“This is the pre-peer reviewed version of the following article: McGregor, S. L. T. (2011).

Home Economics in higher education: Pre professional socialization. International Journal

of Consumer Studies, 35(5), 560-568, which has been published in final form at

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1470-6431.2011.01025.x/pdf . Authors’ rights

are detailed in the Copyright Transfer Agreement.”

Keywords:

home economics, pre professional socialisation, higher education, professional

identity, professional culture

Home Economics in higher education: Pre professional socialization

Abstract

It is paramount that higher education programs in home economics remain ever vigilant

regrading how they are designed because they socialise individuals into the profession, and

deeply affect the formation of home economics professional identities, how people see

themselves as a home economist and identify with the profession. This paper discusses the link

between higher education home economics programs and future-proofing the profession through

a well-thought out pre professional socialisation process. Well-planned socialisation processes

better ensure a commitment to the home economics professional culture and community, and to

deeply entrenched alignment with a positive home economics identity.

The premise of this paper is two-fold. First, higher education home economics degrees,

and the attendant socialisation process, deeply affect the formation of professional identity.

Second, strong professional identity with the profession is a powerful tool to future-proof the

profession. Schein (1978) describes professional identity as the relatively stable and ensuring

constellation of attributes, beliefs, values, motives and experiences by which people define

themselves in a professional role. Professional identity forms over time but it is most adaptable

and mutable early in one’s career (Ibarra, 1999). As well, it differs from, but is inherently linked

with, one’s professional image or persona, the impressions one conveys to others of oneself as a

professional, and by association, that of the entire profession (Ibarra).

For this reason, the role that higher education degree programs play in the development of

home economists’ professional identity warrants ongoing attention. At the end of a higher

education degree, home economics graduates should have both (a) the technical competencies

(knowledge, concepts, content and theories) and (b) the internalized values, philosophy, mission

and cultural identity embraced by members of the profession (Cornelissen, 2006; Kieren, Vaines

& Badir, 1984). This higher education experience is intended to help home economists continue

to meet the challenges they face in their careers, and the challenges faced by individuals and

families. As the profession moves into the 21st century, it is important that this topic be revisited

because, as noted, the socialisation process that people experience in university plays a key role

in future-proofing the profession.

To address this topic, the paper first defines the concept of higher education and then

reviews the literature on discussions of home economics in higher education (the last 40 years,

Page 1 of 15

�admittedly from a North American perspective although the import of not future-proofing the

profession in all regions will be felt world-wide). This literature review illustrates that little has

been said to date about the role of higher education programs in home economics and their role

in future-proofing the profession through the socialisation process.

This paper takes up that topic by discussing the pre professional socialisation process

(intent and stages) in home economics higher education programs, followed by five ideas about

how to future-proof the profession from the perspective of pre professional socialisation. The

paper concludes with a discussion of three basic approaches to designing higher education

program curricula (stand-alone, infuse and integrate) and how each serves the purpose of pre

professional socialisation. The final conclusion is that pre professional socialisation should not

be left to chance. It needs to be planned, coordinated and nurtured; our future depends upon it.

Higher Education Defined

For clarification, higher education is a term that refers to the level of education beyond

high school (or its equivalent) that is provided at universities and colleges, which award

academic degrees or professional certifications. This level of education (also called higher

learning and tertiary learning) can involve bachelor, master and/or doctoral degrees, as well as

post-doctoral studies. One of the main purposes of higher education is to help adults negotiate

their membership into an encompassing culture (Bruffee, 1998), including the professional home

economics culture.

The foundational knowledge gained in higher education, which shapes students into

professional home economists, circumscribes their lives; they never entirely outgrow this

knowledge (see Bruffee, 1998). For this reason, it is paramount that higher education programs in

home economics remain ever vigilant of how they are designed because they socialise individuals

into the profession.

Historical Discussions of Home Economics in Higher Education

During the past 40 years, several scholars have written about home economics in higher

education, from a variety of perspectives. These contributions are introduced and discussed

chronologically.

Seventies

Marshall (1973) identifies four issues affecting the future of home economics in higher

education, including specialization versus generalization, and gendered roles. Harper (1975)

reflects on the status of home economics programs in higher education in the United States from

1952-1973, reporting on enrolment, gender, degrees granted and under represented

specializations. Hawthorne (1978) discusses the cohesiveness of home economics as a discipline

in higher education, arguing that cohesiveness makes home economics a viable discipline.

Eighties

Firebaugh (1980) provides an overview of seven trends in home economics higher

education programs in the United States, including name changes, diversification of student

bodies, and the need for cohesive curricula, a common philosophical commitment and

purposively articulated linkages between general program components and specialization areas.

