Force Byline Order with airSlate SignNow

Get the robust eSignature features you need from the solution you trust

Choose the pro service created for pros

Configure eSignature API with ease

Work better together

Force byline order, within minutes

Reduce your closing time

Maintain important information safe

See airSlate SignNow eSignatures in action

airSlate SignNow solutions for better efficiency

Our user reviews speak for themselves

Why choose airSlate SignNow

-

Free 7-day trial. Choose the plan you need and try it risk-free.

-

Honest pricing for full-featured plans. airSlate SignNow offers subscription plans with no overages or hidden fees at renewal.

-

Enterprise-grade security. airSlate SignNow helps you comply with global security standards.

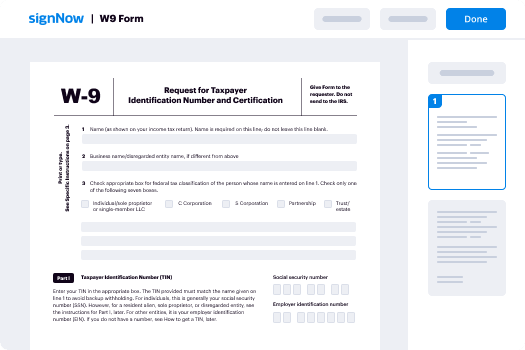

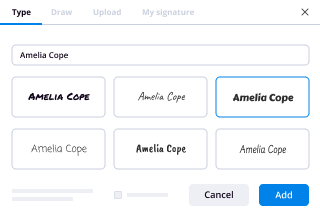

Your step-by-step guide — force byline order

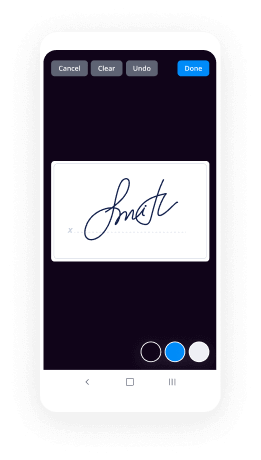

Leveraging airSlate SignNow’s electronic signature any business can accelerate signature workflows and eSign in real-time, delivering a greater experience to customers and workers. force byline order in a few simple steps. Our handheld mobile apps make working on the move possible, even while off the internet! eSign documents from any place worldwide and make deals faster.

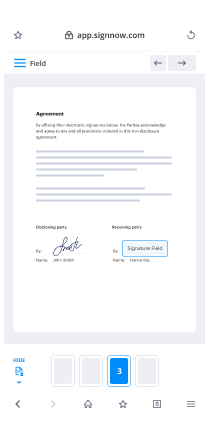

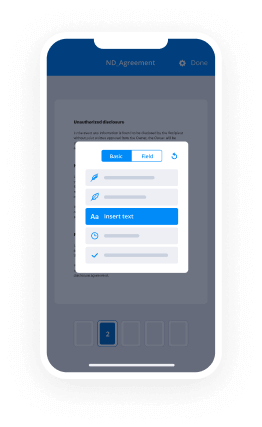

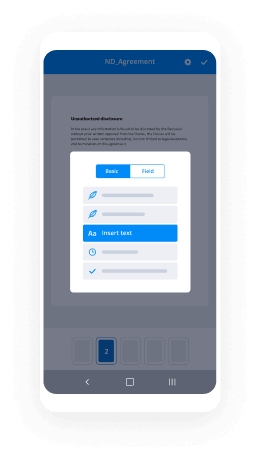

Follow the stepwise guide to force byline order:

- Log in to your airSlate SignNow account.

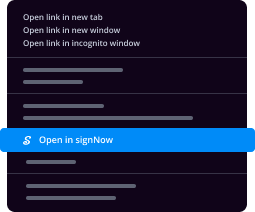

- Locate your needed form within your folders or upload a new one.

- the template and make edits using the Tools menu.

- Drag & drop fillable fields, type textual content and eSign it.

- List several signers via emails and set up the signing sequence.

- Choose which individuals can get an completed copy.

- Use Advanced Options to reduce access to the record and set up an expiry date.

- Click Save and Close when finished.

