\\Server03\productn\M\MAT\17-2\MAT207.txt

unknown

Vol. 17, 2001

Seq: 1

27-SEP-02

Stock Options

13:44

275

Stock Options: A Significant but

Unsettled Issue in the Distribution

of Marital Assets

by

Robert J. Durst, II‡

I. Introduction

A dramatic change has occurred in the components of executive compensation over the past 15 years. In 1985, 60% of a

corporate executive’s total compensation was base salary, 20%

was short-term incentive payments and 20% was long-term incentive payments. By 2000, that mix had shifted so that only

20% of a corporate executive’s compensation was base salary

and 80% was attributed to short-term and long-term incentive

payments.

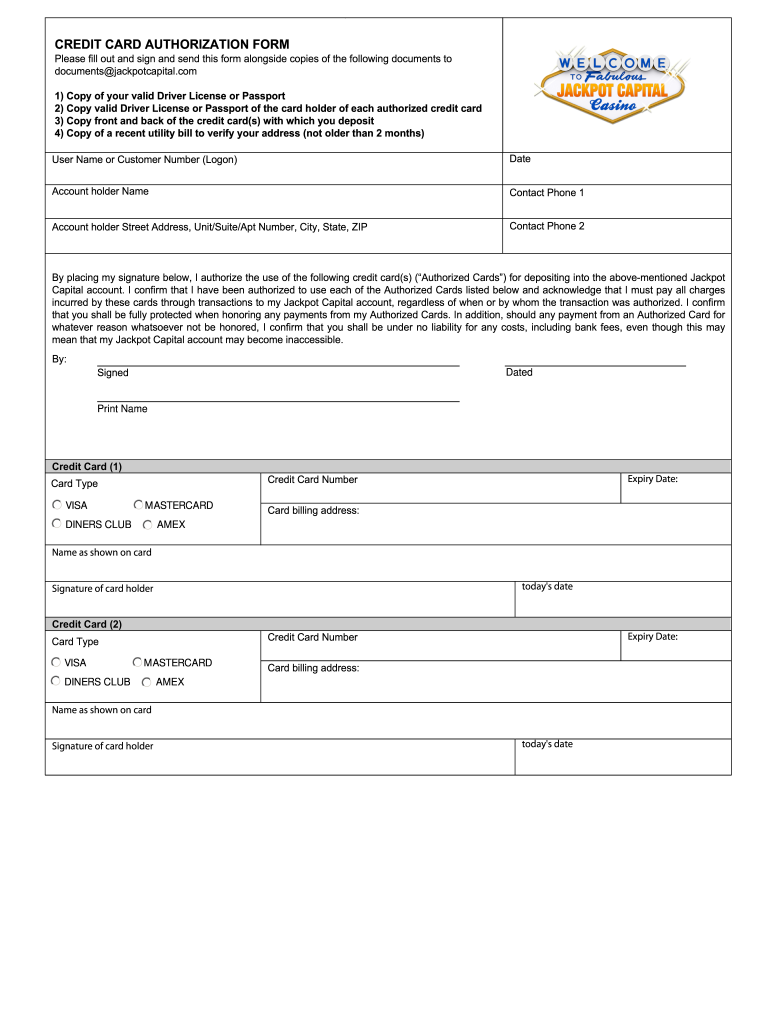

Shown graphically, the shift is as follows:

Executive Compensation:

Changing Mix of Elements

Component:

Base Salary

ST Incentive

LT Incentive

1985

60%

20%

20%

1990

50%

25%

25%

1995

35%

25%

40%

2000

20%

25%

55%

TOTAL

100% 100% 100% 100%1

Stock based programs,2 particularly stock options, have long

been a key component of short-term and long-term incentive

‡ Robert J. Durst, II, is a Shareholder in the Law Firm of Stark & Stark,

Princeton, New Jersey. This paper was originally prepared for presentation at

the 2000 “Masters Forum of Family Law,” NJ Institute for Continuing Legal

Education.

1 Based upon data compiled by Paul R. Dorff, APD, Managing Director

of Compensation Resources, Inc. 310 Route 17 N., Upper Saddle River, New

Jersey 07458.

2 In addition to stock options, restricted stock programs which are an

outright grant of corporate stock to an employee with restrictions as to its use,

sale or transfer; stock bonuses pursuant to which all or a portion of employee’s

�\\Server03\productn\M\MAT\17-2\MAT207.txt

unknown

Seq: 2

27-SEP-02

13:44

276 Journal of the American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers

compensation for upper level corporate executives. In recent

years, not only has the use of stock options as a component of

compensation increased, it has been extended well beyond the

executive level employees to employees of all levels, including

middle management and even non-management personnel.3

Recent articles address the increasing use of stock options as

a component of employee compensation.4 IBM, for instance, has

made a substantial break with its former policy and expanded

“stock option programs to a wider group of employees - namely

non-executives.”5 IBM President, Louis Gerstner, identified a

need to offer an expanded group of employees long-term

incentives to prevent them from being wooed by smaller hightech companies which typically offer significant stock or stock

option incentives as sign-on or compensation bonuses. Experts

state that IBM had “to halt the brain drain and give employees

an incentive to stay with the company.”6

A growing number of corporate employers, particularly

technology companies, are granting their employees stock

options in lieu of large pay checks. Start-up and under

capitalized companies can reduce their payroll costs by giving the

employees a stake in the company’s future through the issuance

of stock options.7

annual bonus is paid in company stock; contingent stock which is an award of

stock which takes on value in the event of a contingency (usually a public

offering of the stock); or, stock appreciation rights whereby the employee is not

awarded the stock itself, but rather a right to the appreciation in the value of

the company stock are other common forms of executive compensation. While

some of the legal issues applicable to stock options may be the same or similar

to the issues presented by these programs, each of these programs also may

present their own unique factual and legal issues in the context of the

distribution of marital assets which are not addressed in this paper.

3 Dr. Frank D. Tinari, Professor of Economics, Seton Hall University,

South Orange, New Jersey, in release of Tinari Economics, dated January, 2000.

4 Ira Sager, Stock Options: Lou Takes a Cue from Silicon Valley,

BUSINESS WEEK, Mar. 30, 1998, at 34, Sana Siwolop, More Fired Workers Are

Suing for Stock Options, NEW YORK TIMES, Nov. 21, 1999, at 11, Brian J. Hall,

What You Need to Know About Stock Options, HAR. BUS. REV., Mar./Apr.,

2000.

5 Sager, supra note 5, at 34.

6 Id.

7 Siwolop, supra note 5, at 11. Employees holding stock options who feel

that they have been discriminated against or have been wrongfully fired are

�\\Server03\productn\M\MAT\17-2\MAT207.txt

Vol. 17, 2001

unknown

Seq: 3

Stock Options

27-SEP-02

13:44

277

Stock options are being used as:

1. A component of current and future compensation for

start-up companies that cannot afford large cash payrolls;

2. A method of retaining employees who may otherwise be

subject to raiding by competitors; or

3. A method of increasing future, long-term motivation (i.e.,

enhanced performance) by employees.