She argues for interdisciplinary programs and cross-disciplinary attitudes while keeping a clear

focus on families. Most especially, she asserts that home economists must be at the fine cutting

edge of their field and committed to the purposes and philosophy of home economics (see also

McGregor, 2011).

Page 2 of 15

�Horn (1981) comments on the status of home economics programs in higher education,

advocating for a pre-home economics program (much like pre-law or pre-medicine). Horn also

calls for a holistic philosophy, which entails returning to large-scale systems thinking so we can

put the parts back together again (especially the many fragmented specializations within home

economics higher education programs). Greninger, Hampton, Kitt and Durrett (1986) discuss the

impact of funding trends on higher education home economics programs in a changing economic

environment. Harper and Davis (1986) share an analysis of trends in American home economics

higher education programs from 1968-1982. In particular, they refer to a pervasive negative

identity that needs to be dispelled by emphasizing the competencies possessed by home

economists that enable them to improve family well-being and quality of life.

Nineties

In the 1990s, a theme issue of Kappa Omicron Nu FORUM was devoted to the place of

family and consumer sciences (FCS) in higher education (Spring 1995, volume 8, issue 1). The

issue contains eight articles. As per the topic of this paper, Fahm (1995) discusses a philosophy

of viability for home economics higher education programs (to be discussed shortly) as well as

identity and the need for mission alignment.

In Europe, Turkki (1996) clarifies the role of research in promoting home economics in

higher education. She asserts that home economics research has the potential to strengthen the

position of the discipline in society because it is an opportunity to “reveal the meaning of Home

Economics issues” (p. 359). She also examines the challenges of integrating a holistic

perspective into home economics higher education curricula (Turkki, 1997). “A holistic view [of

home economics education at the university level] contains an awareness of the meaning of the

nature and culture behind our [professional] activities” (1997, p.167).

Mitstifer (1999) reports on an open summit on the future of home economics in higher

education in the United States. The intention of the summit was to develop a unified direction for

FCS in higher education so as to serve the common good of the FCS higher education

community. The impetus for the summit was one practitioner’s challenge to others “to take

charge of our professional identity” (p.1).

2000s

Lichty and Stewart (2000) explore the socialisation process of new faculty members in

home economics higher education programs. They focus on the stress and rewards faced by new

faculty members as they learn the ropes of being a university academic in the field of home

economics. Cornelissen (2006) studies the professional socialisation process of home economics

students in higher education programs in South Africa. Dallmeyer, Randall and Collins (2008)

examine the role of home economics higher education programs in the United States in

promoting socially responsible behaviour in graduates.

None of these initiatives discuss the link between higher education home economics

programs and future-proofing the profession through a well-thought-out pre professional

socialisation process. The next section addresses this idea. For clarification, if a profession is

future proofed, it is protected, guaranteed not to be superceded by unanticipated future

developments. A future-proofed profession can handle the future because members of the

profession take steps now in order to avoid having to make radical changes to practice in order to

remain viable in the future. A profession that is future-proofed will not stop being effective

because something newer or more effective comes in to replace it. A future proofed profession is

Page 3 of 15

�strategically planned so it can remain effective even, especially, when things change. Future

proofing entails “anticipating future developments to minimize negative impacts and optimize

opportunities” (Pendergast, 2009, p.517), always to ensure relevancy, viability and vitality.

Pre Professional Socialisation for Home Economics in Higher Education

von Schweitzer (2006) suggests that the mission of the home economics profession is to

gain systematic insight into the processes that constitute the human nature of the family as an

institution. She notes this mission requires systematic knowledge about humanness, complex

realities, life mastery, human potential, human/nature relationships, large life forces, generational

equity, and daily energy expended on the culture of family life.

Another commonly stated mission of home economics is that practitioners are intended to

enable individuals and families to cope with, adapt to and affect change. They are expected to

build and maintain a system of actions (mental processing) that helps them mature as individual

family units and become stronger as a social institution. This approach leads to family members

engaging in enlightened, cooperative participation in the critique of society, and in the

formulation and achievement of social goals (Brown & Paolucci, 1979). McGregor (1997) shares

a lay-discussion of the intellectual dimensions of this complex mission statement.

In effect, home economics is more than an academic discipline. It also is a missionoriented profession (like medicine and education), one that creates knowledge for the sake of

using it in practice, rather than for just having more knowledge (Brown & Paolucci, 1979;

Vaines, 1980). To become academically and philosophically qualified to assume the

responsibilities of practicing in a mission-oriented profession, individuals obtain one or more

degrees from higher education institutions. It is within these faculties, departments, programs and

units of higher education that pre professionals learn how to “be” a home economist (Horn,

1981).

