is triggered for PM10 if a source has the potential to emit 15 tons per year

or more of PM10 emissions. 40 C.F.R. § 52.21(b)(23)(i). The proposed Knauf facility is

expected to emit PM 10 at a rate of 191 tons per year.

The petitioners (and corresponding appeal numbers) are: Bryan Hill, Mother Lode

Chapter, Sierra Club (98–3), Laurie Holstein, Citizens for Cleaner Air (98–4), Ivan Hall

(98–5), Mary Scott, Citizens for Cleaner Air (98–6), Citizens for Responsible Growth &

Valley Advocates, Inc. (98–7), Colleen Leavitt (98–8), Barbara Frisbie (98–9), Robert

Swendiman (98–10), Fulton M. Doty (98-11), Linda Andrews (98–12), Arnold Erickson

(98–13), Laurie O’Connell (98–14), Betty Doty (98–15), Warren L. Teel (98–16), John Hickey

(98–17), Patricia Cogburn (98–18), and Deborah Lynn Fisher (98–20). The petitions for

review are cited throughout this decision as “Petition No. __.”

7

VOLUME 8

�187-274/Sections06

126

10/9/01

2:25 PM

Page 126

ENVIRONMENTAL ADMINISTRATIVE DECISIONS

In accordance with the Board’s practice in permit appeals, the Board

requested that AQMD prepare responses to the petitions for review.8 In

addition, acting on motions, the Board granted Knauf an opportunity to

file a response to the petitions and accepted an amicus brief from COSL.

Order on Pending Motions (June 23, 1998). The Board also provided petitioners an opportunity to file replies to the materials submitted by Knauf,

AQMD, and COSL. 9 Id. Region IX’s reply memorandum presented a proposed settlement of the issue presented in its petition for review.10 In

response to a motion, the Board granted petitioners who had raised the

same issue as Region IX an opportunity to submit a response to the settlement proposed in Region IX’s memorandum. Order Granting

Opportunity to Respond to Reply Memorandum Submitted by EPA

Region IX (Aug. 6, 1998).11

II. DISCUSSION

A. Standard of Review

The role of the Environmental Appeals Board in the PSD permitting

process is to consider issues raised in petitions for review that pertain to

the PSD program and that meet the threshold procedural requirements of

the permit appeal regulations. See 40 C.F.R. § 124.19. A petitioner must

have both standing to appeal and must be seeking review of issues that

have been properly preserved for review. If these threshold requirements

are satisfied, the Board will consider whether to “grant review” of any of

the issues included in a petition for review.

The permit appeal regulations provide for review only if a permit

decision was based on either a clearly erroneous finding of fact or

8

AQMD’s responses are cited in this decision as “AQMD [Petition #] Resp.”

The Board considered all petitioner replies that related to issues raised in the petitions for review. The Board did not consider new issues raised in the reply briefs. New

issues raised for the first time at the reply stage of these proceedings are equivalent to late

filed appeals and must be denied on the basis of timeliness. See In re Beckman Prod.

Servs., 5 E.A.D. 10, 15 (EAB 1994) (denying review of a petition that was filed after the thirty-day period specified in 40 C.F.R. § 124.19(a)). The petitioner replies are cited as “Reply

[Petition #].”

9

10

The details of the proposed settlement are discussed infra notes 35–36 and accompanying text.

The Board’s August 6, 1998 order provided the final opportunity for submitting

materials to be considered by the Board in reaching a decision on whether or not to grant

review. Correspondence received after the deadline set forth in the order was not considered by the Board.

11

VOLUME 8

�187-274/Sections06

10/9/01

2:25 PM

Page 127

KNAUF FIBER GLASS, GMBH

127

conclusion of law, or if the decision involves an important matter of policy or exercise of discretion that warrants review. 40 C.F.R. § 124.19(a). In

applying this standard for granting review, the Board has been guided by

the following language in the preamble to section 124.19: the “power of

review should be only sparingly exercised” and “most permit conditions

should be finally determined at the [permitting authority] level.” 45 Fed.

Reg. 33,290, 33,412 (May 19, 1980); accord In re Maui Elec. Co., 8 E.A.D.

1, 7 (EAB 1998); In re Kawaihae Cogeneration Project, 7 E.A.D. 107, 114

(EAB 1997).

One way that the Board implements the standard of review in

40 C.F.R. § 124.19 is to require petitioners to state their objections to a

permit and to explain why the permitting authority’s response to those

objections (for example, in a response to comments document) is clearly erroneous or otherwise warrants review. Kawaihae, 7 E.A.D. at 114;

In re Puerto Rico Elec. Power Auth., 6 E.A.D. 253, 255 (EAB 1995). It is

not enough to simply reiterate comments made to the permitting authority. In re LCP Chems., 4 E.A.D. 661, 664 (EAB 1993).

Despite the strict standard of review and the Board’s expectations in

petitions for review, the Board tries to construe petitions filed by persons

unrepresented by legal counsel broadly. See In re Envotech, L.P., 6 E.A.D.

260, 268 (EAB 1996); In re Beckman Prod. Servs., 5 E.A.D. 10, 19 (EAB

1994). The Board does not expect such petitions to contain sophisticated

legal arguments or to employ precise technical or legal terms. However,

the Board does expect such petitions to provide sufficient specificity such

that the Board can ascertain what issue is being raised. Puerto Rico,

6 E.A.D. at 255. The Board also expects the petition to articulate some

supportable reason as to why the permitting authority erred or why

review is otherwise warranted. Beckman, 5 E.A.D. at 19.

Finally, it is possible that some issues will still not warrant a grant of

review, even if the issues have been properly preserved for review and

the petitions contain sufficient specificity. Issues that are not covered by

the PSD program fall into this category. The PSD review process is not

an open forum for consideration of every environmental aspect of a proposed project, or even every issue that bears on air quality. In fact, certain issues are expressly excluded from the PSD permitting process. The

Board will deny review of issues that are not governed by the PSD regulations because it lacks jurisdiction over them.

