Extraterritoriality, Institutions, and Convergence in International Competition Policy

William E. Kovacic1

Introduction

Competition law is an increasingly common element of public economic policy. A halfcentury ago, one country (the United States) had antitrust statutes and active enforcement. Today

over 90 jurisdictions have competition laws, and the number will exceed 100 by the decade’s end.2

Many antitrust laws lack effective implementation, yet a growing number of jurisdictions have

enforcement mechanisms that business operators must take seriously.

The global expansion of competition law influences cross-border commerce. National or

regional antitrust systems frequently endorse the comparatively broad view of extraterritoriality

pioneered by the United States and the European Union (EU).3 This development ensures that

individual transactions or practices involving major suppliers of goods and services often will be

subject to scrutiny under the competition laws of more than one (often many) jurisdictions.

Despite important similarities, the world’s competition systems do not conform to a single

1

General Counsel, U.S. Federal Trade Commission. This paper is based upon a

presentation given at the Annual Meeting of the American Society of International Law in

Washington, D.C. on April 5, 2003. A revised version of the paper is published at 97 ASIL

Proc. 309 (2003). The views expressed here are the author’s alone and not necessarily those of

the Federal Trade Commission or any of its individual Commissioners.

2

These developments are examined in William E. Kovacic, Institutional

Foundations for Economic Legal Reform in Transition Economies: The Case of Competition

Policy and Antitrust Enforcement, 77 Chi-Kent L. Rev. 265 (2001) (hereinafter Institutional

Foundations).

3

On the evolution of the “effects” doctrine and its acceptance by various

competition policy regimes, see Edward T. Swaine, The Local Law of Global Antitrust, 43

William & Mary L. Rev. 627, 641-46 (2001).

1

�model. The multiplication of antitrust laws raises concerns that enforcement by jurisdictions with

dissimilar substantive standards, procedures, and capabilities will discourage legitimate business

transactions and needlessly increase the cost of controlling anticompetitive conduct.

Recognition of the problems associated with competition system multiplicity has inspired

measures to promote convergence toward international norms. My presentation focuses on the

development of institutions to promote consensus about the appropriate design of competition

policy.

I summarize trends in creating competition law regimes, identify issues involving

multiplicity and extraterritoriality, and discuss one initiative, the International Competition Network

(ICN), to create international institutions to promote the development and acceptance of common

norms.

The Modern Development of Competition Laws

As recently as 1970, a practitioner seeking to master international competition law would

have needed to study only the antitrust regimes of the United States, the European Union (EU), and

several EU member states. Enforcement in other jurisdictions with competition statutes was so weak

that business managers safely could ignore the laws.

The past three decades have featured a remarkable transformation. Older market economies

such as Australia and Canada have rejuvenated dormant antitrust systems. Competition law is a

frequent component of law reform in nations moving from planning to markets. Over 50 transition

economies have adopted antitrust laws since 1970.4 The effectiveness of transition economy

competition systems varies dramatically, but a number of jurisdictions – including South Africa,

4

See William E. Kovacic, Getting Started: Creating New Competition Policy

Institutions in Transition Economies, 23 Brook. J. Int’l L. 403, 403-08 (1997) (describing

creation of competition policy systems as element of law reform in transition economies).

2

�Brazil, Hungary, Mexico, Poland, South Korea, and Taiwan – have credible programs. Most new

regimes imitate the EU and the United States and reach offshore conduct that has significant effects

in the domestic market.

Consequences of Extraterritoriality and Multiplicity

The growth in the number of competition laws and the broad acceptance of EU and U.S.

concepts of extraterritoriality have major implications for cross-border commerce. One consequence

is an increase in the cost of complying with requirements for report mergers. Firms active in global

commerce may be required to notify dozens of jurisdictions. This phenomenon has raised the

question of whether valid competition policy goals might be achieved at lower cost through

acceptance of common notification procedures.

A second consequence of multiplicity and extraterritorial application of competition laws

is that the same behavior might be evaluated under divergent substantive standards. This possibility

became apparent in the different outcomes achieved in the EU and the United States, respectively,

in the Boeing/McDonnell Douglas and General Electric/Honeywell mergers.5 Disputes between EU

and U.S. antitrust agencies are rare, but they indicate the complications that companies face in

determining whether a transaction will withstand antitrust scrutiny.

A third consequence involves procedural differences. Private rights of action offer an

5

On the Boeing/McDonnell Douglas merger, see William E. Kovacic,

Transatlantic Turbulence: The Boeing-McDonnell Douglas Merger and International

Competition Policy, 68 Antitrust L.J. 805 (2001). On General Electric/Honeywell, see Timothy

J. Muris, Merger Enforcement in a World of Multiple Arbiters (Dec. 21, 2001) (prepared remarks

before the Brookings Institution Roundtable on Trade & Investment, Washington, D.C.),

available at .

3

�illustration. The United States gives private parties unique power to enforce antitrust laws.6

Successful private claimants are entitled to treble damages and attorneys fees. Compared to other

jurisdictions, U.S. civil procedure more readily entertains the certification of classes of injured

parties.