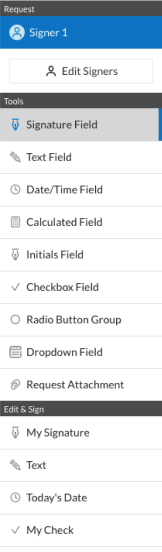

Stages of Intentionally Planned Socialisation Process

In an ideal world, they would undergo an intentionally planned socialisation process (see

Figure 1, drawn from Weidman, Twale and Stein, 2001). Students would move from novices

informed by lay perceptions of the profession through a degree program ideally designed to help

them internalize and commit to an identity as a professional home economist. Professional

socialisation is “the process by which people selectively acquire the values and attitudes, the

interests, skills and knowledge – in short, the culture – current in groups of which they are, or

seek to become, a member” (Merton, Reader & Kendall, 1957, p. 278). The intent of

socialisation is to help them acquire the knowledge, skills, philosophy and sense of identity that

are characteristic of being a home economist (Cornelissen, 2006).

The socialisation process involves the internationalization of the values and norms of the

profession into one’s own behaviour and self-concept (Cornelissen, 2006). Pre professionals

(novices to the profession) enter the higher education program with one set of values and, if

successfully socialised, leave with a deeply entrenched value of the home economics profession,

especially the philosophical core of the profession (McGregor, 2011). When values change,

behaviour can change, leading to changes in self-concept and self-identity to such an extent that

an “identity develops within and for the profession” (Cornelissen, p.50). The structure and

composition of home economics higher education programs “form the very basis of our whole

identity” (Turkki, 2008, p.36). “The quality of the program ... affect[s] the thoroughness and

success of the total socialisation process” (Weidman et al., 2001, p.13).

Page 4 of 15

�Figure 1 Stages of pre professional socialization (Weidman et al., 2001)

How pre professionals come to understand the home economics profession hinges on

higher education programs. Because the intellectual and philosophical rigour of these programs

has such a profound impact on the profession, we must continually ask if the curricula need to be

reframed to ensure the future progress of the profession (future proofing). In a synopsis of a

summit on home economics in higher education, Mitstifer (1999) suggests it is critical that

professionals “encourage alignment [not agreement] in developing a common, chosen destiny”

(p. 2). A key tool in this identify-formation process is the completion of a higher education

degree in home economics.

Suggestions for Future Proofing Home Economics in Higher Education

Socialisation and recruitment into professions tends to be governed by the most powerful

segments of a profession, one segment being higher education institutions (Clouder, 2003); that

is, the academy. The academy (a term used to refer to the collection of institutions and processes

comprising higher education) must succeed in its role as the major socialising agent for members

of the profession; the viability of home economics depends upon the academy. The academy

must: (a) create appropriate programs of study, (b) be engaged in relevant research and (c) help

home economists make lasting connections to society (Clouder). Pre professional socialisation is

the cornerstone of this obligation.

This section identifies five forward-thinking ideas for consideration within the academy

as efforts are made to future-proof the profession and the discipline: (a) foster a cultural identity

as a home economist, (b) cultivate a professional identity, (c) socialise the Evolving Professional,

(d) frame home economics in higher education curricula, and (e) employ a viability philosophy

when (re)designing curricula and pre professional socialisation initiatives. Each is now discussed.

Page 5 of 15

�Cultural Identity as Home Economists

All professions require a formal period of professional socialisation (Hoyle & John,

1995), serving to orient newcomers to the culture of the profession. Higher education in home

economics plays a vital role in assisting pre professionals to understand their cultural identity as

home economists. Through a process of acculturation (the adoption and assimilation of an

unfamiliar culture), home economics degrees socialise people into the profession. Through these

degree programs, pre professionals should gain deep insights into what it means to “be” a home

economist.

Higher educational experiences for pre professional home economists should include: (a)

a KAS component (knowledge, attitudes and skills); (b) a cultural component (normative,

ethical practice); and, (c) a philosophical component (mission, values, principles). Within all

three components, it is possible to help students gain a sense of ‘a calling to the field’ (Hayden,

1995). Done properly, home economics higher education programs contribute to pre

professionals appreciating and embracing shared goals, values and a common professional

identity. This education also acculturizes them to be inclined to adopt and to participate in the

professional home economics culture, during and after university (Cornelissen, 2006; Kieren et

al., 1984).