The majority of issues raised in the petitions for review can be loosely categorized into three groups. The first group includes issues that are

reviewable under the PSD program and that were properly preserved for

VOLUME 8

�187-274/Sections06

128

10/9/01

2:25 PM

Page 128

ENVIRONMENTAL ADMINISTRATIVE DECISIONS

review in this case. We refer to these issues as “PSD issues.” The PSD

issues include, among others: questions about AQMD’s BACT determination, adequacy of the air quality analysis, and issues relating to impacts

in Class I and Class II areas. The second group of issues are items that

fall outside of the Board’s jurisdiction over PSD permit decisions because,

as presented in the petitions, they lack a nexus to the PSD program.

These issues are denominated “non-PSD” issues for convenient reference.

Some of the non-PSD issues are: control of hazardous air pollutants and

“unregulated” pollutants, disposal of fiberglass waste at local landfills,

plans for PM10 mitigation, adequacy of the EIR prepared pursuant to

CEQA, and the role of Shasta County politics in the permitting process.

In the third category are a few issues that must be denied because the

threshold requirements for review under 40 C.F.R. § 124.19 were not satisfied. Last, we address the issue of environmental justice, which does not

readily fit into one of the three categories mentioned above.

B. PSD Issues

1. BACT Determination

The Clean Air Act and the PSD regulations require that major new

stationary sources such as the proposed Knauf facility employ the “best

available control technology” to limit emissions of certain pollutants. CAA

§ 165(a)(4), 42 U.S.C. § 7475(a)(4); 40 C.F.R. § 52.21(j)(2). BACT is defined

in the PSD regulations as follows:

Best available control technology means an emissions

limitation * * * based on the maximum degree of reduction for each pollutant subject to regulation under [the]

Act which would be emitted from any proposed major

stationary source * * * which the Administrator, on a caseby-case basis, taking into account energy, environmental,

and economic impacts and other costs, determines is

achievable for such source * * * through application of

production processes or available methods, systems, and

techniques * * * for control of such pollutant.

40 C.F.R. § 52.21(b)(12). As the definition indicates, there are several considerations that form a part of the BACT determination. The combined

result of these considerations is the selection of an emission limitation12

and control technology that are specific to a particular facility. In reaching

12

The term “emission limitation” is defined broadly in the CAA:

Continued

VOLUME 8

�187-274/Sections06

10/9/01

2:25 PM

Page 129

KNAUF FIBER GLASS, GMBH

129

this facility-specific result, the emission limitations achieved by other facilities

and corresponding control technologies used at other facilities are an important source of information in determining what constitutes best available.

In an effort to lend some consistency and a framework to BACT

determinations being made by permit issuing authorities such as AQMD,

EPA has issued a guidance document that is widely used in PSD reviews.

U.S. EPA, New Source Review Workshop Manual (Draft Oct. 1990) (“NSR

Manual”).13 A section of the NSR Manual addresses the BACT determination process. The NSR Manual’s approach is structured to take into

account all of the elements in the regulatory definition of BACT. The

essence of the BACT determination process as described in the NSR

Manual is to look for the most stringent emissions limits achieved in practice at similar facilities and to evaluate the technical feasibility of implementing such limits and/or control technologies for the project under

consideration.

The BACT process leads to the selection of specific emission limitations

through an analysis of pollution control options for the proposed project. A

control option may be an “add-on” air pollution control technology that

removes pollutants from a facility’s emissions stream, or an “inherently

lower-polluting process/practice” that prevents emissions from being generated in the first instance. NSR Manual at B.10, B.13. The petitioners’ challenges to the BACT determination in this case raise issues relating to both

add-on control technology and inherently lower-polluting processes.

The BACT selection process, as set forth in the NSR Manual, was

most recently outlined by the Board in Maui Elec., 8 E.A.D. at 6.14 The first

step in the BACT selection process involves identifying and listing all

‘[E]mission limitation’ * * * mean[s] a requirement * * * which limits the quantity,

rate, or concentration of emissions of air pollutants on a continuous basis, including any requirement relating to the operation or maintenance of a source to

assure continuous emission reduction, and any design, equipment, work practice, or operational standard promulgated under [the CAA].

CAA § 302(k), 42 U.S.C. § 7602(k). An emission limitation is ordinarily expressed as a

numerical limit on the rate of emissions.

13

Although the NSR Manual is not a binding rule, we have looked to it as a statement

of the Agency’s thinking on certain PSD issues. See, e.g., In re Maui Elec. Co., 8 E.A.D. 1,

5 (EAB 1998); In re Kawaihae Cogeneration Project, 7 E.A.D. 107, 112 (EAB 1997).

14

The BACT process described in the NSR Manual is not a mandatory methodology, but

permitting authorities normally use it. See Kawaihae, 7 E.A.D. at 113. EPA recommends use

of the NSR Manual methodology because it provides for application of all of the

BACT regulatory criteria through a step-wise framework, that if followed, should yield a

Continued

VOLUME 8

�187-274/Sections06

130

10/9/01

2:25 PM

Page 130

ENVIRONMENTAL ADMINISTRATIVE DECISIONS

“available” control options. NSR Manual at B.5. The term available is used

in its broadest sense under the first step and refers to control options with

a “practical potential for application to the emissions unit” under evaluation. Id. (emphasis added). The goal of this step is to develop a compr ehensive list of control options. In compiling the list of available control

options, a variety of information sources may be reviewed, including

information on pollution control and emission limitations for other industrial facilities.

The second step of the BACT analysis is to consider the technical

feasibility of the control options identified in step one. During the course

of this step, technically infeasible control options are eliminated from

consideration. Id. at B.7. The purpose of this step of the BACT analysis

is to determine which of the options identified in step one can be practically deployed on the proposed project.