Recognizing the attractions of the U.S. system, foreign claimants increasingly have filed suits

in the United States to challenge cartel behavior that has effects inside and outside the United

States.7 These cases have raised the issue of whether the United States should serve as a treble

damage forum for the world – a venue for compensating foreign claimants when the cartel that

inflicts offshore harm also injures parties in the United States.

Recent decisions of the U.S. courts of appeals have disagreed about whether the Foreign

Trade Antitrust Improvements Act of 1982 (FTAIA)8 permits such claims to be brought in the U.S.

courts.9 On one level, the disagreement in the courts hinges on varied interpretations of the FTAIA’s

difficult provisions. Perhaps more interesting, the courts of appeals have debated the deterrence

effects of entertaining foreign claims. On the one hand, granting foreign claimants broad recourse

6

The private right of action in U.S. antitrust law is described in Andrew I. Gavil et

al., Antitrust Law in Perspective: Cases, Concepts and Problems in Competition Policy 923-26

(2002).

7

Notable examples include United Phosphorus, Ltd. v. Angus Chem. Co., 322 F.3d

942 (7 Cir. 2003) (en banc); Empagran S.A. v. F. Hoffman-Laroche, Ltd., 315 F.3d 338 (D.C.

Cir. 2002); Kruman v. Christie’s International PLC, 284 F.3d 384 (2d Cir. 2002); Den Norske

Stats Oljeselskap As v. HeereMac Vof, 241 F.3d 420 (5th Cir. 2001), cert denied, 122 S. Ct. 1059

(2002).

th

8

15 U.S.C. § 6a.

9

In the cases cited supra in footnote 7, defendants have succeeded in invoking the

FTAIA to bar the plaintiff’s claims in HeereMac and United Phosphorus. Plaintiffs have

withstood such challenges in Empagran and Kruman.

4

�to the U.S. courts might deter cartels by increasing their exposure for misconduct. On the other

hand, inviting foreign claims might undermine the operation of U.S. and foreign leniency programs

that reduce the punishment for a cartel member that is the first to inform the government about the

cartel’s activities.10

A fourth area of concern involves institutional capability. Many emerging market economies

that recently have enacted competition laws face daunting challenges in building the institutional

foundations for successful implementation. Correcting weaknesses in the relevant institutions – the

competition authority and collateral bodies such as the courts – is essential if enforcement is to

improve economic performance.11

Networks, Norms, and Convergence: The New Institutions of Competition Policy

The global development of competition law supplies a dramatic example of the “bottom up”

development of norms. Progress toward widely-accepted norms of competition policy substantive

standards, procedures, and levels of institutional capability might occur in three stages.12 The first

consists of decentralized experimentation within individual jurisdictions. The second stage involves

10

In deciding whether to use leniency measures to reduce the punishment imposed

by any single competition authority, a cartel member assesses the exposure it will incur from

other government authorities and other litigants (e.g., private claimants in the United States).

Estimating damages potentially owed to foreign claimants suing in U.S. courts might be so

uncertain that the firm declines to seek leniency, and the cartel’s detection is delayed. On the

use of leniency to detect cartels, see Gary R. Spratling, Detection and Deterrence: Rewarding

Informants for Reporting Violations, 69 Geo. Wash. L. Rev. 798 (2001).

11

See Kovacic, Institutional Foundations, supra note 1, at 301-10 (describing

common weaknesses in transition economies in institutions necessary to implement competition

laws).

12

This discussion uses the model of convergence presented in Timothy J. Muris,

Competition Agencies in a Market-Based Global Economy (Brussels, Belgium, July 23, 2002)

(Prepared remarks at the Annual Lecture of the European Foreign Affairs Review), available at

.

5

�the identification of best practices or techniques. In the third stage, individual jurisdictions

voluntarily opt in to superior norms.

Many international institutions are facilitating the process of convergence sketched above.

One is the ICN. Created in the Fall of 2001, the ICN is a virtual network of competition authorities

representing nearly 80 jurisdictions. The ICN operates through working groups consisting of

government officials and representatives from academia, consumer groups, legal societies, and trade

associations. One noteworthy initiative has focused on merger control and, among other measures,

has prepared a widely-praised body of guiding principles and best practices for notification practices

and procedures. Two other working groups are addressing competition advocacy and capacity

building in emerging markets.

ICN’s main contribution is likely to consist of helping form an intellectual consensus about

competition policy norms. The effort to accomplish this objective seems certain to alter the way

competition agencies define their role and set priorities. Success in developing widely accepted

international competition policy norms will require agencies to devote more resources to institution

building, perhaps by taking some resources that would have been devoted to prosecuting cases.

The requirements of institution-building pose difficult choices for competition authorities.

Academics and practitioners tend to grade competition agencies by the cases they prosecute.

Generating support to commit resources to construct an effective global competition policy

infrastructure requires convincing external constituencies that investments in institution building are

vital to the enforcement activities that historically have been taken as the measure of competition

agencies.