The business community has comprehensively analyzed the

issues that stock options may create in the context of corporate

compensation. In contrast, the matrimonial courts have had an

insufficient number of cases submitted to them to address a

myriad of issues that stock options can present in the context of

the distribution of marital assets at the time of a divorce.8

The purpose of this article is to address the issues of defining

stock options, discussing alternative valuation methodologies,

and offering practice points for handling stock options in the

context of marital litigation.

II. Glossary

Fundamental to an understanding of stock options is an understanding of the nomenclature to understand the options themselves and to interpret and apply the cases that have been

decided to date. An assumption is often made that “all options

are created equal.” In fact, stock options vary significantly in

their fundamental nature, their economic implications, their

characteristics, and their tax implications. To understand the

fundamental differences in the various types of stock options, the

following basic terminology must be understood:

A. Incentive Stock Option (ISO)

An ISO is an Internal Revenue Service qualified stock option, whereby the employee may purchase stock at a specified

price usually over a period not to exceed ten years, with the requirement that the stock must then be held for at least one year

now seeking redress not just for their lost wages, but for the value of their lost

stock options.

8 As will be discussed subsequently, New Jersey, a highly corporate state,

has only two reported decisions and one unreported decision addressing stock

options. See infra text accompanying notes 13-14.

�\\Server03\productn\M\MAT\17-2\MAT207.txt

unknown

Seq: 4

27-SEP-02

13:44

278 Journal of the American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers

after exercise or two years after the stock option grant. An ISO

is not taxed to the employee when granted or when exercised.

Only the appreciation (the increase of stock price over the exercise or strike price) is taxed at the capital gains rates upon sale of

any stock acquired by use of the option.

B. Non Qualified Stock Option (NQSO)

An NQSO is a stock option that does not meet the Internal

Revenue Service criteria for an ISO.9 The principal difference

between an ISO and NQSO is that with an NQSO the employee

is not taxed at the time of the grant of the option (the same as in

the case of an ISO), but an ordinary income tax is assessed when

the option is exercised. Unlike the ISO, at the time of exercise

the appreciation from the exercise or strike price to the then

market value is taxed at an ordinary income rate. If the acquired

stock is sold thereafter, like the ISO, a capital gains tax applies to

the appreciation in the value of the stock from the date of exercise to the date of sale.

C. Exercise Price or Strike Price

The terms exercise price or strike price are used interchangeably. The exercise or strike price is the price at which the

employee may purchase the stock under the terms of the option

agreement.

D. Market Price

The market price is the market value of the stock. For publicly traded companies, the market value is the reported trading

value (e.g., NYSE and NASDAQ). For non-publicly traded companies, the market value could arguably be the book value or a

forensically determined value using accounting or a valuation

formulae and theorems. The market price is relevant not only

for determining the “intrinsic value” of the stock option, but also

for determining the ordinary income tax imposed at the date of

9 The matrimonial practitioner seldom, if ever, has to make a judgment

whether a particular stock option is an ISO or an NQSO. The stock option

agreements themselves and the SEC Prospectus issued by the company for the

stock option program will define whether or not the particular program is an

ISO or an NQSO.

�\\Server03\productn\M\MAT\17-2\MAT207.txt

Vol. 17, 2001

unknown

Seq: 5

Stock Options

27-SEP-02

13:44

279

exercise for an NQSO and the capital gains tax that will be imposed at the time of sale of the acquired stock for either an ISO

or a NQSO.

E. Intrinsic Value

The intrinsic value of the stock option is the difference between the exercise or strike price and the market price.

F. Vesting Period

The vesting period is the period of time which the employee

must wait before exercising the option. Most options have a

scheduled vesting period. For example, the options will vest at

the rate of 10% per year for 10 years or 20% per year for five

years.

G. Expiration Date

The expiration date is the date after which the employee

loses the right to exercise the option.

H. Cashless Exercise

Pursuant to the Federal Reserve Board and Securities and

Exchange Commission regulations and approval, stock options

may be exercised through a margin transaction in which no cash

is exchanged. The option is exercised on margin, the acquired

stock is immediately sold, the margin loan is repaid and the remaining proceeds are paid over to the employee.10

I. Underwater Option

An underwater option is an option for which the market

price is less than the current exercise or strike price.

10 To the extent the use of marital funds may be a relevant factor in determining whether a stock option and/or the proceeds from the subsequent sale of

stock acquired pursuant to the option is marital property or determining the

appropriate percentages of distribution of the proceeds from the sale of the

stock, the use or non-use of marital funds for the purpose of exercising the

option may be of some significance.

�\\Server03\productn\M\MAT\17-2\MAT207.txt

unknown

Seq: 6

27-SEP-02

13:44

280 Journal of the American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers

III. The Three Step Process for the Distribution

of Marital Assets.

The distribution of assets at the time of a divorce involves

three basic steps.

1. The assets which were “acquired during the marriage”

must be identified.

2. The assets acquired during the marriage must be valued.

3. The assets acquired during the marriage must be fairly

allocated or distributed.11

The distribution of stock options at the time of a divorce is

no exception to this three step process. However, the very nature, the specific characteristics, and the many variables in the

nature and timing of the stock option awards has and will continue to raise myriad issues regarding the implementation of

what may appear to be a rather simple three step process.

A. STEP 1: Was The Stock Option Acquired During The

Marriage?

Generally, the operative period for the acquisition of marital

assets is the period of time from the date of the marriage to the

date of separation, the date of filing the complaint, or another

terminating date defined by state statute or case law.12 In the

context of stock options, multiple factual alternatives can arise

regarding whether a stock option was “acquired during the marriage.” Consider, for example, the following factual variations

(using the date of filing of the divorce complaint as the ending

date for the acquisition of assets subject to distribution).

11

Alan M. Grosman, New Jersey Family Law, § 9.2, 236 (1999); Skoloff &

Cutler, New Jersey Family Law Practice, N.J. ICLE, § 1.5A(1), 1-157 1999;

Rothman v. Rothman, 320 A.2d 496 (N.J. 1974).

12 Painter v. Painter, 320 A.2d 484 (N.J. 1974). Although the courts have,

where deemed appropriate, advanced the commencement of the acquisition period for assets acquired “in contemplation of the marriage” or extended the

“cut off date” beyond the filing of the divorce complaint when equity required.

See, e.g., Pascale v. Pascale, 660 A.2d 485 (N.J. 1995).

�\\Server03\productn\M\MAT\17-2\MAT207.txt

Vol. 17, 2001

unknown

Seq: 7

27-SEP-02

Stock Options

13:44

281

1. The option is granted prior to the marriage, was

unvested at the time of the marriage, and vests

during the marriage.

Under this scenario, the employee/recipient of the option may argue

that the option was acquired prior to the marriage and is, therefore,

exempt from equitable distribution. The nonemployee spouse may argue that the option was of no value until it was vested, that it vested

during the course of the marriage and that marital efforts went into

vesting the option.

2. The option is granted during the marriage, was unvested

at the date of the complaint, and will vest over a

period of time subsequent to the complaint.

Under this scenario, the nonemployee spouse might make an argument contrary to that of the nonemployee spouse in scenario 1. In this

scenario, the nonemployee spouse would argue that the option was

“acquired” (i.e., granted) during the marriage and is, therefore, subject to equitable distribution. The fact that it will vest over a period of

time subsequent to the marriage would be irrelevant.13

3. The option is granted shortly after the marriage, but the

employee spouse argues that it was granted for past

performance that pre-dated the marriage.