The technical feasibility step focuses on whether a control option is

“available” and “applicable.” Id. at B.17. Availability in this context is

somewhat different from the concept of “available” in step one. For purposes of technical feasibility, available refers to commercial availability.

Id. A technology is considered applicable if it can be “reasonably

installed and operated on the source type under consideration.” Id.

Applicability focuses on how a particular control option has been used

in the past and how those uses compare to the project under consideration. A control option is presumed applicable if it has been used on the

same or similar type of source as the proposed project. Id. at B.18. Issues

of applicability may be particularly critical in analyzing inherently lowerpolluting processes and other types of process controls.

If a permit applicant asserts that a particular control option is technically infeasible, the applicant should provide factual support for that

assertion. Such factual support may address commercial unavailability or

difficulties associated with application of a particular control to the permit applicant’s project. Id. at B.19. A control option is not considered

infeasible simply based upon the cost of applying that option to the proposed project. Economic feasibility is evaluated in a subsequent step of

the BACT process. Id. at B.20.

defensible BACT determination. We would not reject a BACT determination simply because

the permitting authority deviated from the NSR Manual, but we would scrutinize such a

determination carefully to ensure that all regulatory criteria were considered and applied

appropriately.

VOLUME 8

�187-274/Sections06

10/9/01

2:25 PM

Page 131

KNAUF FIBER GLASS, GMBH

131

The technical feasibility analysis requires application of technical

judgment on the part of the permitting authority. The permitting authority must assess the materials presented by the permit applicant and ultimately must decide which options are technically feasible. Id. at B.22.

Once technical feasibility has been considered and any infeasible

options are eliminated, the third step of the BACT analysis is to list the

remaining options in order of stringency, with the most stringent option

listed first. In step four, collateral energy, environmental, and economic

impacts are considered, beginning with the “top” control option.15

Consideration of these collateral impacts “operates primarily as a safety

valve whenever unusual circumstances specific to the facility make it

appropriate to use less than the most effective technology.” In re

Columbia Gulf Transmission Co., 2 E.A.D. 824, 827 (Adm’r 1989).

Collateral impacts are generally reviewed in determining which of several available control technologies produces less adverse collateral effects,

and whether such effects justify the use of a less stringent control technology.16 In re Old Dominion Elec. Coop., 3 E.A.D. 779, 792 (Adm’r 1992).

In short, under the NSR Manual methodology, consideration of collateral

impacts is used to either confirm the top BACT option as appropriate or

to demonstrate that it is inappropriate. Maui Elec., 8 E.A.D. at 6. If the top

option is eliminated based on one of these considerations, the next most

stringent option is considered. Ultimately, “[t]he most effective control

alternative not eliminated * * * is selected as BACT.” NSR Manual at B.53.

The BACT analysis is one of the most critical elements of the PSD

permitting process. As such, it should be well documented in the administrative record. A permitting authority’s decision to eliminate potential

control options as a matter of technical infeasibility, or due to collateral

impacts, must be adequately explained and justified. See In re Masonite

Corp., 5 E.A.D. 551, 566 (EAB 1994) (remanding PSD permit decision in

part because BACT determination for one emission source was based on

an incomplete cost-effectiveness analysis); In re Pennsauken County,

N.J., Resource Recovery Facility, 2 E.A.D. 667, 672 (Adm’r 1988) (remanding PSD permit decision because “[t]he applicant’s BACT analysis * * *

does not contain the level of detail and analysis necessary to satisfy the

applicant’s burden” of showing that a particular control technology is

15

Collateral energy and economic impacts need not be analyzed if the permit applicant accepts the top control option. NSR Manual at B.26. Consideration of collateral environmental impacts is nonetheless expected at this step. Id.

16

In some cases—for example, when BACT is analyzed outside the structured

approach of the NSR Manual—consideration of collateral impacts, particularly collateral

environmental impacts, may require rejection of a less stringent control option in favor of

a more stringent option. See In re North County Resource Recovery Assocs., 2 E.A.D. 229,

230-31 (Adm’r 1986).

VOLUME 8

�187-274/Sections06

132

10/9/01

2:25 PM

Page 132

ENVIRONMENTAL ADMINISTRATIVE DECISIONS

technically or economically unachievable); Columbia Gulf, 2 E.A.D. at

830 (permit applicant and permit issuer must provide substantiation

when rejecting the most effective technology). In the context of a permit

appeal, the Board will look at the BACT determination, as documented

in the record, to determine whether it reflects “considered judgment” on

the part of the permitting authority. See In re Ash Grove Cement Co.,

7 E.A.D. 387, 417–19 (EAB 1997) (remanding RCRA permit because permitting authority’s rationale for certain permit limits was not clear and

therefore did not reflect considered judgment); In re Austin Powder Co.,

6 E.A.D. 713, 720 (EAB 1997) (remand due to lack of clarity in permitting

authority’s explanation).

The BACT determination at issue in this case involves control of PM10

emissions from the forming section of the proposed Knauf facility.

Virtually all of the PM10 emissions from the plant are generated by the

forming process. AQMD’s PM10 BACT determination for Knauf’s forming

section is memorialized in a permit condition requiring installation of

seven venturi17 scrubbers followed by a wet electrostatic precipitator

(“WEP”).18 Permit ¶ 48.a. These items are add-on pollution control technologies that remove particulate matter from the exhaust gas stream

before release through the main stack. The PM10 emission limit (i.e., maximum allowable emission rate) from the main stack is 43.6 lbs/hr or 5.37

lbs/ton of glass pulled.19 Permit ¶ 53. Although these limits are for PM10,

the values in the permit are expressed as total suspended particulate

(“TSP”).20 The permit also imposes a production limit of 195 tons of glass

per day. 21 Permit ¶ 36.

