Streamline your research and development process with pipeline integrity data for R&D

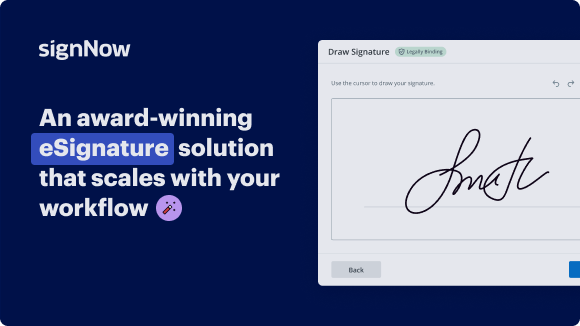

See airSlate SignNow eSignatures in action

Our user reviews speak for themselves

Why choose airSlate SignNow

-

Free 7-day trial. Choose the plan you need and try it risk-free.

-

Honest pricing for full-featured plans. airSlate SignNow offers subscription plans with no overages or hidden fees at renewal.

-

Enterprise-grade security. airSlate SignNow helps you comply with global security standards.

Pipeline integrity data for R&D

Pipeline integrity data for R&D

airSlate SignNow not only ensures the security and legality of your documents but also simplifies the entire signing process for you and your recipients. Get started with airSlate SignNow today and experience the convenience of managing pipeline integrity data for your R&D projects efficiently.

Try airSlate SignNow by airSlate now and take your pipeline integrity data for R&D to the next level!

airSlate SignNow features that users love

Get legally-binding signatures now!

FAQs online signature

-

What is pipeline integrity?

in its purest form the term “pipeline integrity” refers to a comprehensive program that ensures. hazardous commodities are not inadvertently released from a pipeline and minimizes the impact. if a release does occur.

-

What are R&D pipelines?

The Basics. What: The pharmaceutical research & development (R&D) pipeline is the process for identifying a potentially beneficial drug, proving that it is safe and effective, and making it available in a way that maximizes its benefit to as many patients as possible.

-

What is the R&D pipeline?

The Basics. What: The pharmaceutical research & development (R&D) pipeline is the process for identifying a potentially beneficial drug, proving that it is safe and effective, and making it available in a way that maximizes its benefit to as many patients as possible.

-

What are the phases of drug discovery pipeline?

To be deemed a “success,” a new drug must make it through five specific phases: 1) discovery and development, 2) preclinical research, 3) clinical research, 4) FDA review, and 5) safety monitoring. Below, we explore each step in more detail.

-

How do you ensure data quality in data pipeline?

Example Data Pipeline: Uniqueness and deduplication checks: Identify and remove duplicate records. ... Validity checks: Validate values for domains, ranges, or allowable values. Data security: Ensure that sensitive data is properly encrypted and protected.

-

What are the stages of research development?

The research method uses Research and Development (R&D) has 7 stages: (1) the potential and problem analysis stage, (2) the data collection stage, (3) the product design stage, (4) the product validation stage, (5) the product revision stage, (6) product trial phase, (7) data analysis and reporting stages.

-

What are the stages of R&D development?

The R&D phases of these projects can vary considerably from company to company and industry to industry, but there are a few phases applicable to all R&D projects – strategy and planning, research, development, testing, and launch. Before you start an R&D project, the company needs to align on an R&D strategy.

-

What are the stages of the R&D pipeline?

The R&D pipeline involves various phases that can broadly be grouped in 4 stages: discovery, pre-clinical, clinical trials and marketing (or post-approval). Pharmaceutical companies usually have a number of compounds in their pipelines at any given time.