Again, unlike the nonemployee spouse in scenario 1, the nonemployee

spouse in this case would argue that the option was acquired during

the marriage because it was granted within the marital period and that

the past performance argument is irrelevant.14

4. The option is granted after the filing of the complaint for

divorce.

Similar to scenario 1, the employee/recipient spouse would argue that

the option was outside the duration of the marriage and the nonemployee spouse would argue that it is nonetheless subject to equitable

distribution because it was for performance and efforts expended during the marriage.15

13 See, e.g., Green v. Green, 494 A.2d 721 (Md. Ct. Spec. App. 1985),

Lomen v. Lomen, 433 N.W.2d 142 (Minn. Ct. App. 1988), Cohen v. Cohen, 937

S.W.2d 823 (Tenn. 1996), and cases cited in Cohen for examples of this fact

pattern.

14 See, e.g., Demo v. Demo, 655 N.E.2d 791 (Ohio Ct. App. 1995).

15 See, e.g., Pascale, 660 A.2d 485.

�\\Server03\productn\M\MAT\17-2\MAT207.txt

unknown

Seq: 8

27-SEP-02

13:44

282 Journal of the American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers

5. The option is granted at or about the time of the

complaint for divorce but is alleged to be in

exchange for prior options that were forfeited

by the employee/recipient.

This scenario most often occurs when one spouse is recruited to a new

position at or about the time of the complaint for divorce. As a consequence of leaving prior employment, unvested options are forfeited.

To offset or compensate for the forfeiture of those options, the new

employer grants the spouse stock options. The nonemployee spouse

would argue that the new options are simply a replacement of options

that had previously been acquired during the marital period and were

otherwise subject to equitable distribution. The employee/recipient

spouse would argue that the nonemployee spouse has contributed

nothing to the value of the options that were acquired at or about the

time of the filing of the divorce complaint and that vesting of those

options requires the continued (post-complaint) work performance.16

B STEP 2: What Is The Value Of The Stock Options?

The threshold question at this step of the process is: Does a

stock option have a value in excess of its intrinsic value? Intrinsic value is simply the difference between the exercise or strike

price and the market value of the stock.17 The academic, accounting, Internal Revenue, and “marketplace” communities all

seem to have concluded that the real value of a stock option may

not simply be its intrinsic value. In the event of a present value

off-set distribution of other assets to the non-employed spouse

instead of a deferred division the options must be valued.18

16

Although beyond the scope of this article, query whether there is or

should be a concept of “executive good will” which may be relevant and applicable to factual scenarios such as this. If at or near the end of a marriage, one

of the spouses is recruited to a new company with a significantly increased earning capacity or benefits package, can the nonemployee spouse make an argument that the employee spouse’s increased fortunes are a result of “executive

good will” which was developed and built up during the course of the marriage

as a result of their joint marital efforts. Such an argument is similar to the

manuscript which is “written and in the drawer” but not yet published at the

date of the divorce complaint argument.

17 See supra text at II E.

18 For a discussion of present or deferred distribution of contingent assets,

see Kikkert v. Kikkert, 427 A.2d 76 (N.J. Super. Ct. App. Div. 1981), in which

the court held that when the trial court is satisfied that a present value can be

established, and other assets exist against which an offset can be made, a final

�\\Server03\productn\M\MAT\17-2\MAT207.txt

Vol. 17, 2001

unknown

Seq: 9

Stock Options

27-SEP-02

13:44

283

1. Academic

In 1973, Professors Fischer Black and Myron Scholes developed the “Black-Scholes Model” for valuing stock options for

which they were awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1977.

The Black-Scholes Model is generally accepted, but remains a

highly complex method for valuing stock options – taking into

account and mathematically modeling five fundamental factors:

a.

b.

c.

d.

e.

The time to the expiration of the option;

The strike price;

The market price of the underlying stock;

The volatility of the underlying stock; and

The risk-free interest rate.

Although the Black-Scholes Model remains the fundamental

method of calculating the value of a stock option in the economic

and mathematical communities, it is difficult to understand, complex to apply, and, arguably, of limited value in the marital

context.19

2. Accounting

The accounting profession had a need to determine the

value of stock options for corporate accounting and reporting

purposes and has developed a protocol for doing so. The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) issues Accounting

Principle Board Opinions and Statements (APBO) and Statements of Financial Accounting Standards (SFAS) for guidance of

the accounting profession. In 1984, an APBO established the accounting standards to be used for estimating the fair value of a

division of the assets should be made. On the other hand, if no other assets are

available to offset the present value of the deferred asset and/or the present

value of the deferred asset cannot be sufficiently established, the court should

“resort” to deferred distribution. Later in Whitfield v. Whitfield, 535 A.2d 986

(N.J. Super. Ct. App. Div. 1987), while recognizing that the Kikkert court found

the immediate offset method to be “preferable,” the court concluded that absent the consent of the parties, a litigant should not be mandated to make immediate distribution of an asset which is not vested, is contingent or might

never be received.

19 In Wendt v. Wendt, No. FA96-0149562-S, 1988 WL 161165 (Conn.

Super. Ct. Mar. 31, 1998), the trial court judge rejected the use of the BlackScholes model for valuing stock options stating that it is “not an appropriate

method of evaluating employment issued unvested stock options in a marital

setting” and finding that the model “showed significant errors.” Id. at 197, 198.

�\\Server03\productn\M\MAT\17-2\MAT207.txt

unknown

Seq: 10

27-SEP-02

13:44

284 Journal of the American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers

stock option.20 However, by 1993, the FASB recognized the

need to revisit its stated procedures for valuing stock options and

issued SFAS No. 123 to replace APBO No. 25. In issuing SFAS

No. 123, the Financial Accounting Standards Board recognized

that simply using the intrinsic value for the stock option often

failed to recognize the true value or cost of the stock option and,

therefore, ran the risk of creating corporate financial statements

that did not accurately reflect the value of or the corporation’s

cost of stock options.21 SFAS No. 123 states that a company

must measure the actual fair value of a stock option without discount for vested or nonvested considerations, and without discount for non-transferability; it observes that in most instances,

the actual fair value of the option would exceed the intrinsic

value.22

3. Internal Revenue Service

In 1998, the Internal Revenue Service addressed the need to

determine the value of stock options for estate and gift tax valuation purposes.23 The IRS essentially adopted the Black-Scholes

model.

4. The Marketplace

The marketplace itself regularly fixes a value for the public

sale and purchase of stock options.24 Dr. Les Barenbaum cited

the actual May 24, 1999, Wall Street Journal listings for Dell stock

options expiring in January, 2000 and January, 2001 to demonstrate the reality that the market place values stock options in

20 Financial Accounting Standards Board, Accounting Principle Board

Opinion, No. 25. (1984).

21 Financial Accounting Standards Board, Accounting Principle Board

Opionion, No. 123 (1993).

22 See Reva B. Steinberg, Take Stock of Your Options – Understanding the

New Accounting Rules for Stock Based Compensation, 10 INSIGHTS 24 (May

1996). Ms. Steinberg is the Director of Accounting Research for Ten Eyck Assoc., Inc., King of Prussia, Pennsylvania.