17

The permit specifically calls for venturi scrubbers, although other documents in the

administrative record refer to the scrubbers simply as “wet” scrubbers. We will follow the

terminology as used in the particular record document being cited in our discussion.

18

Six of the venturi scrubbers are designated for the bonded wool forming line; one

scrubber is to be used on the unbonded wool forming line. All seven scrubbers will vent

to the WEP. Permit ¶ 48.a. The venturi scrubbers remove suspended particulate matter and

provide “pretreatment” of the exhaust gas prior to the WEP. Id. ¶ 49. Operating parameters for the pollution control devices are specified in the permit and must be measured

every 15 minutes. Id. ¶ 51.

19

Emission limits for the fiberglass industry are commonly expressed in units of pounds

per ton of glass pulled. See 49 Fed. Reg. 4590, 4596 (Feb. 7, 1984). This type of limit pegs

the allowable emissions to the plant’s production rate. We abbreviate these units as “lbs/ton.”

20

AQMD does not explain why PM10 limits are expressed in terms of TSP, but it

appears that the test method designated in the permit for measuring PM10 emissions yields

results as TSP rather than PM10. See Permit ¶ 53 (designating EPA test method 5E for determining PM10 emissions); 40 C.F.R. part 60 app. A, Method 5E.

21

Both the per hour emission limit and per ton of glass pulled limit produce nearly

identical PM 10 emission rates, differing by only one pound per day. The hourly emission

limit, multiplied by 24 hours, yields a daily emission rate of 1,046 lbs/day. The daily production limit multiplied by the per ton of glass pulled emission limit for PM10 yields a daily

emission rate for PM 10 of 1,047 lbs/day.

VOLUME 8

�187-274/Sections06

10/9/01

2:25 PM

Page 133

KNAUF FIBER GLASS, GMBH

133

The challenges to these permit terms raised by some of the petitioners require a further examination of AQMD’s BACT determination as documented in the administrative record.22 The documentation of the BACT

analysis and decision is principally in Knauf’s permit application, AQMD’s

permit evaluation, the RTC, and the RTPH.

Table 1 is our summary of information in the administrative record

pertaining to control technologies and emission limits for PM10 on fiberglass forming lines. Each row in the table corresponds to a specific fiberglass manufacturing facility mentioned in the administrative record. For

each facility, we have listed the control technology used to limit PM10

emissions from the forming line, the PM10 emission limit, and the source

of information on the facility from the Knauf administrative record. As far

as we can discern, this is the primary information that underlies the PM10

BACT determination for the proposed Knauf plant. The background of

each of the entries in the table is explained in the subsequent discussion.

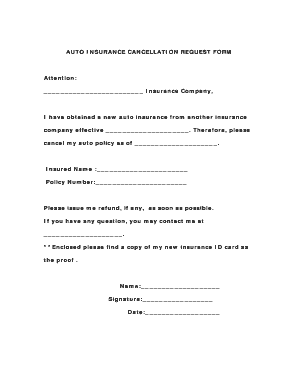

TABLE 1

Administrative Record Information on PM10 Permit Limits

for Fiberglass Forming Lines

Company/

Location

Control

Technology

PM10 Emission

Limit

Source in the

Admin. Record

Knauf/

Lanett,AL

wet scrubber

with thermal oxidizer

7.71 lbs/ton

Permit

Application

B

CertainTeed/

Chowchilla,CA

wet scrubber(s)

plus three WEPs

~1.0 lb/ton

AQMD

Evaluation/

Public Comments

C

Owens Corning/

Santa Clara,CA

Unknown23

Unknown

AQMD

Evaluation

D

Schuller/

Willows,CA

Unknown

Unknown

AQMD

Evaluation

E

CertainTeed/

Kansas City, KS

three WEPs

3.63 lbs/ton

(as TSP)

2.02 lbs/ton (as PM 10)

Public

Comments

F

Knauf/

COSL,CA

(proposed)

7 venturi

scrubbers plus

one WEP

5.37 lbs/ton

(as TSP)

Permit

A

22

Our assessment of this issue is largely based upon the administrative record documents provided for our review. In addition, we reviewed the administrative record index

for additional materials that appear to relate to AQMD’s BACT determination.

23

We found no information on PM10 permit limits for the forming sections of the

Owens Corning or Schuller plants in the excerpts of the administrative record that were

provided to us for review.

VOLUME 8

�187-274/Sections06

134

10/9/01

2:25 PM

Page 134

ENVIRONMENTAL ADMINISTRATIVE DECISIONS

Knauf’s permit application contains the initial BACT analysis for the

proposed facility. PSD Permit Application Revision 2 at 26–29 (July 17,

1997) (“Permit App.”). Knauf’s BACT analysis indicates that EPA’s

RACT/BACT/LAER Clearinghouse24 (“RBLC”) was searched for all fiberglass manufacturing entries since 1985. Permit App. at 28. Without discussing the results of that search, the application concludes that only one

facility in the RBLC was similar to the proposed facility for Shasta Lake.

“The similar facility is the Knauf GmbH Lanett, Alabama facility.” Id. The

PM10 control technology used at the Lanett facility is a wet scrubber with

thermal oxidizer and a corresponding emission limit of 7.71 lbs/ton. Id.

See supra Table 1, Row A. The permit application for the proposed facility in COSL also discusses use of an electrostatic precipitator in order to

comply with one of AQMD’s local rules. Permit App. at 29. The permit

application concludes that “seven (7) wet scrubbers * * * and a wet ESP”

constitute BACT and “no further evaluation of particulate control technologies is necessary.” Id.

Although the permit application describes the conclusion of Knauf’s

BACT analysis, it lacks a clearly ascertainable basis for the conclusion.