Professional Identity Cultivation

Weidman et al. (2001) identify three core elements that lead to identification with and

commitment to a profession: knowledge acquisition, investment and involvement (see Figure 2).

Kleine, Kleine and Laverie (2006) refer to this as identity cultivation, explaining that single roles

exist within a portfolio of role identities that define the global self. Weidman et al.’s (2001)

model readily applies to home economics higher education programs.

Figure 2 Core elements of professional identification and commitment (Weidman et al.,

2001)

Firstly, pre professionals must acquire cognitive knowledge, affective knowledge and

understandings of the problems and ideologies that characterize the profession. As they acquire

this knowledge, it moves from being general to specialized and much more integrated and

complex. They develop theoretical insights as well as value orientations (Weidman et al., 2001).

Page 6 of 15

�Secondly, through the process of investment, pre professionals develop a role identity as a

home economist and they develop a commitment to the profession. They invest in the profession

by committing something of personal value, usually money, time, alternative career choices,

social status and/or reputation. Through persistent and consistent engagement with the degree

program, they manifest professional commitment (Weidman et al., 2001).

In more detail, Kleine and Kleine (2000) outline five states of role identity development

for freely chosen roles, applied here to home economics: (a) pre-socialisation (lay knowledge of

what it means to be a home economist); (b) identity discovery and exploration to determine how

well the role of being a home economist would complement or extend other identities comprising

the person’s self-definition; (c) identity construction via actively choosing to devote time and

energy to the pursuit of the identity (investment in higher education degree programs); (d)

identity maintenance, including refinement and ongoing reconfirmation through labeling oneself

as a home economist; and, (e) identity disposition (temporary or permanent), wherein people

decide whether or not the role is relevant for them anymore.

The third element of professional identity cultivation is involvement (Weidman et al.,

2001). By acquiring and internalizing knowledge, attitudes, skills, norms and values of the

profession, people can integrate a professional role into their concept of self, thereby creating a

professional identity and a professional self-image of being a home economist. Couple this with a

high valuation of the profession, participation in it and a willingness to be identified as a member

(called professional attraction), and the novice is much more likely to become a committed

home economics professional.

In summary, the acquisition of specialized knowledge and skills, coupled with

participation in formal preparation for a professional role (investment in a degree program),

promotes identification with and commitment to a professional role (involvement and

professional attraction) (Weidman et al., 2001).

Socialising the Evolving Professional

Tsang’s (2009) new concept, the Evolving Professional (EP), is very pertinent for home

economics. The Evolving Professional concept assumes that students evolve as a professional,

they develop gradually (evolve is Latin volvere, to roll). Higher education programs must be

designed in such a way that specific professional attributes are developed and internalized,

thereby enhancing newcomers’ potential for success upon graduation and entry into the

profession. Tsang proposes that “the way of being” a professional cannot be assumed to be a

natural by-product of higher education but must be explicitly developed and practiced; rarely

does this happen. “At best it is considered ‘assumed knowledge,’ ‘tacit knowledge,’ ‘the hidden

curriculum,’ ‘threshold concepts,’ and ‘troublesome knowledge’ that cannot be or need not be

taught” (p.2).

Done properly, professional socialisation in higher education empowers students by

providing a context and reasons for deep learning, leading to a clearly defined professional

identity. Carefully planned higher education programs are needed to explicitly guide students “to

become” and to “walk the talk” (Tsang, 2009, p.2). These programs need to be designed in such a

way that students can integrate and internalize: (a) what they know, (b) what and how they

practice and (c) who they become (their ways of “being” a professional).

The Evolving Professional needs to be socialised to be self aware and to be able to

“construct their own meanings and perspectives - to be clear in their own minds about their

Page 7 of 15

�professional identity, their professional ways of thinking, and their professional ways of

becoming” (Tsang, 2009, p.2). As well, “the ‘involved professional’ is able to participate in

shaping the dynamic professional culture in which s/he is engaged, informed by professional

knowledge which [lay people] do not possess” (Boyask, Boyask & Wilkinson, 2004, p.3).

Framing Home Economics in Higher Education

Upon leaving higher education programs, home economists will make sense of the world

around them by framing events through their professional, philosophical lens, deeply informed

by the socialisation process and attendant course work and learning experiences. The essence of

framing is the selection and prioritization of facts, events or developments over others, thereby

promoting a particular interpretation of the profession. The way members of the profession

frame home economics effects what they expect from situations, and from the people around

them. Frames lead home economists in certain directions, and to particular assumptions and

conclusions (Norris, 1996). Frames have a profound impact on professional actions. It is

inevitable that particular frames become the conventional way to see and to treat the profession

(cf. McGregor et al., 2004; Pendergast & McGregor, 2007).