Furthermore, there are more enhanced tools accessible to force byline order. Include users to your collaborative digital workplace, view teams, and track collaboration. Numerous consumers all over the US and Europe concur that a solution that brings everything together in one holistic enviroment, is the thing that enterprises need to keep workflows performing easily. The airSlate SignNow REST API allows you to integrate eSignatures into your application, internet site, CRM or cloud storage. Try out airSlate SignNow and get faster, easier and overall more productive eSignature workflows!

How it works

airSlate SignNow features that users love

See exceptional results force byline order with airSlate SignNow

Get legally-binding signatures now!

FAQs

-

What is a byline in a newssignNow example?

A byline is just a line giving the name of the reporter or writer of the news story. \u201cPolice hunting for the killer of a police officer stabbed in her home in northwest London are seeking a man in a hooded top seen running away from the scene by neighbours, writes John Smith, Crime Desk.\u201d -

What is a byline in a feature article?

A byline is simply wording that gives credit to the writer of a news story, article, or blog. It is typically found in an article between the headline and first line of the article body. The byline started out as a method for accountability and credit, but in time it so much more. -

How do you do a byline?

Byline articles are an excellent way to retain ownership of key messages and establish thought leadership. ... Consider your audience. ... Don't self-promote. ... Develop a strong thesis. ... Construct an outline. ... Use subheadings. ... Include quality data. ... Don't be boring. -

What should a byline look like?

Bylines in NewssignNows and Other Publications Bylines on airSlate SignNow usually appear after the headline or subhead of an article but before the dateline or body copy. It's almost always prefaced by the word "by" or some other wording that indicates that the piece of information is the name of the author. -

Why is a byline?

A byline is simply wording that gives credit to the writer of a news story, article, or blog. It is typically found in an article between the headline and first line of the article body. The byline started out as a method for accountability and credit, but in time it so much more. -

What is a byline in an essay?

A byline is a short paragraph that tells readers a little bit about the author and how to contact the author or read additional content by the author. In most online content, the author bio can be seen at the end of the article. -

What is a byline in a book?

Definition of byline. (Entry 1 of 2) 1 : a secondary line : sideline. 2 : a line at the beginning of a news story, magazine article, or book giving the writer's name. byline. -

How do you find the author order?

Authorship order In many disciplines, the author order indicates the magnitude of contribution, with the first author adding the most value and the last author representing the most senior, predominantly supervisory role. -

What is a byline PR?

Contributed articles bylined by a key executive are part of any PR program that emphasizes thought leadership. Bylined content helps establish a B2B executive as an industry expert or brand voice, and it's also a strong way to boost SEO for an individual or company.