23 I.R.S. Rev. Proc. 98-34, 1998 WL 167549.

24 Unrestricted stock options are regularly traded and have published values. It should be noted, however, that most, if not all, executive compensation

stock option programs involve restricted stock options, meaning that they cannot be traded or transferred by the recipient employee, there are vesting schedules and there may be exercise restrictions.

�\\Server03\productn\M\MAT\17-2\MAT207.txt

Vol. 17, 2001

unknown

Seq: 11

27-SEP-02

Stock Options

13:44

285

excess of the intrinsic value.25 As can be seen from the following

table, the Dell options expiring in January, 2001, were actually

“underwater” as of May 24, 1999. The intrinsic value was zero

(or more correctly, minus 12.628) yet the option was trading at a

price of $8.75. The other two options (January, 2000 and January, 2001) had intrinsic values of only $7.31, but were trading at

$11.75 and $15.75, respectively.

Stock

Price

Firm

Expiration

Date

Striking

Price

Option

Value

Intrinsic

Value

$37.3125

$37.3125

$37.3125

Dell

Dell

Dell

January, 2001

January, 2000

January, 2001

$50.00

$30.00

$30.00

$8.75

$11.75

$15.75

$0

$7.31

$7.31

Thus, the marketplace recognizes an opportunity value of

options in excess of and distinctly different from simply the

intrinsic value of the option.

If the process of distributing assets includes determining the

“fair market value” of the assets as the second step in the

equitable distribution process an argument can be made that the

courts should look to the market itself to determine the “fair

market value of stock options” as opposed to the mathematical

model of Black-Scholes.26

5. Applications of Discounts

a. Insider trading restrictions

In some cases, the option holder is a person who would be defined as an “insider” under SEC Regulations. Under SEC Regulations, an insider has limited periods within which that person

can trade the company stock or exercise a company’s stock options. The purpose of the restrictions is to prevent insiders from

capitalizing on information that they have obtained in their capacity as corporate executives, but which has not yet been dis25

Dr. Barenbaum is a principal in the firm of Kroll, Lindquist & Avey

and a Professor of Finance at LaSalle University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Dr. Barenbaum illustrated the principle that stock options may have a value in

excess of their intrinsic value by using the actual Wall Street Journal listings for

Dell Stock on May 24, 1999. Les Barenbaum, Intrinsic Value (1999 unpublished

manuscript on file with author).

26 Rothman v. Rothman, 320 A.2d 496 (N.J. 1974).

�\\Server03\productn\M\MAT\17-2\MAT207.txt

unknown

Seq: 12

27-SEP-02

13:44

286 Journal of the American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers

seminated to the public. Therefore, most insider trading

restrictions are tied to the quarterly report dates for the company; usually the “insider” can only trade in the company’s stock

or stock options immediately after (and not before) the public

release of the company’s earnings and financial statements so

that he or she and the public would have equal access to available financial information.

In addition, an “insider” is forbidden to trade within defined

periods. Such periods usually precede a substantial change of financial position by the company or a new stock offering. It

could, therefore, be argued that options held by an “insider” cannot be freely traded and/or can only be traded within confined

periods of time and are, thus, worth less than options held by a

person whose trading time is not restricted.

b. Non-transferability

Virtually all stock options have transferability restrictions. The

employee recipient cannot trade the options on an option exchange or transfer the options to any other person. Thus, there is

an argument that the options which have restricted transferability should be discounted as opposed to unrestricted options.

However, unless the restricted options in question are being valued in comparison to or against the publicly traded, unrestricted

options, it would not appear that a transferability discount would

be appropriate.

c. Deferred tax liability

By statute or case law, courts often are instructed to take into

account the tax implications resulting from equitable distribution

of marital assets and/or the tax liabilities (actual or deferred) that

may be assessed against particular assets.27 While courts often

should not take into consideration tax consequences that are

“too speculative,” depending upon the type of stock option (an

ISO or an NQSO), the tax liabilities may or may not be “speculative.” With the NQSO, an ordinary income tax may be assessed

at the time of the grant or, in some instances, at the time the

grant vests. Such a tax liability, it would seem, is certain and definable both in time and amount. On the other hand, no tax lia27

Orgler v. Orgler, 568 A.2d 67 (N.J. Super. Ct. App. Div. 1989).

�\\Server03\productn\M\MAT\17-2\MAT207.txt

Vol. 17, 2001

unknown

Seq: 13

27-SEP-02

Stock Options

13:44

287

bility attaches to an ISO until it is exercised at some unknown

time to acquire the underlying stock and the underlying stock is

sold. If the underlying stock is held for a requisite period of

time, it will be taxed at a long term capital gains rate or as ordinary income. Such tax consequences could be considered “speculative.” It could be argued that even with an ISO, at least a

capital gains tax is ultimately certain. It also could be argued that

capital gain is speculative in terms of time and amount depending

upon the recipients decision to retain or sell the stock.

C. STEP 3: The assets acquired during the marriage must be

fairly allocated or distributed.

Step three in the process of distributing marital assets does

not pose any particular problem unique to stock options except

with regard to the restrictions on their transferability.

Once the quantum and value of the options are determined,

the usual factors for determining the parties respective entitlements should be applied.28 The fact that stock options cannot

normally be transferred to an outsider (i.e., nonemployee spouse

of the employee recipient of the option) requires special handling. The New Jersey case of Callahan v. Callahan29 addressed

this problem by creating a “constructive trust” to implement the

distribution.

IV. Should a “Bright Line Rule” Exist or Would

it Create a “Serbonian Bog?”

In the highly publicized Connecticut case of Wendt v.

Wendt,30 the nonemployee spouse urged the court to establish a

“bright line rule” that would include all vested and unvested employment plans (including unvested stock options) as property

subject to marital distribution.

The trial court observed that establishing a “bright line” rule

would have obvious appeal for practitioners, clients and judges

alike, but refused to create one in family cases that require the

28

29

30

1998).

See, e.g., N.J. STAT. ANN. 2A:34-23.1 (2002).

361 A.2d 561 (N.J. Super. Ct. Ch. Div. 1976).

No. FA96-0149562-S, 1988 WL 161165 (Conn. Super. Ct. Mar. 31,

�\\Server03\productn\M\MAT\17-2\MAT207.txt

unknown

Seq: 14

27-SEP-02

13:44

288 Journal of the American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers

application of principles of equity and are “fact specific”

determinations.31

The court expressed its concern that “its decision or any decision that established a bright line determination would be read

with a great deal of interest by corporate officers” with the result

that such corporate officers could and would be able to “restructure” any corporate benefits plan in a way that would avoid any

“bright line rule.”32

Drawing upon the poetic imagery of John Milton in Paradise

Lost and the judicial humor of Justice Cardoza, the trial judge in

Wendt held that to establish a “bright line” rule would be akin to

plunging into a “Serbonian Bog.”33

The court held that:

To establish a bright line rule in the area of marital distribution of

employment benefits, where no court has tread, where the landscape

varies and the scenery is in constant change, is to take the step cautioned by Milton [and] Cardozo . . . this court will not trespass into

that area without further guidance.34

The court in Wendt also observed that equitable remedies

should not be bound by formulas, that the myriad forms of property ownership in the modern world dictate that no universal

principle can be devised to fit every case, that there are few areas

of law that are black and white and that in marital disputes the

shades of gray are particularly numerous. Therefore, the court

found that no “bright line” rule could or should be established to

define what stock options would be subject to marital distribution and how they should be distributed.35

The following review of reported decisions across the country indicates an almost universal concurrence with the trial

court’s observations in Wendt. However, these holdings vary

widely regarding some specific questions as to division of stock

31

Id. at *154.