How home economics graduates choose to present themselves and the profession to the

world (i.e., frame home economics) is deeply influenced by the higher education socialisation

process. Home economics graduates make (un)conscious decisions about how to negotiate their

daily life as a home economist - decisions about how they present themselves to the public (see

Goffman, 1971). These decisions can mirror how they are responding to others’ expectations of

what constitutes home economics. As well, they can assume proactive positions, with

practitioners actively choosing to be ambassadors of the profession, presenting themselves to the

public with a sense of pride and legitimacy (McGregor & Goldsmith, 2011; Pendergast &

McGregor, 2007). Either response is partially shaped by their higher education socialisation

process, and how the designers of their home economics degree(s) framed home economics. Put

simply, but profoundly, “individuals construct their profession, which, in turn, constructs

individual professionals,” with higher education programs being a major influencing factor

(Clouder, 2003, p.220).

A Viability Philosophy for Redesigning Higher Education Degrees

The philosophy, theoretical orientations, conceptual frameworks and competencies that

are instilled in pre professionals in higher education programs have a dramatic impact on the

vitality of home economics as a discipline (Turkki, 2008). Also, higher education degrees are a

major aspect of developing the home economics profession. If there is a deficit of people

educated to be home economists, and if there is a deficit in their actual education, the progress of

the profession will be adversely affected (not future-proofed). This responsibility falls on higher

education administrators and program planners.

The past accomplishments of home economics in higher education are a credit to

administrators, professional leaders, scholars and graduates who practice with distinction in

professional and personal endeavors (Harper & Davis, 1986). But, this same cadre of people also

is responsible for any shortcomings of home economics in higher education. The most important

challenge to home economics higher education programs and units is to adequately prepare the

next generation of practitioners and to do so using a philosophy for home economics viability

(Fahm, 1995). Part of this viability philosophy is curricula revision and transformation to ensure

that programs remain responsible for the development of visionary leaders who can stimulate

Page 8 of 15

�new approaches to challenges in uncertain futures (Fahm). A key component of these academic

programs is socialisation into, and cultural identification with, home economics as a missionoriented profession and an academic field of study.

Three Curriculum Socialisation Design Strategies

Page (2004) views professional socialisation as the acquisition of values, attitudes, skills,

knowledge and dispositions pertaining to a professional subculture, making individuals more or

less effective members of that profession. He believes socialisation is a subconscious process

whereby individuals internalize behaviourial norms and standards and form a sense of identity

and commitment to a professional field (see also Cornelissen, 2006 and Weidman et al., 2001).

Conversely, Klossner (2008) maintains that consciously and deliberately planned control of the

socialisation of preservice students can influence their professional preparation and growth as

they become credentialed members of the profession.

Many factors positively and negatively affect the professional socialisation and identity

development of students (Klossner, 2008). This paper maintains that one of the key determinants

is the curricula of higher education programs where students are socialised into the profession

and where they gain their inaugural philosophical orientation. Research shows that the influence

of the complex process of professional socialisation is long lasting (Page, 2004), making the

content of the higher education curricula especially significant. A key role of home economics

higher education programs is to identify and to teach about the ties that bind home economics

together as an academic field and that bind its practitioners together as professionals - a unifying

bond. Graduates of these programs should be socialised to clearly and forcefully stress their

professionalism and the contributions that professional home economists make to society

(Marshall, 1973).

Horn (1981) believes home economics has the potential to be “a weight-bearing pillar that

undergirds society” (p.21). To that end, well-thought out higher education home economics

programs become the crux of future-proofing the profession. Architects of home economics

curricula are urged to design formal pre socialisation programs that ensure professional

momentum, generate synergy, improve communications, stimulate innovation, and ensure clear,

far-reaching peripheral vision of practitioners (McGregor, 2006). This purposeful program design

is required because the context within which novices experience socialisation has a powerful

influence on the development of their self-identity and of their professional identity (Clouder,

2003). The resultant acculturation process is capable of producing a personal transformation

(Clouder), moving the person from novice to emergent professional to an incumbent of the

profession and, finally, to the status of credentialed practitioner (Cornelissen, 2006).

How higher education practitioners understand pre professional socialisation may impact

on the types of curricular decisions they make, both in undergraduate and in graduate home

economics education. Among other things, it will affect how they design curricula intended to

help students develop a professional identity and a self-concept and to identify with the home

economics professional community and culture. Education that fosters an involved, cultivated,

evolving professional identity will require academics to recognize that home economics practice

is socially constructed within higher education programs as is the development of a commitment

to a professional community (Boyask et al., 2004). Each of three approaches to curricular design

are now discussed: stand-alone, infused and integrated.