Trusted e-signature solution — what our customers are saying

How to create outlook signature

For those of you who don't know me, my name is Meghan Harris. I am a data scientist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. And I'm here today because I have a story to tell you all about data pipelines and R. But before I get into that, I do have a quick question for all of you. You don't have to answer me out loud, but when you see this image, does it make you feel anything or have any ideas on what it is? Well, this is my personal 100% accurate representation of a data pipeline, and now you're all thinking I'm out of my mind, and I might be, but hear me out. Of course, this isn't an actual data pipeline, right? But rather the mental images and feelings I had when I was tasked with making a data pipeline from scratch in my last position as a data specialist. The story I want to tell you all today is about how I created that pipeline in R within the context of me being a self-taught, programmer. Those of us that work in data, when we think of data pipelines, I sure as hell hope it does not look like that. But hopefully it looks maybe something more like this. A perfect data pipeline, clean processes, clean structures, great results. This is a pipeline to most of us, but in the last position I was in, the pipeline looked nothing like that at all. If we could even say there was a pipeline, it was very clunky. No structure, no automation, just bad vibes and recklessness. So, although I have learned a lot and I have so much to share, I don't have a lot of time to talk. Y'all we'll be lucky if we get under 19 minutes, I'm going to be honest. So I pulled out four main points that I learned about creating pipelines during this journey. These are going to touch on my first encounters within the data and the pipeline, the importance of identifying the environmental structures of the pipeline, embedding validations within the pipeline, and understanding what sustainability looks like for the pipeline. Now keep in mind that all of these main points could easily be their own talks, their own lectures, their own courses. So I'll only touch on the biggest takeaways. However, I have created a list of example pipeline scripts, actual Shell template documents that you guys can all use that is in the repo for this talk on GitHub. Yes, I know. Great right. So with that out of the way, I think the best thing for me to do is go back to the beginning during those first encounters I had with this pipeline. And guys I know I'm going to sound really out of my mind again, but the very first thing I learned about making data pipelines in R was to not open R. Ah, now I know you're thinking Megan we're at RStudio conf, what are you talking about? I know, but hear me out. Let me give you some context. This was me on my first day as a data specialist, my first professional data position. I am self-taught so I'm already coming in. Not familiar with things, but I'm also not familiar with the subject matter. This physician was dealing with opioid data. There was a lot of data existing everywhere and the organization I was working directly with did not have any structure in place, nor did they have any expectations about what I was to do. So if I am a new self-taught programmer newbie and I'm coming in with no direction, what did I do? So just like this dude is jumping head first to get to the Winchester, shout out to Shaun of the Dead. I also dove in headfirst into RStudio as soon as I got any data, and that's what I did. Whenever I got a new data set, I tried to create R programs immediately and what I should have done was actually started investigating. I didn't ask basic questions. I didn't ask for code books, I didn't try to validate anything. It was just recklessness and vibes, I told you guys. But I argue this point of not opening RStudio with an example of something that happens to me that was traumatic. I call it the Narcan story. Now, for those of you who don't know, Narcan is a medication that is used to reverse opioid overdoses. So, of course, working with this type of data, I'm going to see this information at some point. One day I get a data set and there is a variable in it called Narcan. And like I did, opened up RStudio, quickly, looked at it and saw, oh, Narcan has numbers in it, OK numbers. So without doing anything else, I immediately start making automated reports, dashboards. I'm feeling like I am a freakin' superwoman, man. I'm awesome. And, you know, I just I woke up in the middle of the night, like, months after that, and I had just a random just Eureka moment, kind of felt like something was wrong. I woke up and I was like, HMM, something ain't right, chief. What is it? So I went to RStudio, I opened it up and I saw a value and it was 4 plus. And guys, my heart sunk because 4 plus is not a number. 4 plus is a string. So four months I was calculating off of this variable that I did not even know how, but I was coercing a character variable into an numeric variable. So imagine the embarrassment of going back after everyone's relying on me for this and being like, hey guys, it's wrong. So that was just one example of many times that happened to me. All right. And clearly, you can see here, I learned a lot, but the main thing I learned was to not jump into RStudio as soon as you get a data set. If you do want to jump in it, only use it to give you a little bit of context, a little bit of clues so that you can ask more information. It was a really hard lesson that I had to learn, to just go through this iterative process of asking questions, but doing so gave me just a little bit more clarity. So remember how that pipeline looked like in my head when I dove in headfirst with no information? Well, now that I had an investigation, it looks still messy. It looks messy, and it doesn't seem like much change. But I guarantee you this is a different picture. But just enough started to clear up. So that I could accept that fact that I needed to start building on this. I needed to make some structure. So at this point, we're going to try to add some environmental structure, right? So the biggest thing I learned about environmental structures is that theta pipelines can actually exist in two types of environments, something that I'm terming as external and internal environments. Now, there's probably way more sophisticated ways to think about this and break this down. But I'm a beginner and this is what my beginner brain like made sense. This is what made sense. So when starting out, I had realized they had external things outside of my computer that was affecting the data inside of my computer, but also things inside of my computer, inside of RStudio that was affecting it as well. And I'll explain both of them. So when I say external environment, I'm talking about more abstract