Id. at *156.

33 John Milton, in Paradise Lost, book 2, referred to the “Serbonian Bog”

as a “gulf profound betwixt Damiata and Mount Casins, where whole armies

have sunk.” Justice Cardozo is attributed with first using the reference to

Milton’s “Serbonian Bog” in a legal decision, Landress v. Phoenix Mutual Life

Ins. Co., 291 U.S., 491, 499, where he referenced the attempt to distinguish between accidental results and accidental means as a plunge into a Serbonian Bog.

34 Wendt, 1998 WL 161165, at *155.

35 Id. at *145.

32

�\\Server03\productn\M\MAT\17-2\MAT207.txt

Vol. 17, 2001

unknown

Seq: 15

27-SEP-02

Stock Options

13:44

289

options in marital dissolution. The cases demonstrate that

“bright line” rules do not exist as to:

1. What stock options should be considered marital property and, therefore, subject to equitable distribution; or

2. How stock options (or the value thereof) should be divided between marital litigants; or

3. How the varying factual differences between the nature

of the particular options, the timing of the party’s receipt of the

options and the vesting characteristics of each option affects that

party’s marital distribution.

A review of the cases across the country indicates that the

distribution of stock options is driven more by the equities and

underlying facts of the particular case than enunciated principles

of law.

V. The Multiple Approaches of the Existing

Case Law

No states have held (nor presumably will ever hold) that a

stock option that was granted and that has become vested during

the marriage is not subject to marital distribution. The issues

arise with regard to options granted before or after the marriage

or options that are not vested at the time of termination of the

marriage.36

A. Granted But Unvested Stock Options

Several states have held that stock options granted during

the marriage, but unvested at the date of the complaint for divorce, do not constitute assets subject to marital distribution. Indiana, North Carolina, and Oklahoma are such states. The court

in Hann v. Hann37 held that the unvested options that were subject to forfeiture in the event of the employee’s death or termination of employment were contingent and speculative in nature

and, therefore, not subject to equitable distribution. It should be

noted that the Hann court apparently analyzed unvested stock

36 Thus, cases that raise factual issues as to whether the asset was acquired (i.e., does its vested or nonvested status affect whether or not it was

“acquired”) and whether it was acquired “during the marriage.” See supra Section III.

37 655 N.E.2d 566 (Ind. Ct. App. 1995).

�\\Server03\productn\M\MAT\17-2\MAT207.txt

unknown

Seq: 16

27-SEP-02

13:44

290 Journal of the American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers

options in the context of an Indiana statute which excludes unvested pension benefits from equitable distribution.

In Hall v. Hall,38 the North Carolina Court of Appeals held

that inasmuch as unvested options could be lost as a result of

events occurring after the date of the divorce, they could not be

treated as marital property. The Hall court referred to a North

Carolina statute which provided that “nonvested pension, retirement and deferred compensation rights shall be considered separate property” for the purposes of marital distribution.39

Ettinger v. Ettinger40 was a case in which a wife was denied a

share of unvested stock options. However, the case seemed to

turn more on unique provisions of Oklahoma marital property

law and a res judicata issue than a substantive analysis of the

stock options themselves.

A number of the jurisdictions that have considered whether

an option granted during the marriage but unvested at the date

of the complaint for divorce is subject to equitable distribution

have held that unvested options constitute assets that are subject

to marital distribution. Maryland, New Mexico, Oregon, Pennsylvania,Tennessee, and Wisconsin all seem to have cases that

squarely stand for the proposition that options which are unvested at the termination of the marriage are subject to marital

distribution.41

Pascale v. Pascale42 has been cited to support the proposition

that stock options, which are unvested at the date of the filing of

the complaint for divorce, are subject to equitable distribution.

However, a closer reading of Pascale suggests that the court focused more on the timing of the grant in relationship to the filing

of the complaint for divorce and the possibility that an employee

could file a divorce complaint prior to and in anticipation of receiving a grant of stock options rather than having done an anal38

363 S.E.2d 189 (N.C. Ct. App. 1987).

N.C. GEN. STAT. § 50-20(b)(2) (2001).

40 637 P.2d 63 (Okla. 1981).

41 Green v. Green, 494 A.2d 721 (Md. Ct. Spec. App. 1985), Garcia v.

Mayer, 920 P.2d 522 (N.M. Ct. App. 1996), In re Powell, 934 P.2d 612 (Or. Ct.

App. 1997), Fisher v. Fisher, 769 A.2d 1196 (Pa 2001), Cohen v. Cohen, 937

S.W.2d 823 (Tenn. 1996), Chen v. Chen, 416 N.W.2d 661 (Wis. Ct. App. 1987).

42 660 A.2d 485 (N.J. 1995).

39

�\\Server03\productn\M\MAT\17-2\MAT207.txt

Vol. 17, 2001

unknown

Seq: 17

Stock Options

27-SEP-02

13:44

291

ysis of the vested versus unvested, past-performance versus

future efforts substantive issues.

B. The Coverture Fraction Approach.

In In re Marriage of Hug,43 California, a community property state, has attempted to develop a coverture fraction approach to the distribution of stock options. A coverture fraction

consists of the numerator which is the period of months between

the commencement of the spouse’s employment by the employer

and the date of separation of the parties and the denominator

which is the period of months between the commencement of

employment and the date when each option is exercisable.

Two years later in In re Marriage of Nelson,44 the court decided that the Hug fraction appeared to reward past services too

generously and gave insufficient recognition to future increases

in value of the stock. It therefore modified the numerator of the

coverture fraction to represent the number of months from the

date of grant of each option to the date of the parties’ separation

and the denominator to represent the number of months from

the time of the date of each grant to the grant’s date of

exercisability.

Within another few months, in In re Marriage of Harrison,45

the court again modified the coverture fraction to take into account the date upon which an unvested option became fully

vested. Finally, in In re Marriage of Walker,46 the California

Court of Appeal, after reviewing the Hug, Nelson, and Harrison

coverture fractions, observed that “[n]o single rule or formula is

applicable to every dissolution case involving employee stock options. Trial courts should be vested with broad discretion to fashion approaches which will achieve the most equitable results

under the facts of each case.”47

Thus, while striving mightily to craft a coverture fraction

that could be consistently applied to the apportionment of vested

43

154 Cal. App. 3d 780 (1984).

177 Cal. App. 3d 150 (1986).

45 179 Cal. App. 3d 1216 (1986).

46 216 Cal. App. 3d 644 (1989).

47 Id. at 650, citing Hug, 154 Cal. App. 3d at 792. This language resembles

Wendt’s rejection of a “bright line” rule. See supra text accompanying notes 3338.

44

�\\Server03\productn\M\MAT\17-2\MAT207.txt

unknown

Seq: 18

27-SEP-02

13:44

292 Journal of the American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers

and unvested stock options, the California Court of Appeal

seems to have come full circle, realizing that no single formula

can be devised and finding that courts should determine each

case on its own equities.