The overall discussion is cursory and does not explain how the decision

satisfies the regulatory criteria. The basis for the conclusion might have

been ascertainable had Knauf documented the preliminary steps of a

BACT determination as outlined in the NSR Manual and described

above.25 As it stands, the permit application does not include a listing of

all possible control options, a discussion of emission control technologies

and limits for fiberglass manufacturing facilities other than the Knauf

plant in Alabama, or a technical feasibility analysis. Without this type of

information, it is impossible to know if Knauf really adopted the most

stringent option available as BACT.

AQMD’s Authority to Construct/PSD Permit Evaluation (Nov. 21,

1997) (“AQMD Evaluation”) provides slightly more detail on selection of

BACT than the permit application. AQMD states that a survey of other

24

RACT/BACT/LAER stands for Reasonably Available Control Technology/Best

Available Control Technology/Lowest Achievable Emission Rate. Each of these acronyms

refers to technological standards established by different sections of the CAA. BACT is the

standard from the PSD provisions of the CAA. See CAA § 165(a)(4), 42 U.S.C. § 7475(a)(4).

The RBLC contains information on emission controls and emission limits for industrial facilities across the country. The RBLC is organized by source category, thereby making it relatively easy to access emission control information for a particular industrial enterprise.

25

As noted supra note 14, a strict application of the methodology described in the NSR

Manual is not mandatory, but we expect an analysis that is as sufficiently detailed as the

model in the NSR Manual.

VOLUME 8

�187-274/Sections06

10/9/01

2:25 PM

Page 135

KNAUF FIBER GLASS, GMBH

135

fiberglass facilities with similar emissions units in California was conducted. AQMD Evaluation at 9. The document lists three California facilities

that were reviewed in addition to Knauf’s Alabama facility. The owners

and locations of these other facilities are: 1) CertainTeed, in Chowchilla,

CA; 2) Owens Corning, in Santa Clara, CA; and 3) Schuller/Johns

Manville 26 in Willows, CA. The permit evaluation states that the

CertainTeed Chowchilla plant uses a wet scrubber followed by a WEP to

control PM10 emissions. Id. at 11. See supra Table 1, Row B. “No other facility appeared to have emission control equipment with this level of control.” AQMD Evaluation at 11. Presumably, this statement means that the

Chowchilla facility had the best emissions control equipment of the facilities reviewed. However, there is no discussion of what controls or emission limitations are in place at the Owens Corning or Schuller/Johns

Manville facilities in order to confirm that conclusion. See supra Table 1,

Rows C&D. AQMD ultimately concurs in Knauf’s conclusion that wet

scrubbers and a WEP is BACT for PM10. AQMD Evaluation at 11.

Despite the minimal discussion in the permit application and

AQMD’s evaluation regarding other facilities, the administrative record

index for this project includes several items regarding the above mentioned California fiberglass facilities. 27 We do not know what these items

consist of and the record does not appear to contain any analysis of the

contents. It may be that some or all of these items would support the

BACT determination here, however, no argument has been raised along

these lines.

During the public comment period on the draft permit, several commenters questioned why the PM10 BACT determination for Knauf resulted in less stringent PM10 limits than the limits at the CertainTeed

Chowchilla facility. Commenters pointed out that the Chowchilla facility

has a PM 10 emission limit of approximately 1.0 lb/ton. See RTC at 14, 20.

In addition, EPA Region IX identified a CertainTeed facility in Kansas City,

Kansas, (see supra Table 1, Row E) with lower PM10 limits than those proposed for Knauf. See RTC at 20.

In response, AQMD reiterated that the control technology selected

for the Knauf plant (venturi scrubbers and a WEP) constitute the most

26

The facility in Willows is referred to as both Schuller and Johns Manville in the

administrative record.

Items pertaining to the CertainTeed Chowchilla facility appear to be included in the

administrative record index as follows: Vol. I.A. at 278-306, Vol. I.B. at 801. References to

the Owens Corning facility include: Vol I.A. at 307, Vol II.E. Schuller/Johns Manville materials are listed at: Vol. I.A. at 800, Vol. II.D.

27

VOLUME 8

�187-274/Sections06

136

10/9/01

2:25 PM

Page 136

ENVIRONMENTAL ADMINISTRATIVE DECISIONS

effective emission control devices demonstrated in practice for control of

PM10 from fiberglass forming lines. RTC at 15, 21. AQMD also attempted

to explain the reason for the discrepancy between emission limits at the

CertainTeed facilities and the proposed Knauf plant. “[T]he emission limits established for PM 10 in other issued permits for fiberglass manufacturing facilities vary considerably since each process is different and uses

patented process design techniques that are not available to others in the

industry.” RTC at 21. The CertainTeed facilities use unique forming

process technology that is proprietary and not available to other manufacturers. Id. CertainTeed’s unique process in Kansas City was identified

only as a “European” process, the details of which are not publicly available. Id. Apparently, AQMD focused on the different process technologies used by Knauf and CertainTeed because the process “influences profoundly” the amount of PM10 emissions generated before control equipment is applied. Knauf Resp. at 22. Hence, even the use of the same addon controls may not yield the same emission rate when deployed on different processes.

AQMD’s response to comments also asserted that a commenter’s

request that Knauf achieve the same emission rates as the CertainTeed

plants would amount to a redefinition of the source. RTC at 15, 21.

AQMD presumed that Knauf would have to adopt CertainTeed’s process

technology in order to achieve emission rates comparable to

CertainTeed’s plants.

“Redefining the source” is a term of art described in the NSR Manual.

The Manual states that it is legitimate to look at inherently lower-polluting processes in the BACT analysis, but EPA has not generally required a

source to change (i.e., redefine) its basic design. NSR Manual at B.13. The

classic example of redefining a source involves a proposal to construct a

coal-fired power plant or boiler. See In re SEI Birchwood, Inc., 5 E.A.D.