Page 9 of 15

�Standalone Course

Curriculum architects can choose from several strategies as they design their socialisation

process (see Figure 3). First, they can create or update a standalone Introduction to the

Profession course, which only novice students take in their first year (or, in some cases, only

senior students take in their final year). This course contains content pertaining to the history,

contemporary and future directions of the profession. Students learn about the mission, the goals

and values of the profession, the key practice competencies, and the prevailing philosophy.

Ideally, the responsibility for the preparation and delivery of this course would rotate among

faculty members, better ensuring across-the-board buy-in of the important aspects of professional

socialisation.

Figure 3 Three curriculum socialization design strategies

As well, ideally, all students in the program would be required to take the course,

regardless of their specialization; however, they only would be exposed to this information in

their novice year, with no ongoing orientation as they moved through the socialisation process.

Conversely, taking the course in the year one graduates precludes students from benefitting from

any scaffolding orientation to the profession (see Figure 1). In either case, truncated socialisation

would occur due to intentionally planning for one compulsory course with no continuity or

reinforcement across the duration of the degree. This approach is preferred to no socialisation

course at all.

Infuse into All Courses

Second, curriculum architects could eschew the one-time, compulsory course and instead

prepare agreed-to content (as per above) that would be infused into all courses in the higher

education degree(s), ideally in all specializations. Ideally, all faculty members would be inserviced to this content so they would feel comfortable using it in their individual, respective

Page 10 of 15

�courses. This approach would open possibilities for the home economics perspective to permeate

the entire degree, from year one to graduation, thereby socialising students to what it means to be

a home economist, despite their specialisation (or within the context of their specialisation).

Each of novice, apprentice, mature novice and emerging professional would remain

continually exposed to an orientation to home economics professional identity and culture;

however, from this approach, there would be no attempt to integrate learnings across students,

specializations or years invested in the degree. As well, there would be a risk that the agreed-to

content (per the standalone course) would be woven into courses only at the discretion of

individual instructors. Furthermore, the degree to which individual instructors embrace and

internalize the course content will affect their willingness and ability to infuse it into their

teachings. Regardless, the infused approach is better than the standalone approach, in principle.

Integrated Approach

Third, curriculum architects could opt for an integrated approach. They could co-prepare

an introductory course, co-in-service all faculty members to the ideas in that course, ask all

faculty to use those ideas in their respective courses, and also purposively make connections

across all specializations and all undergraduate and graduate degrees. They could create

opportunities for all students to work together with home economics knowledge, theories,

competencies and philosophies until they begin to see patterns emerge and connections are born

about what it means to “be” a home economist. Through this integrated approach, a richer

orientation to identity cultivation and professional evolution would be ensured. Faculty members

would co-create and co-use thematic units, issues-based learning, inquiry-based learning,

problem posing, and a problem-based, experiential, active learning pedagogy.

This is a powerful approach to help neophytes, veteran newcomers, mature novices and

emerging professionals internalize a healthy home economics identity and self-image. A

challenge with this approach is the ability to find people who are committed to an ongoing

involvement with long-term, integrated pre professional socialisation in addition to everything

else that academics are tasked to perform.

Further Clarification

To recap, using this model (see Figure 3), curricula designers have three options: develop

a compulsory, standalone course; infuse ideas into all courses; or, integrate ideas and experiences

across the entire program(s) for the duration of the degree(s). Without prioritizing them, it is

important to appreciate their subtle yet definite distinctions.

In more detail, something that is standalone is able to operate, function or exist without

assistance or additional support. However, while independent, a standalone course orienting

students to the profession is not connected to anything else, nor does it require connections to

other courses to function as intended. When a standalone course is used, only a small group of

people have access to the content, not the entire group and not for very long.

Infusion refers to soaking or steeping something in something else to the point that the

infusion pervades everything (e.g., steeping tea in water). The steeping process enables

something to release its active ingredients. The amount of time something is steeped depends

upon the purpose of the preparation. An infused curricular approach to a home economics

identity strives to instill ideas in people by gradually but firmly establishing the ideas or attitudes

about home economics culture and identity in individuals’ minds. Once infused, it is very

difficult to separate or disconnect.