What active users are saying — force byline order

Related searches to force byline order with airSlate airSlate SignNow

Force byline order

Today's episode of Hidden Forces is made possible by listeners like you. For more information about this week's episode or for easy access to related programming, visit our website at hiddenforces.io and subscribe to our free email list. If you listen to the show on your Apple Podcast app, remember, you can give us a review. Each review helps more people find the show, and join our amazing community. And with that, please enjoy this week's episode. What's up everybody? My guest on this episode of Hidden Forces is Tom Burgis. Tom is an investigations correspondent at the Financial Times. And he's also the author of Kleptopia, which is a book that chronicles the world of dirty money with its complex web of criminals, money launderers, and politicians who enable it. The reason that I wanted to have Tom on, and why I think this conversation is important is that it seems to me that what we've been seeing in recent decades is not only a rise in corruption, but really, the rise of a new international kleptocracy. A kleptocracy that knows no boundaries, that plays by a completely different set of rules, and which is enabled by a sort of political consensus to loot. And this looting has become so pervasive that the money extracted by these individuals and their corporations and front companies is enough to buy the political power, to stack the legislatures, to change the laws, to loot some more in a self-perpetuating cycle of fraud, criminality, and widespread exploitation of the public. And ultimately, the very system of liberal democratic capitalism upon which even those doing the looting depend for their survival. Unfortunately, the conduits through which we learn about this phenomenon are themselves often held captive to one degree or another by these same forces. And I'm not quite sure what the solution is. But I'm confident that the more obvious this becomes to the public, and the more our elected officials choose to ignore it, or attempt to divert our attention away from it, the more radicalized the electorate is going to become, and the more susceptible we are going to become to the promises of candidates who will seek to fill the vacuum of trust left by our politicians with power. Now, a quick note, to those of you who are new to this podcast, we don't accept commercial sponsors. These conversations last anywhere between 90 minutes to two hours, the second half of which is made available to our premium subscribers along with transcripts to each conversation as well as notes in the form of rundowns that I put together ahead of each and every episode. If you value what we do, consider signing up for one of our five content tiers. If that's not an option for you, there are still things you can do to support the show by sharing your enthusiasm and love for the podcast. Tweet it out, send it to your friends, and write us a review on Apple Podcasts. Your support of the show is what keeps me going. That and some really, really great conversations. And on that note, please enjoy this week's conversation with my guest, Tom Burgis. Tom Burgis, welcome to Hidden Forces. It's an absolute pleasure to be here. The pleasure is all mine, Tom. So, for our listeners who may have never read any of your columns on the FT. Many will, perhaps some will have read them without knowing it was you, but now they do. Give us a sense of your background. I'm really fascinated when I get to speak with investigative journalists because it's one of those things where it almost feels like a dying breed, although there's been a bit of a resurrection in the field in recent years. How did you get into this business? Well, I am a failed poet. I come from Manchester, North of England. I studied in London, studied literature, and then did a bit of manual labor for a while to make some money to go off to South America with a friend to wander around jotting my incredibly pretentious poems in a notebook, and then winding up in Santiago de Chile where the local- A great place to write poetry. Sorry. A great place to write poetry. Yeah, absolutely, Neruda's city, and I got... I decided I wanted to stay, and I got a job on the Santiago Times, which was a fantastic newspaper, the only English language newspaper in Chile. Quite a small readership but devoted, and staffed by an extraordinary collection of people. And for an exchange for being allowed to live in their shed, I became the arts editor, which is grander than it sounded. I basically tried to cobble together some cultural coverage, and put it in the paper, and still on it on the side write these... Work on these poems, a couple of which were published in the most obscure journals imaginable. Anyway, while I was living in Chile, this is 2004 I arrived. And then it was a time when Chile was starting to have its reckoning with its dictatorship. Augusto Pinochet had not been extradited from London to Spain. He'd said he had a medical condition that meant he needed to go back to Chile, and the Blair government in the UK had gone along with that. And what was happening in Chile was that as time was passing since the end of the dictatorship, fear was ebbing away. And people were starting to push to have a reckoning with long decades of military rule, and all the atrocities that went with that. And I was on the Santiago Times. I had a bit of Spanish that was ropey, but improving and I happened to be there when there was a couple of other brilliant journalists. And we started trying to cover this. Trying to cover the seismic moment when Chile had its reckoning. And we started to look more broadly about how actually the way Chile had been plugged into the global economy was benefiting the rich, and those who had supported Pinochet and screwing over quite a lot of the rest of the population. And it was this extraordinary thing to witness. And in those few months, I pretty much abandoned my fledgling and doomed poetry career and just by mistake became a news reporter and started writing about what was going on for the Santiago Times, but also for a couple of papers back in the UK. And then I had to leave after about a year and come home for a family reason. And then by then I'd thought to myself, "Well, what is the sharp end of where global economic power