C. The Multi-tiered Approach

Beginning with In re Marriage of Miller,48 Colorado, then

New York, Minnesota and New Hampshire, have adopted what

has been referred to as the “multi-tiered method” of determining

what portion of a stock option is marital property and how that

portion should be distributed between the parties. The Miller

court addressed the issue whether stock options will typically

have elements that are compensatory for past services and elements that are incentive for future services and, thus, will require

a continuation of efforts by a party beyond the termination of the

marriage.49

The Miller court used a four step approach:

(1) The number of shares granted, whether traceable to past

or future services is to be determined.

(2) If any portion of the stock option is found to be intended

as compensation for past services, it is deemed to be marital

property fully subject to equitable distribution to the extent that

the past services were rendered during the term of the

marriage.50

(3) If any portion of the stock option is found to be intended

as an incentive for future services, it is subjected to a coverture

fraction reduction. The numerator of the fraction is the number

of months from the date of the grant to the date of the filing of

the complaint for divorce; the denominator is the number of

months from the date of the grant to the date of its

exercisability.51

(4) The portions found to be marital property pursuant to

steps two and three are then to be divided between the spouses,

48

915 P.2d 1314 (Colo. 1996).

Id.

50 Although not specifically discussed, it can be implied from the Miller

opinion that if the past services pre or post dated the marriage, the court would

have used a coverture fraction to apportion the value of those options.

51 In Re Marriage of Nelson, 177 Cal. App. 3d 150, 155, discusses the

coverture fraction.

49

�\\Server03\productn\M\MAT\17-2\MAT207.txt

Vol. 17, 2001

unknown

Seq: 19

Stock Options

27-SEP-02

13:44

293

utilizing the otherwise applicable principles of law governing equitable distribution52 and considering the facts of the particular

case.

Citing Miller with approval, the New York Court of Appeal

in DeJesus v. DeJesus53 held that “a Miller type analysis best accommodates the twin tensions between portions of stock plans

acquired during the marriage versus those acquired outside the

marriage and stock plans which are designed to compensate for

past services for those designed to compensate for future circumstances.”54 Similarly, in Lomen v. Lomen,55 the Minnesota appellate court distinguished a prior Minnesota case in which the

options had been found to have been granted solely for future

services, Salstrom v. Salstrom,56 and used a Miller-type multitiered approach. Most recently, the New Hampshire Supreme

Court held that a trial court must consider what portion of the

unvested stock options were attributable to services rendered

during the marriage (and therefore marital) and what portion

was intended to be an incentive for post-divorce services.57

D. Valuation of Options and the Option of a Constructive Trust

Several miscellaneous cases deal with specific, if not unusual

factual issues concerning stock options. For example, Goodwyne

v. Goodwyne58 is a case that involved an “underwater” option.

At the time of the divorce, the stock option had no intrinsic value

and the court imposed a constructive trust and deferred distribution to a post-judgment proceeding which was conducted when

the options had developed a value.

52

In New Jersey, presumably, the statutory criteria set forth in N.J. STAT.

ANN. § 2A:34-23 (2002).

53 687 N.E.2d 1319 (N.Y. 1997).

54 Id. at 1323.

55 433 N.W.2d 142 (Minn. Ct. App. 1988).

56 404 N.W.2d 844 (Minn. Ct. App. 1987).

57 In Re Valence, 2002 WL 97-951, May 7, 2002.

58 639 So.2d 1210 (La. Ct. App. 1994).

�\\Server03\productn\M\MAT\17-2\MAT207.txt

unknown

Seq: 20

27-SEP-02

13:44

294 Journal of the American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers

E. New Jersey Cases

The two most frequently cited New Jersey cases with regard

to stock options are Pascale v. Pascale59 and Callahan v. Callahan.60 There is also the 1999 unreported Appellate Division decision in Klein v. Klein.61 Callahan imposed a constructive trust

for the purpose of implementing the non-employee spouse’s portion of the stock options given the inability of the court to effect

a transfer of the restricted stock options to the nonemployee

spouse.

With all due respect to the trial judge in Callahan and the

Supreme Court in Pascale, neither of these cases offers much on

the substantive issues regarding stock options. As noted above,

59 644 A.2d 638 (N.J. Super. Ct. App. Div. 1994), aff’d in part and rev’d in

part, 660 A.2d 485 (1995).

60 361 A.2d at 561 (N.J. Super. Ct. Ch. Div. 1976).

61 No. A-5019-97T1, (N.J. Super. Ct. App. Div. June 24, 1999). In addition to Klein v. Klein, two unreported New Jersey Appellate Division decisions

touch upon the distribution of stock options. Allex v. Allex, No. A-5739-95T3

(N.J. Super. Ct. App. Div. June 26, 1997), defines the issue before the court as

“whether the disputed compensation [the stock options] was obtained as a result of efforts expended during the marriage.” Although the court defines the

determinative issue as being whether the options were granted for past or future services, its decision turns on the trial judge’s acceptance of one expert’s

opinion in that regard over the other’s. The appellate panel found that the trial

judge “was presented with two interpretations, one from each expert and he

chose to believe the Plaintiff’s expert.” The panel found that the judge had

examined the overall plan and made his findings based upon sufficient evidence

in the record and the panel, therefore, accepted the trial judge’s conclusions

that the options were granted in consideration for past (i.e., marital) employment performance without further discussion as to what would have been the

result had the trial judge found that all or a portion of the options were granted

in consideration for future services (i.e., nonmarital). Mailman v. Mailman, No.

A-2321-97T3 (N.J. Super. Ct. App. Div. May 28, 1999) involved, inter alia, the

distribution of stock options. However, the appellate decision turned upon an

interpretation of R. 4:50-1 and whether the unemployed spouse’s application to

reopen the final judgment of divorce to address the stock option was filed

within the time required by the rules. The plaintiff raised the issue that the

stock options which were given to the defendant two years after the filing of the

complaint for divorce were “legally and beneficially acquired” during the marriage. Citing Pascale extensively, the court remanded for further discovery regarding whether or not the options were acquired as a result of services

rendered during the marriage or were to encourage future services. Although

both of these cases are informative, neither specifically address nor turn upon

the conceptual issues addressed in this paper.

�\\Server03\productn\M\MAT\17-2\MAT207.txt

Vol. 17, 2001

unknown

Seq: 21

Stock Options

27-SEP-02

13:44

295

Callahan is a trial court decision in which the employee spouse

apparently argued that his stock options should be exempt from

equitable distribution “because an expenditure on his part is required to exercise the option.”62 The court almost summarily

dismissed that contention and moved to what it defined as “the

more perplexing problem” of crafting the manner of distributing

the stock options in light of the restrictions against transfer of the

stock options and the necessary expenditure of funds to exercise

the options.63

The court devised what has become known as a “Callahan

trust” whereby the employee spouse continues in ownership of

the stock options as “constructive trustee” for the benefit of the

nonemployee spouse. Under the court-imposed “constructive

trust,” the nonemployee spouse would be required to tender the

funds necessary to implement and exercise her share of the stock

options held by her ex-spouse in “constructive trust” for her.

The employee spouse would then exercise the option and the employee would then either remit the purchased stock or the proceeds from the sale of the stock to the non-employee spouse.