Page 11 of 15

�Integration refers to combining things in order to make things complete. By incorporating

ideas across the entire learning experience, by bringing home economics students and ideas

together, an integrated approach forms or unites things into a whole. In the case of pre

professional socialisation, an entire new person emerges at the end of an integrated higher

education program - a professional home economist. Integrate also can mean to renew, repair or

to begin again, all tantamount to preparing an evolving home economics professional who

embraces the culture, knowledge base and philosophy of the profession - moving from novice to

emergent, credentialed professional.

Conclusions

Pre professional socialisation should not be left to happenstance. Why not? One of the

most important outcomes of professional socialisation is an evolving professional identity,

whereby novices become deeply aware of their ability to fully participate in the professional

culture and the discipline as a whole (McGregor, 2011; McGregor & Goldsmith, 2010). Once

emergent professionals graduate and become credentialed practitioners, they have an opportunity

to influence and propagate the home economics professional culture and the attendant body of

knowledge. They can more readily assume this responsibility if the socialisation process they

experienced at college or university helped them cultivate a positive professional identity and self

image as a home economist. Turkki’s conviction bears repeating: the structure and composition

of home economics higher education programs “form the very basis of our whole identity” (2008,

p.36). Their design cannot be left to chance.

Davis (1993, 2008) maintains that, because home economics transcends national borders,

the basic principles of home economics are the same, worldwide. However, practitioners

applying these principles will have to adapt them to local cultures and politics while still

retaining their coherence, because the context for the socialisation process and forward-evolution

of the profession is different in each country. Indeed, some already appreciate this diversity

(Wahlen, Posti-Ahokas & Collins, 2009). Within the context of this diversity, the ideas in this

paper should appeal to an international audience; the need to continually revisit higher education

home economics programs applies around the world. This paper reinforced the need to continue

to engage with the issue of home economics in higher education, especially as it influences

professional socialisation, identity formation, cultural orientation and philosophical orientations

of what it means to “be” a home economist.

References

Boyask, D., Boyask, R., & Wilkinson, T. (2004). Pathways to ‘involved professionalism.’

Medical Education Online, 9. Retrieved from

http://www.med-ed-online.net/index.php/meo/article/view/4367/4549

Brown, M., & Paolucci, B. (1979). Home economics: A definition [mimeographed]. Alexandria,

VA: AAFCS.

Bruffee, K. A. (1998). Collaborative learning (2nd ed). Baltimore, MA: John Hopkins University

Press.

Clouder, L. (2003). Becoming professional. Learning in Health and Social Care, 2(4), 213-222.

Cornelissen, J. (2006). Professional socialization of family ecology and consumer science

students at South African universities. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of

Page 12 of 15

�Stellenbosch. Retrieved from http://etd.sun.ac.za/bitstream/10019/39/1/CorneJJ.pdf

Dallmeyer, M., Randall, K., & Collins, N. (2008). Home economics in higher education.

International Journal of Home Economics, 1(2), 3-9.

Davis, M. L. (1993). Perspectives on home economics: Unity and identity. Journal of Home

Economics, 85(4), 27-32.

Davis, M. L. (2008). On identifying our profession. International Journal of Home Economics,

1(1), 10-17.

Fahm, E. G. (1995). Home economics in higher education. Kappa Omicron Nu FORUM, 8(1),

44-56.

Firebaugh, F. M. (1980). Home economics in higher education in the United States: Current

trends. Journal of Consumer Studies and Home Economics, 4(2), 159-165.

Goffman, E. (1971). The presentation of self in everyday life. London: Penguin.

Greninger, S., Hampton, V., Kitt, K., & Durrett, M. (1986). Higher education home economics

programs in a changing economic environment. Home Economics Research Journal,

14(3), 271-279.

Harper, L. J. (1975). The status of home economics in higher education. Journal of Home

Economics, 67(2), 7-10.

Harper, L. J., & Davis, S. L. (1986). Home economics in higher education. Journal of Home

Economics, 78(2), 6-17, 50.

Hawthorne, B. E. (1978). The cohesiveness of home economics as a discipline in higher

education. Paper presented at the American Home Economics Association Conference.

New Orleans, LO: AHEA.

Hayden, J. (1995). Professional socialisation and health education preparation. Journal of Health

Education, 26(5), 271-276,.

Horn, M. (1981). Home economics: A recitation of definition. Journal of Home Economics,

73(1), 19-23.

Hoyle, E., & John, P. (1995). Professional knowledge and professional practice. London,

England: Cassell.

Ibarra, H. (1999). Provisional selves: Experimenting with image and identity in professional

adaptation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(4), 764-791.

Kieren, D., Vaines, E., & Badir, D. (1984). The home economist as a helping professional.

Winnipeg, MB: Frye Publishing.