concepts. I'm talking about any kind of data, interactions, decisions, admin policies that can affect the flow of the data. Even the technology that's used for data collection and even the data literacy of whoever you are working with. It was so important to identify all of these concepts because at some point, they are going to affect your internal flow of your pipeline. It's going to affect how you end up working with and structuring your data internally. Now, the internal environment is what most people think about when they hear the words data pipeline. They think about the actual file structures, the flow of things happening internally, the logic of processing, and even the data security and storage methods. Now, it should go without saying that this isn't the reality, right? We don't have two separate environments that exist in silos. There's external things that affect internal things and vice versa. And this is a challenge that most every data person knows well. Even if we don't think about environments in this way, I'm sure that if any of you work in nonprofit or academia or government or anywhere, you probably have some form of bureaucracy affecting what you do, maybe even conflicting interests in decisions. That's an example of this. So what helps me to better navigate the interactions between these two environments was to repeatedly tackle each environment by introducing some structure, some documentation for one, and adjusting for the other. So I just want to give a really quick. A sample of just some documents that I made to try to help me out with this. So when I was thinking about structuring my external environment, you guys got to remember I was a one person data team. Really, I was the only person coding an R, so everyone else that I was working with had no concept of this, did not do any coding, whatever. So my method of trying to introduce some structure was to get everybody on the same page. So for this example, I have up here making metadata and very loosely metadata is literally just data about data. What helped everybody else around me to kind of help me with what they wanted was to make sure that they understood what was happening. So what was the name of the file like for the data? How often was it collected? How was it collected? Those simple things we don't think about, it really helps to have it documents it somewhere. Another example, I have is something that I'm terming as assess, attempt, repeat. We all do this. How many of you have gone to a new organisation? Saw the way that they were doing something and was like, HMM, this ain't right. So you get in, you assess your situation and you attempt to make a change. Now, if we're lucky, it's the attempt is successful and it's great. And what usually happens is that we either have people who have been there that's just like we're not doing that or something just doesn't work. So when I tried to do this, I would try to make the change outside externally, maybe in a way that we collect data or anything. But nine times out of 10 I ended up having to compromise and make up for it internally in my systems. So speaking of internally, there's also some examples of introducing some structure this way. So the first example, I have here is simply named "make clean file structures". And this is so much more than like, oh, making sure your folder names are clean and making sure your data is in a data folder. Your scripts are in a script folder. This also encompasses knowing how to work with R project files. This encompasses knowing where you are in your working directory, knowing knowledge about working directories, because that's the only way that you are going to get a full flow automation process with everything stored organized in a good way and seamless. And like I said, if you need to more about working directories or R project files or anything, Jenny Bryan and all of the amazing people have already made resources for it, especially with the here package and that is linked on my repo. I'm not going to act like I know about that too much. The next example, I have is something that I'm terming as modlarizing your code. Now, in this example, it's being modularized by data and component. So this is a snip from an actual large project I had where I had so many data sources, right? So it made sense for me to do the work for each data source within one script. Now, that's only one way to do it. You know, that's it might work for you and it might not, you know. But another example that you can also do is modularizing your code by function or by process. And I usually do this when I don't have too many data sources and I have a more manageable project. Now in this example, I'm showing three scripts in my working directory here. I have a docking script, which I'll explain that in the next slide. I have a processing script which is just for doing transformations and cleaning, and I have a visualization script or this script for short, which is literally just making vizzes, right? So what helped me with these projects was having individual scripts that I could call on when it was time to use it in the pipeline. So the last example, I have here for structuring internal environments is something that I'm calling connecting and chaining where it makes sense. And honestly, I could have just called it docking scripts. I don't know why I talk too much. So an example of a docking script is on these next few slides, and I want to stress the importance of the content in it is not so much important, but just the logic of what is happening is. Now, in my terms in my Megan brain, a docking script is one R script that will literally bring in your data, do your cleaning, your validation, do everything that it needs to do. So that when you hit that source button at the top, everything does what it needs to do. And your end result is hopefully a deliverable that you're looking for, whether it is a Shiny app or a clean data set. So just to get into it just a little bit, the docking script starts just like any other R script will start. We'll load in our libraries, then the next section will go into is something that I call the data process check here. Now this looks maybe hopefully not complicated, but this is literally just bringing in your data and then determining how you want to have some logic values. So if you want to do something to check like very simply down here, this last line, it's just checking a new data set against an old data set to see if the value of rows change. And I don't recommend doing that. I don't have time to get into why, but don't do it. But you'll get a logic value at the end of this section. So then the next section I have here is a logic flow for processing. So this is just very simple. If scripts, if statements. So if the data has updated, we will then tell R to source one of our