Perhaps the most significant point to be extracted from Callahan is found in a footnote. In footnote 1, the court comments

upon the 25% portion that was given to the nonemployee

spouse. The court acknowledges that 25% is substantially less

than the percentage applied to other assets, but explains that the

lesser percentage is appropriate due to the nature of the asset

(without defining what is meant by “the nature of”); and if the

stock price increases due to the defendant’s efforts (“albeit in

some small way”), the plaintiff should not share in that increase.64 The court does not further discuss these two very significant substantive issues regarding the marital distribution of

stock options.65

Pascale is a 29 page opinion of the New Jersey Supreme

Court, the first 26 pages of which address joint custody and child

62

Callahan, 361 A.2d 328.

Id. at 329.

64 Id. at 330 n.1.

65 The court does not expand upon these points, but the reference raises

interesting and significant questions as to what is the “nature” of a stock option

that would support a 25% distribution to the nonemployee spouse and what

does occur when an “active” increase occurs in the options value post divorce.

63

�\\Server03\productn\M\MAT\17-2\MAT207.txt

unknown

Seq: 22

27-SEP-02

13:44

296 Journal of the American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers

support issues. The last three pages of the opinion address the

stock options. In Pascale the parties had reached agreement as

to the distribution of all of the stock options awarded to the wife

by her employer during the marriage (without discussion

whether those options were vested or unvested). They further

reached agreement that a stock option granted to the wife by her

employer some thirteen months after the filing of the complaint

for divorce was not subject to equitable distribution (again without discussion whether any portion of that option may have been

intended to compensate the wife for services that she had performed for her employer during the marriage).

The only issue before the court was a stock option that was

granted to the wife approximately ten days after she filed her

complaint for divorce. The court observed that “serious mischief

could arise” from a strict application of the date of the complaint

rule and that a spouse considering filing a divorce could file her

complaint just before she expected to receive a large bonus or

commission simply to deny her spouse the benefit of that asset.66

So the court relaxed the “date of the complaint rule” to include

the option that had been granted to the wife ten days after she

had filed her complaint for divorce.

In a single concluding paragraph, the court then reversed the

Appellate Division, without significant discussion or analysis,

stating that it was “unconvinced” that 4,000 stock options were

awarded to the wife to encourage her continuation with future

efforts on behalf of the company. The court’s decision apparently turned on its conclusion that the wife “had not met her burden of proof that the efforts she expended to obtain the two

stock options awarded on November 7, 1999 were not put forth

during the marriage.”67

The unreported Appellate Division decision in Klein v.

Klein is, perhaps, the most substantive of the three New Jersey

decisions. However, for whatever reason, it has not been published and is therefore of limited precedential value.

In Klein, the court addressed a number of questions. The

court inquired whether the stock option was awarded for past

66

Pascale, 660 A.2d at 498.

Id. the court specifically referenced the requirement that a party seeking to exempt an asset from equitable distribution has the burden of proof in

that regard and went on to find that the wife had not sustained that burden.

67

�\\Server03\productn\M\MAT\17-2\MAT207.txt

Vol. 17, 2001

unknown

Seq: 23

Stock Options

27-SEP-02

13:44

297

services rendered to the employer during the marriage or as an

incentive for future work. It also asked how the fact that the

unvested options required the continuation of employment and

work effort by the employee subsequent to the divorce should be

addressed (recognizing that “there are no reported decisions in

New Jersey to define this concept to unmatured stock options”).

The court then addressed how a post-complaint increase in the

value of the options should be handled.

The trial court had apparently reviewed and analyzed the

option grant letter, the stock option plan’s terms, the annual

award of the grants and the employee spouse’s work record history and contribution to his company. The appellate court found

that the trial judge had not abused his discretion in finding, based

on the review of those documents and records, that the options in

question had been awarded to the employee spouse in recognition of his past performance rendered to the company during the

tenure of the marriage.

The appellate court in Klein also addressed the increase in

value of the stock options from the date of the complaint to the

date of trial. The trial court found that the increase in value was

“passive” and therefore the nonemployee spouse should be entitled to the increase in value.68 The appellate court affirmed the

finding of the trial court. A careful reading of Klein indicates

that the answers to the questions set forth above will depend

upon both the terms and conditions of the particular options

themselves and the facts and equities of the particular case.

VI. Post Complaint and/or Divorce Increases in

Value of Stock Options.

As mentioned above, footnote 1 in the Callahan opinion addresses (but does not resolve) the issue of a post complaint increase in the value of stock options. “If the stock price increases,

68 Under the facts of Klein, the employee spouse was an employee of a

multi-national corporation and the trial court apparently found that “there was

no evidence that the increase in value of the stock linked to the Defendant’s

personal industry. . . and that . . . the increases were the result of market

forces.”

�\\Server03\productn\M\MAT\17-2\MAT207.txt

unknown

Seq: 24

27-SEP-02

13:44

298 Journal of the American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers

this may be due, in some small way, to the Defendant’s effort, the

Plaintiff should not share in this.”69

The unreported Klein decision also addresses an increase in

the value of the options from the date of the complaint to the

date of the trial. Under general principles of marital distribution

law, New Jersey courts distinguish between a passive and an active increase in value in determining whether the increase in either premarital assets or marital assets that have increased in

value subsequent to the filing of the complaint for divorce should

be included in equitable distribution.70

It would appear from both the Callahan footnote and the

Klein opinion that the courts are suggesting that the passive versus active distinction should be applied to stock options. What

does this mean in practice? Although an argument could be

made that an individual employee may have contributed to the

increase in value in the stock of a national or multi-national company, the practical impact of the employee’s contributions is relatively de minimis in all but unusual and exceptional

circumstances. Possibly an executive of significant stature could

be argued to have actively contributed to an increase in the value

of the company stock. Such a situation would be atypical at best.

However, in the age of fast growing high-tech start-ups and

initial public offering companies with a limited number of key

employees, the issue becomes significantly more relevant. Suppose, for example, a spouse joins a start-up company at or near

the conclusion of the marriage. If a result of the employee’s post

complaint expertise, efforts, business connections or scientific

and technical know-how, the value of the stock and thus the

value of the stock options increases, should the non-employee

spouse share in such increase in value? Under the active versus

passive analysis, a strong argument can be made that s/he should

not.

69

Callahan, 361 A.2d 325 n.1.

See Scavone v. Scavone, 553 A.2d 885 (N.J. Super. Ct. 1988), aff’d, 578

A.2d 1230 (N.J. Super. Ct. 1990). See also Mol v. Mol, 370 A.2d 509 (N.J.

Super. Ct. App. Div. 1977), Scherzer v. Scherzer, 346 A.2d 434 (N.J. Super. Ct.

App. Div. 1975), cert. denied, 354 A.2d 319 (N.J. 1976).

70

�\\Server03\productn\M\MAT\17-2\MAT207.txt

Vol. 17, 2001

unknown

Seq: 25

27-SEP-02

Stock Options

13:44

299

VII. Tax Consequences of Transfers of Stock

Options

On November 1, 1999, the IRS issued IRS Field Service Advice 200005006.71 Under the facts submitted for that ruling, the

husband had been the holder of both ISOs and NQSOs. Pursuant to the judgment of divorce in Ruling 200005006, the nonemployee spouse was to receive one-half of the options. The

options were transferred directly to the nonemployee spouse.