25, 29 n.8 (EAB 1994). Such a proposal need not consider the alternative

of a natural gas-fired unit as part of the BACT determination, even though

a natural gas unit would be inherently less polluting than the coal-fired

unit. Id.; In re Hawaiian Commercial & Sugar Co., 4 E.A.D. 95, 99–100

(EAB 1992); In re Old Dominion Elec. Coop., 3 E.A.D. 779, 793 (Adm’r

1992). Substitution of a gas-fired power plant for a planned coal-fired

plant would amount to redefining the source. Although it is not EPA’s

policy to require a source to employ a different design, redefinition of the

source is not always prohibited. This is a matter for the permitting authority’s discretion. The permitting authority may require consideration of

alternative production processes in the BACT analysis when appropriate.

See NSR Manual at B.13–B.14; Old Dominion, 3 E.A.D. at 793 (permit

issuer has discretion “to consider clean fuels other than those proposed

by the permit applicant.”).

VOLUME 8

�187-274/Sections06

10/9/01

2:25 PM

Page 137

KNAUF FIBER GLASS, GMBH

137

The petitions for review that raise the BACT issue generally reiterate

the comments submitted on the draft permit.28 Several of the petitioners

echo arguments made by Region IX, namely, that the PM10 emission limit

for Knauf should be lowered in light of the more stringent limits in place

at the CertainTeed facilities, or that Knauf should be required to demonstrate why such lower limits are infeasible. Petition No. 98–19 at 4; see

also Petition Nos. 98–4, 98–5, 98–17 & 98–18. Other petitioners point out

differences in the control technology configuration between

CertainTeed’s Kansas City plant and Knauf’s proposal. The permit for the

Kansas City facility requires use of three WEPs in its forming section,

whereas the Knauf permit calls for only one WEP. Petition Nos. 98–3,

98–5 & 98–6. One petitioner, reacting to AQMD’s discussion of redefining the source, asserts that Knauf should be required to license or purchase the lower-polluting process technology used by CertainTeed.

Petition No. 98–16.

AQMD and Knauf present several arguments in defense of both the

selected control option (i.e., venturi scrubbers and a WEP) and the emission limits (i.e., 5.37 lbs/ton and glass production limit of 195 lbs/day).

With regard to the emission limits, AQMD and Knauf emphasize the differences between CertainTeed’s facilities and the proposed Knauf facility. First, AQMD argues that the CertainTeed facilities are not similar to the

Knauf facility. AQMD 98–19 Resp. at 1. AQMD notes that the CertainTeed

facilities use proprietary process technologies including: molten glass

chemistry, glass fiberization techniques, binder chemistry, binder application techniques, mat formation methods, and product mix. Id.

According to Knauf, these unique and proprietary processes affect the

amount of PM10 generated during manufacturing before application of

any pollution control technology. Knauf Resp. at 22. Thus, Knauf attributes the different emission rates among various facilities to the underlying process technologies.

AQMD and Knauf also point out that even the emission limits for

the two CertainTeed facilities vary widely. The Chowchilla facility has a

PM10 limit of approximately 1.0 lb/ton. In contrast, the PM10 limits for the

Kansas City facility are 2.02 lbs/ton for PM10 and 3.63 lbs/ton for PM (as

TSP). Moreover, the Kansas City permit, with the higher emission limits,

is the more recent permit decision.29 AQMD 98–19 Resp. at 4; Knauf

Resp. at 25.

28

Petition Nos. 98–3 through 98–6, and 98–16 through 98–19 challenge the BACT

determination for PM 10.

29

The PSD permit for CertainTeed’s facility in Kansas City, KS was issued on May 23,

1997. The permit for the Chowchilla, CA facility dates back to November 1983, with modifications in 1986, 1992, and 1995. Petition No. 98-19 atts. 5 & 6.

VOLUME 8

�187-274/Sections06

138

10/9/01

2:25 PM

Page 138

ENVIRONMENTAL ADMINISTRATIVE DECISIONS

AQMD adds that the PM10 emission limit in this case is based on the

WEP vendor’s performance guarantee, which in turn depends on the

nature of the exhaust stream entering the WEP. AQMD 98–19 Resp. at 2.

AQMD claims that it cannot justify an emission limit lower than what the

pollution control technology vendor can supply. Id. at 2, 5. Proposals

from three different WEP vendors attached to AQMD’s response each

indicate approximately the same guaranteed emission limit.30

Both Knauf and AQMD repeat the suggestion that Region IX is seeking to require Knauf to redefine its source. AQMD 98–19 Resp. at 6; Knauf

Resp. at 30–31. AQMD and Knauf believe that the only way to achieve the

CertainTeed emission limits would be to apply CertainTeed’s process technology, and such a requirement would amount to redefinition of the

source, even if Knauf could obtain CertainTeed’s proprietary technology.

In response to Region IX’s suggestion that Knauf should be required

to show that stricter emission limits are technically infeasible, AQMD

states that such a showing cannot be performed because the manufacturing techniques and process technologies used by CertainTeed are

unknown. AQMD 98–19 Resp. at 6. AQMD also represents that it previously requested Knauf to “respond to the possibility of achieving the lowest achievable emission rate of approximately 1.0 lb PM10 per ton of glass

pulled.” Id. at 3. Knauf responded that in light of the proprietary processes at CertainTeed, the specific characteristics of Knauf’s own process, and

the performance guarantees from Knauf’s WEP vendors, the emission rate

would have to be 5.37 lbs/ton. Id.

With regard to the differences in control technology configuration at

CertainTeed’s Kansas City facility and the proposed Knauf plant, both

AQMD and Knauf reject the concept that CertainTeed’s lower emission

limits are due to the fact that CertainTeed has three WEPs on its forming

section as compared to one WEP for Knauf. AQMD states that

CertainTeed splits the air flow from its forming section and each of the

three WEPs treats a portion of that flow. “[A]ll of the WEPs are not operating to reduce emissions from one source.” AQMD 98–5 Resp. at 3.

