Vol. 11, 1355 – 1357, February 15, 2005

Clinical Cancer Research 1355

The Biology Behind

Nucleotide Excision Repair, Oxidative Damage, DNA Sequence

Polymorphisms, and Cancer Treatment

&& Commentary on Gu et al., p. 1408

Stephanie Q. Hutsell and Aziz Sancar

Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, University of North

Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, North Carolina

INTRODUCTION

Can a single polymorphic site help tailor a cancer patient’s

chemotherapy regimen? The study by Zhao et al. (1) presented in

this issue of Clinical Cancer Research suggests that in fact

polymorphic sites in noncoding gene regions may determine how

a patient will react to a given chemotherapy and the likelihood of

cancer recurrence after treatment. The group focused their

investigation on a common polymorphism termed xeroderma

pigmentosum group A ( 4) [XPA ( 4)], whereby the fourth

nucleotide before the ATG start codon is A in about half the

population and G in about the other half (2, 3). The polymorphism

is in the Kozak sequence and thus the A form of the allele may

affect the translation efficiency of XPA resulting in reduced XPA

level and reduced excision repair capacity. Indeed, this group

previously reported that the A allele (XPA A variant in the authors’

terminology) is associated with reduced excision repair capacity

(4). In the current study, the authors report that the XPA G variant

in which both alleles contain G at the fourth position before the

initiation codon is associated with a higher rate of recurrence of

superficial bladder cancer after Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG)

treatment. The authors report that during the follow-up period of

27.6 months from diagnosis, tumor recurred in 44% of patients

with the AA genotype, 62% in those with the AG genotype, and

74% in those with the GG genotype. To explain these findings, the

authors suggest that the XPA G variant exhibits increased DNA

repair capacity by nucleotide excision repair. This allows cancer

cells to bypass the apoptotic response induced by BCG treatment.

Nucleotide excision repair is the only human system that

protects against the carcinogenic effects of sunlight by removing

UV light-induced DNA adducts such as (6 – 4) photoproducts

and cyclobutane thymine dimers (5 – 8). Along with lightinduced lesions, the excision nuclease recognizes and excises a

broad spectrum of bulky lesions such as benzo(a)pyrene,

acetylaminofluorene, cisplatin, and psoralen DNA adducts (5).

The mechanism of excision repair is highly conserved from

E. coli to man and involves a damage recognition step, dual

incisions bracketing the lesion, removal of the damage in the form

of a 12- to 13-nucleotide-long oligomer in E. coli and a 24- to 32-

Received 1/6/05; accepted 1/13/05.

Requests for reprints: Aziz Sancar, Department of Biochemistry and

Biophysics, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Mary Ellen

Jones Building, Campus Box #7260, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7260. Phone:

919-962-0115; Fax: 919-966-2852; E-mail: Aziz_Sancar@med.unc.edu.

D2005 American Association for Cancer Research.

nucleotide-long oligomer in humans, repair synthesis to fill the

resulting gap, and finally ligation of the repair patch.

Human nucleotide excision repair has been recently

characterized at the biochemical level in considerable detail.

Six repair factors, XPA, RPA, XPC, TFIIH, XPG, and XPFERCC1, are necessary and sufficient to remove damage from

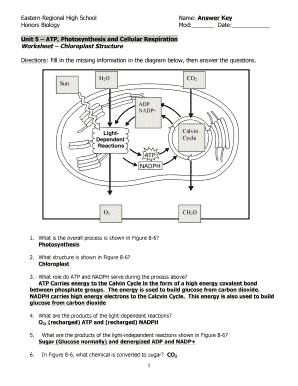

DNA. A current model for human nucleotide excision repair is as

follows: XPA, RPA, and XPC locate the damage site and recruit

the TFIIH transcription/repair factor, which contains six polypeptides including helicases XPB and XPD that unwind the DNA

around the damage site; the XPG and XPF-ERCC1 subunits are

responsible for the 3V and 5V dual incisions, respectively. Repair

synthesis proteins replication factor C, proliferating cell nuclear

antigen, and DNA polymerases y and q fill the gap, and in the

final step, the repair patch is sealed by DNA ligase I (refs. 9, 10;

Fig. 1). Mutations in any of the XP A-to-G coding sequences

result in XP, a disease characterized by extreme light sensitivity

and high incidence of skin cancer. Currently, all known XP cases

contain mutations in the coding regions of one of the XP genes. It

is conceivable that mutations in the noncoding or nontranscribed

regions of the XP genes may cause slight alteration in gene

expression so as not to give rise to an overt XP phenotype, but

of significant magnitude that subtle repair defects may manifest.