The Internal Revenue Service ruled that because the options

were restricted while in the hands of the holder, but became unrestricted upon transfer to the ex-spouse, a taxable event had occurred. The service ruled that the option holder would be taxed

at ordinary income rates for the value of the options (the strike

price versus the market price) at the time of the transfer of the

options to the ex-spouse. It is not clear from Letter Ruling

200005006 whether the use of a “Callahan trust” also would have

triggered such a taxable event.

The IRS subsequently reversed its position with Revenue

Ruling 2002-22, issued on May 8, 2002. Consistent with Section

1041(a) of the Internal Revenue Code, the transfer of stock options is no longer a taxable event. The transferee, not the transferor, is liable for taxes upon exercise of the options.

VIII. Are Stock Options Assets or Income?

This article presupposes that stock options should be considered assets for the purposes of marital distribution in the event of

a divorce. If stock options have been granted, are vested, and

remain in existence at the date of termination of the marriage,

they would, almost certainly, be considered assets subject to distribution between the parties, but should stock options that are

unvested at the date of termination of the marriage or stock options that may be granted to the employee spouse subsequent to

the termination of the marriage be considered income?

Statistically, the composition of corporate employees’ pay

has shown a dramatic change from 60% cash or salary just fifteen

years ago to 20% today.72 Business writers suggest that corpo71

72

IRS Field Service Advice 200005006 at Tax Notes Today 25-61.

See supra text accompanying note 2.

�\\Server03\productn\M\MAT\17-2\MAT207.txt

unknown

Seq: 26

27-SEP-02

13:44

300 Journal of the American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers

rate America sees the granting of stock options as a method of

providing additional compensation to employees in a form that

may help to insure their longevity with the company or enhance

their future performance.

Therefore, should stock options that will vest or that will be

granted at a date subsequent to the termination of the marriage

be considered as income for the purposes of establishing child

support and/or alimony? The Colorado Supreme Court in

Miller73 distinguished stock options from deferred pension benefits and found that unlike pension benefits, employee stock options could be considered a component of the employee’s current

or future compensation.

The Ohio Court of Appeals seems to have the most specific

analysis of the issue. In Murray v. Murray,74 the Ohio Court of

Appeals held that unexercised stock options could be used in

computing a payor’s income for the purposes of calculating child

support. In Murray, the trial court had found that the options

were “the single most important element” of the employee’s

complete compensation package.75 It also determined that the

options were recurring regularly to the extent that the employee

could “expect to receive the executive stock options so long as he

continue[d] to work,”76 and that the options in question were

unexercised but fully vested. Under those facts and in the context of the Ohio child support statute’s definition of gross income, the court of appeals found that the stock options were

granted to the employee as an integral part of his compensation

package and should be included in his gross income for the purpose of computing child support.77

73

In re Marriage of Miller, 915 P.2d 1314, 1318 (Colo. 1996).

716 N.E.2d 288 (Ohio Ct. App. 1999).

75 Id. at 294.

76 Id. Under the Procter & Gamble Stock Option Plan in Murray, the

options were fully vested to the employee twelve months after the grant.

77 The Ohio Court of Appeals in Murray addressed the valuation of a

stock option. The court observed that “valuing stock options is difficult by nature” and that “the true value of the stock option to its owner is the potential

for appreciation in stock price without investment risk.” Therefore, it found

that to value the stock option simply using the stock price (i.e., market price) on

one day and comparing it to the exercise or strike price did not “accurately

reflect the value of the stock options.” Id. at 297, 298.

74

�\\Server03\productn\M\MAT\17-2\MAT207.txt

Vol. 17, 2001

unknown

Seq: 27

27-SEP-02

Stock Options

13:44

301

Whether an unexercised stock option will be considered income is relevant principally from two perspectives. First, is the

unexercised stock option a form of compensation that should be

included in the determination of the payor’s total compensation

for the purposes of the payment of alimony or child support?

Second, whether stock options that may vest or be granted subsequent to the termination of the marriage are assets which the

employee spouse will acquire as a result of efforts beyond the

date of termination of the marriage and, therefore, should be excluded from equitable distribution; or income which should be

considered in determining child support and alimony.78

To illustrate the issue, consider the following alternative

scenarios:

Family A - The employee spouse regularly received stock options

through her employment. On a regular basis, the stock options would

be exercised as they vested, the acquired stock would be sold and the

proceeds from the sale would be used to pay the parties’ ordinary and

recurring living expenses.

Family B - The stock options granted to the employee spouse

were treated the same as in Family A. However, the proceeds received from the sale of the stock were not used to pay recurring living

expenses but instead were applied directly and exclusively to the payment of their children’s college education expenses.

Family C – Similar to Family A and B, the employee spouse regularly received stock options. However, as the options vested, the family would make a decision whether they should retain the option or

exercise option and acquire company stock. If they felt that it was

economically prudent to not exercise the option, they would retain it

for future use. If they did exercise the option, they kept or reinvested

the acquired stock. They did not use any of the proceeds from the

exercise of the option or sale of the acquired stock for the payment of

any expenses and, instead, accumulated them for “a rainy day.”

Applying the analytical statistics cited at the beginning of

this paper, if the employee spouse in each of the three hypotheti78 This article will not discuss the issue that would arise if the amount or

value of the stock options received in years subsequent to the marriage exceeds

the value of the stock options which may have been received (and utilized by

the parties) during the marriage. As a general premise, if such stock options

are considered income, the increase in the employee spouse’s income for years

subsequent to the date of the marriage as compared to the years during the

marriage would entitle the children to benefit from such increase but would not

be considered with regard to spousal support or alimony which would be defined in the context of the standard of living during the marriage.

�\\Server03\productn\M\MAT\17-2\MAT207.txt

unknown

Seq: 28

27-SEP-02

13:44

302 Journal of the American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers

cal families had a total “compensation package,” including cash

and salary, stock awards and stock option awards of $500,000,

approximately 20% of that total compensation or $100,000 would

be paid in cash or salary and the remaining $400,000 would be in

short-term or long-term incentives such as stock programs or

stock option awards.

In Family A, the family’s standard of living would clearly

have been established and was dependent upon utilizing the full

$500,000.

In Family C, the family’s standard of living would have been

established and maintained utilizing only $100,000 while the remaining $400,000 was systematically accumulated as savings (i.e.,

assets).

Family B split the difference, maintaining their regular and

recurring expense budget at the $100,000 level, but paying extraordinary and temporary expenses (e.g., their children’s college

expenses, which would have a finite life span) out of the additional $400,000 income, presumably accumulating the remaining

balance of the $400,000 (i.e., assets).

Should the unvested future stock options in each of these

three families be treated the same? Did the parties themselves

treat them the same? Again, no definitive answer can be extracted from the case law. Thus, in attempting to answer the inquiry, guidance must come from logic and extrapolation of

principles gleaned from the holdings in other matrimonial cases.

Such an analysis would seem to indicate that the determination may turn upon the pattern that the parties’ established during the marriage, the standard of living established during the

marriage, and/or whether it was supported in whole or in part by

the stock options. If the statistic that approx