Knauf plans to use a single, larger WEP that receives combined air flow.

Id. Knauf claims that the WEP design for its plant is the equivalent of two

parallel WEPs. Knauf Resp. at 35. In addition, the proposed Knauf facility will use scrubbers. Id. Again, AQMD and Knauf attribute the difference

in emission limits to the differences in the underlying processes rather

than the WEP configuration. AQMD 98–3 Resp. at 2; Knauf Resp. at 35.

Emission limit guarantees were expressed as WEP outlet loadings of 0.015

grains/scfd.

30

VOLUME 8

�187-274/Sections06

10/9/01

2:25 PM

Page 139

KNAUF FIBER GLASS, GMBH

139

In sum, AQMD and Knauf’s responses to the BACT challenges focus

on the inherent differences between the CertainTeed and Knauf manufacturing processes. The differences are allegedly so great, that despite

the fact that both companies are operating (or planning to operate) rotary

spin manufacturing plants with substantially the same pollution control

technology (WEPs or scrubbers plus a WEP), the emission limits for one

company cannot be considered applicable to the other.

EPA’s history of regulating the fiberglass industry lends some support

to AQMD and Knauf’s position. For example, when EPA was proposing

New Source Performance Standards (“NSPS”) for the fiberglass manufacturing industry in the mid-1980s, the Agency addressed the fact that certain plants used process modifications in lieu of or in addition to add-on

pollution control technologies:

[B]ecause of the differences in the process design and

operation employed among firms, and in the products

produced by different firms (and in some cases by different plants within the same firm), the Agency does not

have a basis upon which to conclude that a process modification which has been demonstrated at one plant will

necessarily be applicable to another plant. Therefore, the

Administrator has determined that process modifications

are not an appropriate candidate [best demonstrated

technology] for this industry.

49 Fed. Reg. 4590, 4593 (Feb. 7, 1984). In the preamble to the final NSPS,

the Agency furthered explained why process modifications did not form

the basis for the NSPS standard, even though such modifications could

result in lower emissions:

The Agency agrees that use of [process] modifications,

alone or in combination with add-on control devices, can

achieve lower emissions than those allowed by the standard. However, process modifications are considered

confidential by the companies that comprise the fiberglass industry and are not generally available to the entire

industry.

50 Fed. Reg. 7694, 7696 (Feb. 25, 1985). In the course of the NSPS rulemaking, EPA rejected more stringent PM emission limits because such

limits would be based on confidential process modifications. See 49 Fed.

Reg. at 4597.

VOLUME 8

�187-274/Sections06

140

10/9/01

2:25 PM

Page 140

ENVIRONMENTAL ADMINISTRATIVE DECISIONS

More recently, EPA proposed a National Emissions Standards for

Hazardous Air Pollutants (“NESHAP”) rule for the fiberglass manufacturing

industry. 62 Fed. Reg. 15,228 (Mar. 31, 1997). This proposed rule would

apply to hazardous air pollutant emissions rather than PM emissions from

the forming process, but the issue of proprietary process technology was

also addressed in this context. In selecting a formaldehyde emission standard, EPA eliminated from consideration the emission level achieved at

one plant because “[t]he emission level * * * is from a proprietary forming

process not available to the rest of the industry.” Id. at 15,242.

From this background and the arguments presented in this case, we

conclude that the fiberglass manufacturing process is indeed characterized by specialized processes and raw material mixtures that vary from

firm to firm and product to product. Notwithstanding these differences,

the pollution control devices that individual companies apply are legitimate avenues of inquiry, which must be explored fully. It is therefore

appropriate to look at control technologies and emission limits at other

rotary spin plants when searching for potential control options in the first

step of the BACT determination.

We are unpersuaded by Knauf’s argument that the only facility within the fiberglass manufacturing industry that is suitable for comparison to

the proposed COSL facility is Knauf’s plant in Lanett, Alabama. While the

Lanett plant may well be the most similar to the proposed plant because

Knauf intends to use the Lanett process technology in Shasta Lake, that fact

should not foreclose Knauf’s obligation to look at its competitors’ plants in

identifying potential control options. The approach used by Knauf has the

potential to circumvent the purpose of BACT, which is to promote use of

the best control technologies as widely as possible. If a company can claim

that the only facilities similar to a proposed project are its own facilities,

this objective of the BACT program would not be fulfilled.

Petitioners raise legitimate questions about how the particular control technology and emission limits for Knauf were selected. Based on the

record information and arguments made on appeal, we cannot determine

if the particular control technology and emission limit selected for this

facility truly qualify as BACT. Answers to still open questions are needed

in order to assess AQMD’s BACT determination. For example, what control technologies are in use on the forming sections of the Owens

Corning and Schuller fiberglass plants reportedly evaluated by Knauf and

AQMD? What are their emission limits for PM10? How did Knauf and

AQMD select the number of PM10 control devices and their configuration?

Would a different configuration, similar to what is being used at

VOLUME 8

�187-274/Sections06

10/9/01

2:25 PM

Page 141

KNAUF FIBER GLASS, GMBH

141

CertainTeed’s facilities, result in a different level of emissions reduction?31

If WEPs can be designed in a variety of sizes, how did Knauf and AQMD

choose the size of the WEP for this facility? As the record stands, we cannot find that AQMD adequately considered the comments received on

the BACT issue. AQMD’s response to comments and the petitions for

review have not convinced us that the particular design of the control

technology (i.e., size and configuration of pollution control equipment)

or the selected PM10 emission limit necessarily constitutes BACT.