Kleine, R. E., & Kleine, S. S. (2000). Consumption and self-schema changes throughout the

identity project life cycle. Advances in Consumer Research, 27, 279-285.

Kleine, S. S., Kleine, R. E., & Laverie, D. (2006). Exploring how role identity development stage

moderates person-possession relations. In R. Belk (Ed.), Research in Consumer

Behaviour (Vol 10) (pp.127-173). San Diego, CA: JAI Press.

Klossner, J. (2008). The role of legitimation in the professional socialization of second-year

undergraduate athletic training students. Journal of Athletic Training, 43(4), 379-385.

Lichty, M., & Stewart, D. (2000). The socialization process of new college faculty in family and

consumer sciences teacher education. Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences

Education, 18(1), 19-37.

Marshall, W. H. (1973). Issues affecting the future of home economics. Journal of Home

Economics, 65(6), 8-10.

Page 13 of 15

�McGregor, S. L. (1997). Envisioning our collective journey into the next millennium. Journal of

Home Economics Education, 35(1), 26-38.

McGregor, S. L. T. (2006). Transformative practice. East Lansing, MI: Kappa Omicron Nu.

McGregor, S. L. T. (2011). Home economics as an integrated, holistic system: Revisiting Bubolz

and Sontag's 1988 human ecology approach. International Journal of Consumer Studies,

35(1), 26-34.

McGregor, S. L.T., Baranovsky, K., Eghan, F., Engberg, L., Harman, B., Mitstifer, D.,

Pendergast, D., et al. (2004). A satire: Confessions of recovering home economists.

Kappa Omicron Nu Human Sciences Working Paper Series. Retrieved from

http://www.kon.org/hswp/archive/recovering.html

McGregor, S. L. T., & Goldsmith, E. (2010). De-fogging the philosophical, professional mirror:

Insights from a lighthearted metaphor. International Journal of Home Economics, 3(2),

16-24.

Merton, R. K., Reader, G. G., & Kendall, P. L. (1957). The student physician. Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University Press.

Mitstifer, D. (1999). A synopsis of “FCS in Higher Education: An open summit on the future.”

East Lansing, MI: Kappa Omicron Nu. Retrieved from

http://www.kon.org/summit/smt_review.html

Norris, P. (1996, April). Gender in political sciences: Framing the issues. Paper presented at the

British Political Studies Association annual conference. Glasgow, Scotland: Glasgow

University.

Page, G. (2004). Professional socialization of valuation students. Proceedings of the 10th Pacific

Rim Real Estate Society Conference, Bangkok, Thailand. Retrieved from

http://www.prres.net/Papers/Page_Professional_socialization_of_valuation_students.pdf

Pendergast, D. (2009). Generational theory and home economics: Future proofing the profession.

Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 37(4), 504-522

Pendergast, D., & McGregor, S. L.T. (2007). Positioning the profession beyond patriarchy

[Monograph]. East Lansing, MI: Kappa Omicron Nu. Retrieved from

http://www.kon.org/patriarchy_monograph.pdf

Schein, E. H. (1978). Career dynamics: Matching individual and organizational needs. Reading,

MA: Addison-Wesley.

Tsang, A. K. L. (2009). Students as evolving professionals. Paper presented at the Australian

Association for Research in Education Conference. Canberra, AU: AREC. Retrieved

from Http://www.aare.edu.au/09pap/tsa09936.pdf

Turkki, K. (1996). The importance of research functions in promoting home economics

education in Finland. Journal of Consumer Studies and Home Economics, 20(4), 355361.

Turkki, K. (1997). The challenges of holistic thinking in home economics. In I. Musteikiene

(Ed.), Humanizmas, demokratija ir pilietiskumas mokykloje [Humanism, democracy and

citizenship education] (pp. 164-170). Vilnius, Lithuania: Vilniaus Pedagoginis

Universitetas.

Turkki, K. (2008). Home economics: A dynamic tool. International Journal of Home Economics,

1(1), 32-42.

Vaines, E. (1980). Home economics: A definition. A summary of the Brown and Paolucci paper

Page 14 of 15

�and some implications for home economics in Canada. Canadian Home Economics

Journal, 30(2), 111-114.

von Schweitzer, R. (2006). Home economics science and arts. Frankfurt, Germany: Peter Lang.

Wahlen, S., Posti-Ahokas, H., & Collins, E. (2009). Linking the loop: Voicing dimensions of

home economics. International Journal of Home Economics, 2(2), 32-47.

Weidman, J., Twale, D., & Stein, E. (2001). Socialisation of graduate and professional students

in higher education. ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report, 28(3), 1-118.

Page 15 of 15

