In re Seagate Technology, LLC - Impact

On (Potential) Accused Infringers, Their

Attorneys, and Patentees

By Robert H. Resis of Banner & Witcoff, Ltd.

Robert Resis has over 20 years of experience in representing clients in a wide variety of

intellectual property matters. His primary concentration is in trial work. Mr. Resis

practices in the Chicago office of Banner & Witcoff, Ltd., where he has spent his entire

legal career.

The en banc decision of the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals in In re Seagate

Technology, LLC, (Fed. Cir., August 20, 2007), overrules the Court's long time standard

for evaluating willful infringement as set forth in Underwater Devices Inc. v. MorrisonKnudsen Co., 717 F.2d 1380, 1389-90 (Fed. Cir. 1983). In Underwater Devices, the

Federal Circuit held that where “a potential infringer has actual notice of another's patent

rights, he has an affirmative duty to exercise due care to determine whether or not he is

infringing” and that such “an affirmative duty includes, inter alia, the duty to seek and

obtain competent legal advice from counsel before the initiation of any possible

infringing activity.”

In Seagate, the Federal Circuit held that “proof of willful infringement permitting

enhanced damages requires at least a showing of objective recklessness [and not a

negligence threshold associated with the duty of care announced in Underwater

Devices].” The Federal Circuit reemphasized that because it was abandoning the

affirmative duty of care, “there is no affirmative obligation to obtain opinion of counsel.”

The Federal Circuit went on hold that “to establish willful infringement, a patentee must

show by clear and convincing evidence that the infringer acted despite an objectively

high likelihood that its actions constituted infringement of a valid patent” and that the

“state of mind of the accused infringer is not relevant to this objective inquiry.” The

Federal Circuit further stated that “[i]f this threshold objective standard is satisfied, the

patentee must also demonstrate that this objectively-defined risk (determined by the

record developed in the infringement proceeding) was either known or so obvious that it

should have been known to the accused infringer.” The Federal Circuit stated that it

would “leave it to future cases to further develop the application of this standard.”

In light of its new willfulness standard, the Federal Circuit held “that the significantly

different functions of trial counsel and opinion counsel advise against extending waiver

to trial counsel. . . . Therefore, fairness counsels against disclosing trial counsel's

�communications on an entire subject matter in response to an accused infringer's reliance

on opinion counsel's opinion to refute a willfulness allegation.” The Federal Circuit noted

that “a willfulness claim asserted in the original complaint must necessarily be grounded

exclusively in the accused infringer's pre-filing conduct.”

By contrast, the Federal Circuit noted that “when an accused infringer's post-filing

conduct is reckless, a patentee can move for a preliminary injunction, which generally

provides an adequate remedy for combating post-filing willful infringement.” Indeed, the

Federal Circuit stated that “[a] patentee who does not attempt to stop an accused

infringer's activities in this manner should not be allowed to accrue enhanced damages

based solely on the infringer's post-filing conduct” and similarly, “if a patentee attempts

to secure injunctive relief but fails, it is likely the infringement did not rise to the level of

recklessness.” Thus, a “substantial question about invalidity or infringement is likely

sufficient not only to avoid a preliminary injunction, but also a charge of willfulness

based on post-filing conduct.”

The Federal Circuit stated that “[b]ecause willful infringement in the main must find its

basis in prelitigation conduct, communications of trial counsel have little, if any,

relevance warranting their disclosure, and this further supports generally shielding trial

counsel from the waiver stemming from an advice of counsel defense to willfulness. . . .

In sum, we hold, as a general proposition, that asserting the advice of counsel defense and

disclosing opinions of opinion counsel do not constitute waiver of the attorney-client

privilege for communications with trial counsel. . . . [As to work product protection],

“Again we are here confronted with whether this waiver extends to trial counsel's work

product. We hold that it does not, absent exceptional circumstances.” The Federal Circuit

held that “as a general proposition, relying on opinion counsel's work product does not

waive work product immunity with respect to trial counsel” and that “work product

protection remains available to ‘nontangible’ work product under [the Supreme Court’s

seminal case] Hickman.”

Impact on (Potential) Accused Infringers

Under Seagate, the willfulness inquiry is now whether an accused infringer acted as an

objectively reasonable entity would have acted under a totality of the circumstances. The

Seagate decision does not hold that relying on an opinion of counsel is irrelevant to that

inquiry. Thus, the Seagate decision should not be interpreted as a reason to stop seeking

opinions of counsel with respect to the patent rights of others. As well, companies need to

recognize that their conduct will be judged by their shareholders at a minimum.

Irrespective of the potential for treble damages based on a finding of willfulness,

shareholders will want management to reasonably review patent issues and take a prudent

approach before the company engages in significant commercial investments and efforts

relating to proposed goods and services. Indeed, in some cases, infringement can be

avoided based on some basic knowledge of the issues.

