Discover the Bill Book Sample in Word Format for Life Sciences

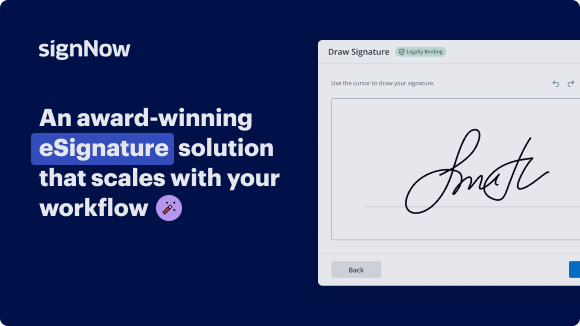

See airSlate SignNow eSignatures in action

Choose a better solution

Move your business forward with the airSlate SignNow eSignature solution

Add your legally binding signature

Integrate via API

Send conditional documents

Share documents via an invite link

Save time with reusable templates

Improve team collaboration

Our user reviews speak for themselves

airSlate SignNow solutions for better efficiency

Why choose airSlate SignNow

-

Free 7-day trial. Choose the plan you need and try it risk-free.

-

Honest pricing for full-featured plans. airSlate SignNow offers subscription plans with no overages or hidden fees at renewal.

-

Enterprise-grade security. airSlate SignNow helps you comply with global security standards.

Bill book sample in word format for Life Sciences

Creating a bill book sample in word format tailored for the Life Sciences sector requires precision and a user-friendly process. Leveraging airSlate SignNow can streamline document management, allowing businesses to draft, sign, and send important documents efficiently.

Bill book sample in word format for Life Sciences

- Open your web browser and navigate to the airSlate SignNow homepage.

- Register for a complimentary trial or log into your existing account.

- Select and upload the document you wish to sign or need other parties to sign.

- If you plan to use the document again, create a reusable template.

- Access your document and customize it by adding fillable fields or necessary information.

- Affix your signature and designate signature fields for recipients to sign.

- Proceed by clicking Continue to configure and send an eSignature invitation.

Utilizing airSlate SignNow benefits businesses signNowly. It provides a robust return on investment by offering a comprehensive feature set while remaining budget-friendly. Its user-friendly interface is specifically designed for small to mid-market businesses, ensuring scalability without unnecessary complexities.

With transparent pricing that excludes hidden fees and superior 24/7 customer support for all subscription plans, airSlate SignNow stands out in its category. Start your journey towards superior document management by signing up for a free trial today!

How it works

Get legally-binding signatures now!

FAQs

-

What is a bill book sample in word format for life sciences?

A bill book sample in word format for life sciences is a template that allows professionals in the life sciences sector to create detailed invoices and billing records. This format is designed to facilitate easy descriptions of services and products while ensuring compliance with industry standards. Using such a template can help streamline billing processes in laboratories, clinics, and research facilities. -

How can I obtain a bill book sample in word format for life sciences?

You can easily download a bill book sample in word format for life sciences from our website. We offer various templates that cater to the specific needs of businesses in the life sciences field. Simply navigate to our template section, and select the one that best fits your business requirements. -

What features should I look for in a bill book sample in word format for life sciences?

When searching for a bill book sample in word format for life sciences, consider templates that include customizable fields, compliance checklists, and easy-to-read layouts. Additionally, look for samples that allow you to insert your branding elements, such as logos and colors. This ensures that the final product reflects your company's professionalism and specific needs. -

Is the bill book sample in word format for life sciences easy to customize?

Yes, the bill book sample in word format for life sciences is designed for easy customization. Users can quickly edit text, adjust formats, and add or remove sections as needed. With intuitive editing tools in Microsoft Word, you can personalize your bill book to match your brand and operational requirements. -

Are there any pricing options available for the bill book sample in word format for life sciences?

The bill book sample in word format for life sciences is often available for free or at a low cost, depending on the provider. AirSlate SignNow prioritizes cost-effectiveness, ensuring you have access to essential tools without a hefty price tag. Additional premium features may incur costs, but basic templates are designed to be accessible. -

Can the bill book sample in word format for life sciences be integrated with other software?

Many bill book samples in word format for life sciences can be integrated with various software solutions, especially if you use compatible invoicing tools. AirSlate SignNow offers seamless integration options that allow for easy eSignature capabilities. This ensures your billing process is both efficient and compliant with industry regulations. -

What are the benefits of using a bill book sample in word format for life sciences?

The primary benefits of using a bill book sample in word format for life sciences include improved accuracy, time savings, and professional presentation. A well-structured template enhances clarity in billing while reducing errors. Furthermore, it allows businesses to maintain a consistent and professional image in their financial communications.

What active users are saying — bill book sample in word format for life sciences

Get more for bill book sample in word format for life sciences

- Invoice Simple Estimate Maker for Teams

- Invoice simple estimate maker for organizations

- Invoice Simple Estimate Maker for NPOs

- Invoice simple estimate maker for non-profit organizations

- Tax Invoice Template Word for Businesses

- Tax invoice template word for corporations

- Tax Invoice Template Word for Enterprises

- Tax invoice template word for small businesses