modularized codes. We will tell R that OK, if there's new data, go ahead and process that data. If there's new data, go ahead and make a visualization for it. So that can look very complicated, obviously, depending on what you got going on in your project. But after all of that is done, you can embed options in your docking script to render your output. So in this case, it's a simple HTML report and an example of a working, hopefully working, version of this is on the repo, you can see. So now that I've zoomed by that and realize that, oh, I needed environmental structure, my data pipeline looks like this in my head. I still don't know what this is. And I'm really anal, so I hate that the lines are crooked like that. So what can I do to try to clear up the image of my mental data pipeline? Well, we can add data validations. And let me tell you guys, I am exposing myself here because you guys know what I learned about data validations. I learned that you have to do them because if you do not check yourself, you will indeed wreck yourself. You absolutely will. OK I'm going to be honest, I am not the person to stand up here talking about validations. I am still learning myself. But I can tell you that the most important thing that I learned was to do them. Because, man, I could have saved myself so much pain if I had just checked that damn variable. Man oh, my God. So what I can do is just give you some examples of some types of validations that I did run into. Now, I won't go into all of these specifically. This is kind of here just for a think piece. So if any of you are doing the same, you can reference, this and be like, HMM, do I have data that fits this as well? Now something that I did actually learn on my own is that validations can exist externally and internally. So in my case, or in my opinion, the best scenario has always been that validations are implemented externally, whether that's at the point of data collection or whatever. If it's external, if it's externally implemented, it might increase the chances of your data being actually like workable and clean by the time it gets to you internally. Hopefully it's less work, but my usual scenario has been that there's no validation done and that I have to do everything. And it feels like it's way more work than it needs to be. But that's just me, right? So OK, I realized I have to do validations. That's the thing. I did the manually in R and there's nothing wrong with that. But it can be cumbersome. But there's packages. Guys, I didn't know this shout out to Crystal Lewis because she told me about the pointblank package. I was late, like I literally learned about it two days ago. I had to change my slides. So this is here for both of us to, or for all of us, to learn together. So if you are also in the dark, like I was, we can learn together because I don't know about validations. You just got to do them guys. So, OK, now that we have determined that we needed data validation, this is what my pipeline looks like. Now I see some shapes, but I'm going to be honest with you guys. I still don't those lines, so what else can I add? So our last point is sustainability. So sustainability can mean and look like a lot of different things. And I'm going to be honest guys, because I was a one person data team. I did not have any bandwidth to do any type of real sustainability efforts but what I was able to do was kind of look at the work that I did to see, OK, what is really going to count for sustainability or what's going to help with this pipeline and what do I wish I could have done? So this is just a quick list of things that I brainstormed with, like, man, like if I had the time to do it, I wish I could. But the things that I did highlight and star here are things that I actually eventually did get to do before I had left that last position. And my point of putting this up here again is a think piece slide. So what I want all of you to take away from this part of the session is to kind of ask yourself, do you or your organization, wherever you're working with your data, do you guys have sustainability efforts in place or are you in a cyclic cycle of just reaching the next deadline? And if so, are there ways to start incorporating making some sustainability efforts to do some QA or QI on your pipelines? So the last thing I can share with you guys is just some really, really quick examples of things I tried to do to try to document, right? Because with me being a one person data team, the best thing I had to do was documents everything so that people that didn't code or didn't do data could understand what needed to happen, especially when I ended up resigning so that my work didn't just fall apart. So this is an example that I have fully on the repo as well, and this is a data workflow map. So what helped me was actually visualizing all the different data sources that I had going into one of my pipelines, literally explaining where it was coming from, but then visualizing what's happening inside of R for other people. Another example, I think this looks really similar to a SQL schema. I'm sorry I suck at SQL, so I don't know if that's true, but pretty much again, just a readable version so that people that wasn't working in data can look and say, OK, we have these data sets and these are the variables in it. And these are the possible ways we can relate them to one another. OK so now that I've zoomed by all of that, let's, let's recap. So this was my pipeline in my head before we did anything, when we just jumped in headfirst. This is what it looked like when we started to investigate that environment, ask questions about the data. This is what it looked like when we added some structure, when we realized data validation was a thing and when we tried to add some sustainability. And you know what? I still don't know what this is a picture of, but I know that it looks kind of pretty and that it has some clear shape, some straight lines and some colors. And maybe that's the point. Right? so if you are someone that's just starting out in data science or teaching yourself how to use R like I was, something that you may have learned is that having things just be functional can be just enough. And sometimes you may never even know everything about the data you're dealing with, but you can appreciate the beauty of the unknowns and the efforts that have been made to create the pipeline that you do have to work with. Of course, through time, you want to evolve and use best practices and feel that we're 100% knowledgeable on what we do. But my hope is that I've given you guys something useful to take back with you today to try to make this process of making data pipelines a little less painful, especially if you're going to do the same thing that I did and make them from scratch. in R, Thank you for listening, guys.

Show more