Even though nucleotide excision repair is generally thought

of as a repair system for bulky adducts, it has been shown that

it works with moderate efficiency on nonbulky DNA lesions,

such as DNA bases altered by oxidative damage that are usually

processed by base excision repair (11, 12). Because of this

property, the nucleotide excision repair system plays a backup

role for the base excision repair pathway in the removal of such

DNA adducts. Reactive oxygen species are by-products of

oxidative metabolism and are also produced in great quantities

during inflammatory reactions. They induce numerous DNA

lesions including thymine glycols, 8-oxoguanine, and cyclodeoxyadenosine. Nucleotide excision repair is capable of

removing all of these DNA lesions induced by reactive oxygen

species (13, 14).

In the study by Zhao et al. (1), the authors propose

a mechanism that involves the nucleotide excision repair pathway

and its response to oxidative damage, to explain why the XPA G

variant is less responsive to BCG treatment. The suggestion is

that BCG therapy provokes an inflammatory cellular response,

which subsequently results in the production of oxygen radicals

and extensive oxidative damage to DNA followed by apoptosis.

The XPA G variant was reported to have increased DNA repair

capacity (4). This increase in DNA repair capacity may be

responsible for removing a greater percentage of oxidative

damage from DNA, preventing the apoptotic pathway, and

permitting tumor cell survival, rendering BCG ineffective for

patients homozygous for the XPA G variant.

Downloaded from clincancerres.aacrjournals.org on July 11, 2018. © 2005 American Association for Cancer

Research.

�1356 Nucleotide Excision Repair Gene

Fig. 1 Model for nucleotide excision repair.

Damage is recognized by RPA, XPA, and XPC in

a cooperative way. TFIIH is recruited to form preincision complex 1 (PIC1). XPG displaces XPC

from PIC1 to form PIC2. Finally, XPF-ERCC1 is

recruited to form PIC3 in which XPG makes the 3V

incision 6 F 3 nucleotides 3V from the damage site

and XPF-ERCC1 makes the 5V incision 20 F 5

nucleotides 5V to the damaged bases releasing the

damage in the form of a 27-nucleotide-long

oligomer. Repair synthesis proteins replication

factor C, proliferating cell nuclear antigen, and

DNA polymerases y and q fill the gap. Repair patch

is sealed by DNA ligase.

This is a reasonable speculation. However, there are certain

caveats to this interpretation. The report that the XPA G variant

allele shows increased DNA repair capacity requires verification

by more than just the reporter gene assays reported previously (4).

Currently, there is no evidence that the level of XPA protein is

increased constitutively or in response to damage in XPA G variant

patients. Furthermore, there is no evidence by independent repair

assays that there is increased excision repair activity in cells with

the XPA G variant. In addition, although it has been shown that

human nucleotide excision repair excises 8-oxoguanine, thymine

glycol, and perhaps other oxidative stress base lesions from DNA

as efficiently as the light-induced cyclobutane thymine dimer

(13), 8-oxoguanine and other oxidative stress lesions are repaired

very efficiently by 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase and other

glycosylases (15). Therefore, the magnitude of contribution of

nucleotide excision repair in the removal of oxidative damage to

nucleotide bases remains to be determined. As a final caveat,

previous studies (4, 16) have shown that the XPA G variant allele

has a protective effect against the onset of lung cancer. Those

reports predict that individuals with XPA G variant would have

lower incidence of bladder cancer as well. Zhao et al. (1) did not

study an unaffected sample of the population to determine if the

XPA G variant allele shows a similar protective effect against

superficial bladder cancer. If it does, this study reveals an

interesting issue in the genetic consideration in carcinogenesis and

cancer treatment: a mutation makes the carriers more resistant to

cancer, but once they develop cancer, the same mutation may

make them less responsive to treatment by agents that directly or

indirectly damage DNA.

This is an interesting study, and in conclusion, the

connection between the XPA G variant polymorphism and lack

of response to BCG treatment could have significant clinical

Downloaded from clincancerres.aacrjournals.org on July 11, 2018. © 2005 American Association for Cancer

Research.

�Clinical Cancer Research 1357

applications. However, whether or not this polymorphism

is relevant to nucleotide excision repair activity needs further

investigation.