The internationally-driven transformation of how competition agencies will operate in the

6

�future has another important dimension. Leadership in developing competition policy norms will

come to agencies that generate the best ideas. Achieving intellectual leadership demands substantial

investments in “competition policy research and development.”13 Research will provide necessary

means for any jurisdiction to identify superior norms and persuade others to opt in. Because

progress toward widely accepted norms is likely to be gradual, only a commitment to long-run

engagement will suffice.

The ICN is not the only instrument for developing global competition policy norms. The

World Trade Organization and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development are

but two of the global and regional networks that are devoting significant effort to competition policy

convergence issues. In these and other initiatives, the U.S. antitrust agencies and their foreign

counterparts are making ever greater investments in building institutions to create international

competition policy norms. Contributions to the intellectual foundations and institutions of

competition policy, not simply the prosecution of cases, promise to become increasingly important

to what antitrust agencies must do.

13

The concept of competition policy “R&D” is introduced in Timothy J. Muris,

Looking Forward: The Federal Trade Commission and the Future Development of U.S.

Competition Policy (New York, N.Y., Dec. 10, 2002) (Prepared remarks for the Milton Handler

Annual Antitrust Review), available at .

7

�

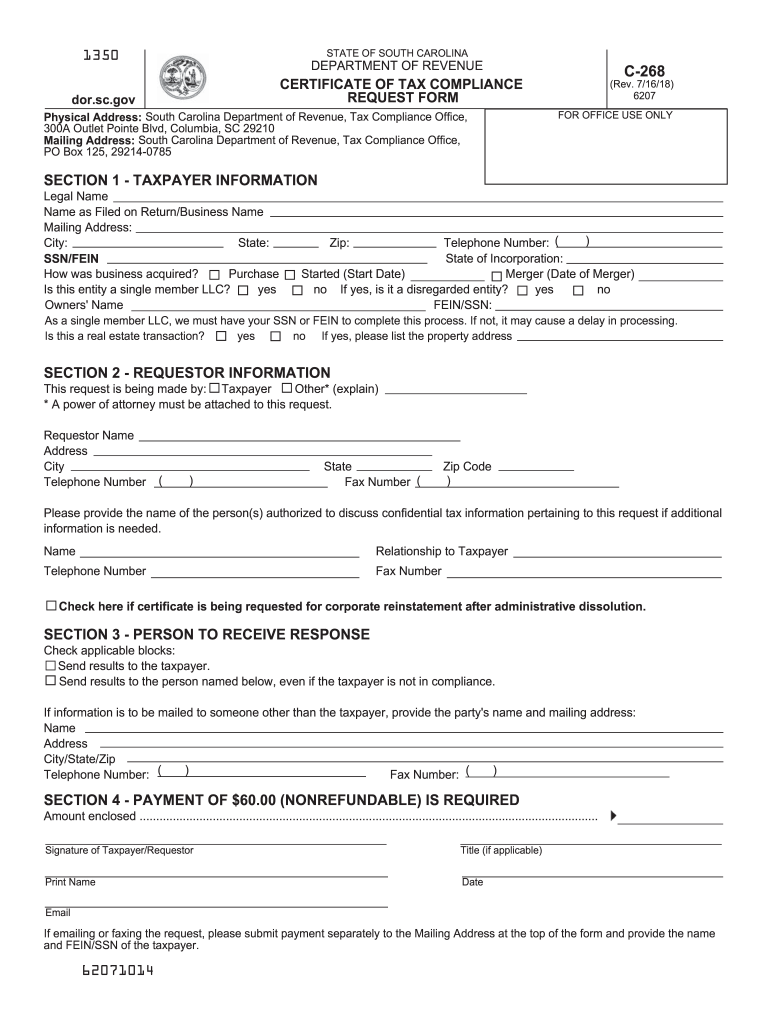

Practical advice on finalizing your ‘Sc Certificate Compliance 2018 2019 Form’ digitally

Are you fed up with the inconvenience of managing paperwork? Look no further than airSlate SignNow, the premier electronic signature solution for individuals and small businesses. Bid farewell to the lengthy process of printing and scanning documents. With airSlate SignNow, you can effortlessly fill out and sign documents online. Utilize the extensive features embedded in this user-friendly and cost-effective platform and transform your approach to document management. Whether you need to sign forms or gather signatures, airSlate SignNow facilitates everything seamlessly, with just a few clicks.

Adhere to this step-by-step guide:

- Log into your account or initiate a free trial with our service.

- Select +Create to upload a file from your device, cloud storage, or our template library.

- Open your ‘Sc Certificate Compliance 2018 2019 Form’ in the editor.

- Click Me (Fill Out Now) to set up the document on your end.

- Add and designate fillable fields for others (if required).

- Proceed with the Send Invite settings to request eSignatures from others.

- Save, print your copy, or transform it into a reusable template.

No need to worry if you have to collaborate with your colleagues on your Sc Certificate Compliance 2018 2019 Form or send it for notarization—our platform provides everything necessary to complete such tasks. Sign up with airSlate SignNow today and elevate your document management to the next level!