Where the Seagate decision may have the most significant impact is in instances where

there are or will be dozens or more components used in a product or way of doing

business, and possibly hundreds or more patents on some or all of the components and/or

�various combinations thereof. These instances frequently arise in the electronics and

telecommunications industries. Under Seagate, an entity that contemplates a new product

and/or service no longer has a “duty to seek and obtain competent legal advice from

counsel” as to every one of such patents “before the initiation of any possible infringing

activity.”

An entity that contemplates a proposed product or service may still want to take a

conservative approach by identifying what appear to be the most relevant patent(s) and

satisfy itself that there is no “objectively high likelihood that its actions [will constitute]

infringement of a valid patent" so identified. To do so, the entity may decide to do a

design around and/or obtain competent legal advice from counsel as to a patent(s)

identified as being the most relevant. An entity may consider doing the same exercise to

the extent not already done when it receives notice of a particular patent from a patentee

and has been threatened with an infringement suit regarding a proposed or existing

product or service.

When an entity decides to obtain opinion advice from counsel regarding a patent and its

proposed or actual activities, it should ensure that the opinion advice is rendered by

counsel other than who the entity wants to have as trial counsel. If opinion counsel and

trial counsel are the same attorney, then the holding of Seagate would not be applicable

and the patentee could then obtain all opinions of trial counsel because he or she would

be the same individual as opinion counsel. In an abundance of caution, the entity may

want to engage outside counsel from one law firm to provide opinion advice and another

law firm to be trial counsel.

Because the Seagate decision appears to make it more difficult for a patentee to prove by

clear and convincing evidence that an infringer’s infringement was willful, an entity that

is negotiating a license or settlement with a patentee will be in a better bargaining

position even if that entity did not have a opinion of counsel before the filing of a lawsuit.

Impact on the Attorneys of (Potential) Accused

Infringers

Attorneys who represent potential accused infringers or accused infringers should ensure

that their clients understand the change in the law under the Seagate decision so that their

clients do not have any misconceptions based on past law or experiences. Still, attorneys

should make clear to clients that the law will continue to evolve, particularly since the

Federal Circuit has left “it to future cases to further develop the application of [its new]

standard.”

Law firms that wish to be both opinion counsel and trial counsel should ensure that the

attorney(s) providing the opinion advice are different from the attorney(s) acting as trial

counsel.

Impact on Patentees

The Seagate decision appears to make it more difficult for a patentee to prove willfulness

�by clear and convincing evidence since there is no longer a “duty of care”. Further, a

patentee who does not obtain a preliminary injunction should not expect enhanced

damages based on post-filing infringement. Thus, a patentee should have lower

expectations of recovery from an accused infringer in negotiations and at trial.

Do not be surprised, however, to see a patentee argue that the fact an accused infringer

obtained an opinion of counsel is admissible evidence that the accused infringer knew of

the “objectively-defined risk,” thereby satisfying the second part of the new test of

willfulness under Seagate. This argument would seem to be persuasive in only certain

circumstances, such as where there is chicanery behind the opinion.

Conclusion

Since the Federal Circuit stated it was leaving it to future cases "to further develop the

application" of the recklessness standard, uncertainty exists as to how the application of

the standard will develop in the future. In the meantime, a (potential) accused infringer

will need to navigate a path to best show that it did not have an objectively high

likelihood that its actions constituted infringement of a valid patent. Accused infringers,

potential accused infringers, and their attorneys should ensure clear distinction between

opinion attorney(s) and trial counsel. Patentees should have lower expectations of

proving willfulness, and corresponding settlements and recoveries.

�

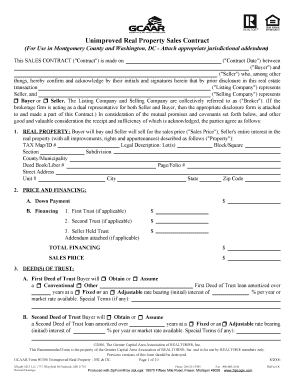

Useful advice on preparing your ‘Unimproved Real Property Sales Contract’ online

Are you weary of the difficulties associated with handling paperwork? Look no further than airSlate SignNow, the premier electronic signature platform for individuals and small to medium-sized businesses. Bid farewell to the tedious process of printing and scanning documents. With airSlate SignNow, you can easily complete and sign paperwork online. Utilize the powerful tools integrated into this straightforward and affordable platform to transform your document management approach. Whether you need to approve forms or gather electronic signatures, airSlate SignNow manages it all simply, with just a few clicks.

Follow this comprehensive guide:

- Log in to your account or initiate a free trial with our service.

- Click +Create to upload a file from your device, cloud storage, or our template library.

- Open your ‘Unimproved Real Property Sales Contract’ in the editor.

- Click Me (Fill Out Now) to finalize the document on your end.

- Add and assign fillable fields for others (if necessary).

- Proceed with the Send Invite settings to solicit eSignatures from others.

- Download, print your copy, or convert it into a reusable template.

No need to worry if you have to collaborate with others on your Unimproved Real Property Sales Contract or send it for notarization—our platform has everything you need to accomplish these tasks. Sign up with airSlate SignNow today and elevate your document management to a new standard!