REFERENCES

1. Gu J, Dinney CP, Zhu Y, et al. Nucleotide excision repair gene

polymorphisms and recurrence after treatment for superficial bladder

cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;11:1408-16.

2. Richards FM, Goudie DR, Cooper WN, et al. Mapping the multiple

self-healing squamous epithelioma (MSSE) gene and investigation of

xeroderma pigmentosum group A (XPA) and PATCHED (PTCH) as

candidate genes. Hum Genet 1997;101:317 – 22.

3. Butkiewicz D, Rusin M, Harris CC, Chorazy M. Identification of four

single nucleotide polymorphisms in DNA repair genes: XPA and XPB

(ERCC3) in Polish population. Hum Mutat 2000;15:577 – 8.

4. Wu X, Zhao H, Wei Q, et al. XPA polymorphism associated with

reduced lung cancer risk and a modulating effect on nucleotide excision

repair capacity. Carcinogenesis 2003;24:505 – 9.

5. Sancar A. DNA excision repair. Annu Rev Biochem 1996;65:43 – 81.

6. Sancar A, Lindsey-Boltz LA, Unsal-Kacmaz K, Linn S. Molecular

mechanisms of mammalian DNA repair and the DNA damage

checkpoints. Annu Rev Biochem 2004;73:39 – 85.

7. Wood R. Nucleotide excision repair in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem

1997;272:23465 – 8.

8. Sancar A, Reardon JT. Nucleotide excision repair in E. coli and man.

Adv Protein Chem 2004:69:43 – 71.

9. Mu D, Hsu DS, Sancar A. Reaction mechanism of human DNA repair

excision nuclease. J Biol Chem 1996;5:8285 – 94.

10. Reardon JT, Sancar A. Recognition and repair of the cyclobutane

thymine dimer, a major cause of skin cancers, by the human excision

nuclease. Genes Dev 2003;17:2539 – 51.

11. Branum ME, Reardon JT, Sancar A. DNA repair excision nuclease

attacks undamaged DNA. A potential source of spontaneous mutations.

J Biol Chem 2001;6:25421 – 6.

12. Huang JC, Hsu DS Kazantsev A, Sancar A. Substrate spectrum of

human excinuclease: repair of abasic sites, methylated bases, mismatches,

and bulky adducts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1994;91:12213 – 7.

13. Reardon JT, Bessho T, Kung HC, et al. In vitro repair of oxidative

DNA damage by human nucleotide excision repair system: possible

explanation for neurodegeneration in xeroderma pigmentosum patients.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997;19:9463 – 8.

14. Kuraoka I, Bender C, Romieu A, et al. Removal of oxygen freeradical-induced 5V,8-purine cyclodeoxynucleosides from DNA by the

nucleotide excision-repair pathway in human cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci

U S A 2000;11:3832 – 7.

15. Fromme JC, Verdine GL. Base excision repair. Adv Protein Chem

2004;69:1 – 41.

16. Butkiewicz D, Popanda O, Risch A, et al. Association between the

risk for lung adenocarcinoma and a ( 4) G-to-A polymorphism in the

XPA gene. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2004;13:2242 – 6.

Downloaded from clincancerres.aacrjournals.org on July 11, 2018. © 2005 American Association for Cancer

Research.

�Nucleotide Excision Repair, Oxidative Damage, DNA

Sequence Polymorphisms, and Cancer Treatment

Stephanie Q. Hutsell and Aziz Sancar

Clin Cancer Res 2005;11:1355-1357.

Updated version

Cited articles

Citing articles

E-mail alerts

Reprints and

Subscriptions

Permissions

Access the most recent version of this article at:

http://clincancerres.aacrjournals.org/content/11/4/1355

This article cites 12 articles, 4 of which you can access for free at:

http://clincancerres.aacrjournals.org/content/11/4/1355.full#ref-list-1

This article has been cited by 1 HighWire-hosted articles. Access the articles at:

http://clincancerres.aacrjournals.org/content/11/4/1355.full#related-urls

Sign up to receive free email-alerts related to this article or journal.

To order reprints of this article or to subscribe to the journal, contact the AACR Publications

Department at pubs@aacr.org.

To request permission to re-use all or part of this article, use this link

http://clincancerres.aacrjournals.org/content/11/4/1355.

Click on "Request Permissions" which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center's

(CCC)

Rightslink site.

Downloaded from clincancerres.aacrjournals.org on July 11, 2018. © 2005 American Association for Cancer

Research.