We are remanding the BACT determination in the interest of obtaining the benefit of further analysis on this issue. We are ordering AQMD

to prepare a supplemental BACT analysis for this proposed facility. We

suggest that the supplemental analysis employ the format described in

the NSR Manual guidance. We would therefore expect to see a list of all

control options considered, including identification of the information

source for each option. At a minimum, it appears that such a list would

include Knauf’s Lanett, Alabama facility, the three California fiberglass

facilities discussed in the permit evaluation document, and CertainTeed’s

Kansas City, Kansas facility.32 A technical feasibility analysis should be

documented for each identified control option for which there is an

infeasibility claim. Conclusions that one or more of the options are not

available or applicable need to be justified. After the technical feasibility

analysis, remaining control options should be listed in order of stringency, with the most stringent option first. AQMD should also present its

conclusions regarding the collateral environmental impacts of the top

control option and any necessary analysis of other collateral impacts (i.e.,

energy or economic). If the top option is rejected, the collateral impacts

of each subsequent control option should be documented.

The purpose of this grant of review is to provide AQMD an opportunity to correct some serious deficiencies in the record pertaining to the

31

In response to the petitions for review, Knauf supplied an engineering and cost

analysis for expanding the size of the WEP designed for the Shasta Lake facility. Knauf

Resp. Ex. 4. The analysis compares the PM10 removal and capital costs for the WEP as

designed, a 50% larger WEP, and a 100% larger WEP. Larger WEPs can achieve greater

removal efficiencies by increasing treatment time for an exhaust gas stream. Id. The WEP

as designed removes approximately 238 tons of particulate per year at a cost of $3,344,000.

The analysis shows that a 50% larger WEP will remove an additional 11.9 tons of particulate per year at an additional capital cost of $1,361,000. A 100% larger WEP can remove

19.1 additional tons of particulate at an additional cost of $2,721,000. Id. A similar analysis

could have provided a basis for comparing the WEP as designed with a multiple WEP

design, as used at CertainTeed.

32

These are the facilities for which there is some documentation in the record. See

supra Table 1. To the extent that other facilities or information sources were considered or

are considered in the course of the remand, those should also be included in the list.

VOLUME 8

�187-274/Sections06

142

10/9/01

2:25 PM

Page 142

ENVIRONMENTAL ADMINISTRATIVE DECISIONS

BACT determination. The petitioners’ arguments regarding WEP design

and the PM10 emission limit are legitimate questions that were rejected

without adequate explanation. Thus, the PM10 BACT determination for the

proposed Knauf facility is clearly erroneous because the analysis of control options was incomplete. Incomplete BACT analyses are grounds for

remand. See In re Masonite Corp., 5 E.A.D. 551, 568–69, 572 (EAB 1994)

(remand of PSD permit in light of incomplete analyses in BACT determination); In re Brooklyn Navy Yard Resource Recovery Facility, 3 E.A.D.

867, 875 (Adm’r 1992) (PSD permit remanded for failure to adequately

consider viability of measures suggested by petitioner for reduction of

NOX emissions).

In ordering a remand on BACT, it is also appropriate to provide a

few clarifying comments relating to particular issues raised on appeal.

First, Petition No. 98–16 suggests that Knauf should obtain and employ

CertainTeed’s manufacturing process technology in lieu of its own. While

this may be included as one of the alternatives in the first step of the

BACT analysis, this option may well turn out to be technically infeasible.

We acknowledge that there are differences in features of the manufacturing process among companies, and that such differences have historically been treated as proprietary and confidential.33 Process technologies

that are treated as proprietary and are not commercially available may be

considered technically infeasible and eliminated from the BACT consideration process. 34 Individual permit applicants and permitting authorities

ordinarily should not have to negotiate with owners of proprietary

process technologies in order to satisfy BACT requirements.

33

We accept the Agency’s characterization of confidential and proprietary process

technology used by the fiberglass industry as articulated in the standard setting context.

The national standards (i.e., NSPS and NESHAPs) are the best tools for effecting industry

wide adoption of lower emitting processes. The program offices in charge of developing

such standards are better equipped than we are to assess confidentiality claims regarding

process technology.

34

We believe that the commercial availability test is the proper way to deal with proprietary and confidential technologies rather than an inquiry into redefining the source. A

request to redefine a source presumes that an alternative (and lower-polluting) process is

available. Here, it is not clear that lower-polluting processes are available to Knauf

(although that is a legitimate area of inquiry in preparing a supplemental BACT analysis

on remand). Even if such processes are not available, however, Knauf and AQMD are not

exempt from fully investigating available add-on pollution controls.

We reject AQMD and Knauf’s argument regarding redefining the source to the extent

that they seek to avoid performing and/or documenting a BACT analysis that considers

pollution control options used by their competitors. While we are not requiring Knauf to

pursue its competitors’ trade secrets, we do expect serious consideration of pollution control designs for other facilities that are a matter of public record.

VOLUME 8

�187-274/Sections06

10/9/01

2:25 PM

Page 143

KNAUF FIBER GLASS, GMBH

143

Second, at some point in the BACT analysis, AQMD should take into

account and discuss any difference in the numerical emission limits due

to the application of a particular control option to the Knauf plant. A particular control technology may be available and applicable but the specific numerical emission limit achievable by Knauf may not be the same

limitation achieved elsewhere. To the extent that the emission limit difference is a matter of technical feasibility, this issue falls under step two

of the BACT analysis as outlined in the NSR Manual. To the extent that a

different limit is justified due to collateral energy, economic, or environmental considerations, the issue falls under step four. Due to characteristics of individual plant processes, we recognize that application of identical technology may not yield identical emission limits. However, the

BACT analysis should contain a comparison of these limits and provide

an explanation for the differences.

The conclusion of AQMD’s supplemental response regarding BACT

may be that the emission limits and control technology currently required

by the permit still constitute BACT. Alternatively, AQM