really transforms people's lives, and in some cases shatters people's lives." And that happens in Africa. So, I spent a little while trying to wrangle a foreign posting in African and eventually I got one for the Financial Times. I went to Johannesburg, covered Southern Africa, covered the fall of Thabo Mbeki and the rise of Jacob Zuma. Covered the Zimbabwean elections, and then I moved to West Africa and Lagos astounding, astonishing city of 20 million people. And that sort of beating heart of a lot of what certainly that region and Africa more broadly, but also the epicenter of oil based corruption in Africa, and this extraordinary confluence of extreme wealth, and absolute grinding poverty. Then I wrote a book about that. After coming home for a while following... I got a bit messed up by covering a lot of violence in Central Nigeria. It took me a while to get over that, and then pieced it together- You mean physical violence? Yeah, yeah. Well, I saw quite a lot of grim stuff. But there was one particular massacre in a city called Jos in Central Nigeria in January 2010 that I got to this village, me and a couple of others just not long after the inhabitants had been slaughtered in various ways, and burned, and so on. And it took me a long time to get over that, and I eventually went under with PTSD and depression and so on. Part of the way I came out of that hole was to write The Looting Machine, which is this book, my first book traveling back across large parts of Africa trying to understand how the global oil and mining industries, which are the only bits of the global economy that really have anything to do with Africa. How they ferment corruption, and how that corruption leads to a political system that is ultimately based on violence of the kind I'd struggle to compute. So, I wrote that book. And then since then, since that time I've been on the investigations team of the Financial Times in London, but traveling all over the place, and have expanded those inquiries from Africa globally to these questions of how corruption is reshaping the world. That's obviously taken me to places like the former Soviet Union, but obviously Hong Kong, and looking at South America sometimes as well, and also how the big Western money capitals are the engines of this kleptocracy. So, that's how I got here. Maybe we can revisit that a bit. That personal byline in the overtime because I think there's some interesting stories. I mean, I'm fascinated by that experience, and especially what keeps you going. What really motivates you to continue to do what is a very difficult job, and one that obviously can be pretty dark. But we'll see if we revisit that in the overtime. I read Kleptopia. It is such an unusual book in terms of the types of books that I usually read because it is strongly narrative. Although in that sense, it's similar to books like Joshua Yaffa's Between Two Fires, which covers some of these themes through the stories of people striving to succeed in their lives and careers in post-Soviet Russia. And that's another interesting aspect of a book, which is that Russia, and post-Soviet Russia is sort of very center in the book. And it often seems to be in anything that I read regarding kleptocracy, disinformation, sort of global mafia. And maybe that's something to ask you about there. But how would you describe for listeners who haven't read Kleptopia, how would you describe the book and what it's about? It's about the rise of a transnational kleptocracy. So, what do I mean by that? Kleptocracy is a place that's run through corruption. It's not run through consent. It's not run through the rulers of that place appealing for the consent of the people one way or another. It's run by people who hold power, more or less illegitimately, and use it to enrich themselves, as opposed to try to advance the common good. Now, that tension exists everywhere. One of the things I really found in Africa, one of the reasons I wanted to write my previous book, The Looting Machine was that there is this pervasive idea that corruption is somehow cultural. It's often a sort of soft racism to that, that corruption is yes, cultural, and is linked to certain people's and certain ways of being. It's complete rubbish, obviously. If you put anyone in a position where they can enrich themselves and their families, and there won't be any sanction for that. People will do that. Practically, everybody would do that in democracies anywhere. That's why we give ourselves institutions that prevent conflict of interest. It's to prevent, it's to spare us this temptation. But what you start to see I think is while we spend a lot of time thinking that corruption is an aberration, especially in the West, we spent a lot of time thinking that. But if you spend much time in, say, Nigeria, or Russia, or whatever, you quite quickly realize that that's a mistake. That corruption is the center of how power works. And if you look at your map, and you look from, let's say, Budapest to Beijing. And then you look from maybe Ankara down to Pretoria. And then you cast an eye up and down the whole of the Americas, you'll see that most places fundamentally today run on corruption. That's how power is wielded, and Kleptopia is a distinct idea because those kleptocracy are uniting. So, they've always been kleptocracies, and there always will be. But they used to be more isolated. So, during the Cold War, you'd have client kleptocrats of the superpowers in the Philippines, or in Congo Zaire as was or wherever it may be. Pinochet, I think would probably count as one of those. So, they were international in that sense that they were linked into the superpowers. But what's emerged since the fall of the Soviet Union is the double trend of the spread of kleptocracy, and the acceleration of globalization, and those two things fusing. So, for instance, let me give you one example that's from the book. One of the most... It took some real digging to piece together this stuff by other journalists as well, I should add, but one of the most, I think striking stories in the book is the tale of how Robert Mugabe stayed in power so long and twice in two elections. He was able to tap this global network of kleptocratic powers. So, in 2008, to give you a potted version he stays in power when he's at the brink of being removed by his own people. He manages to bring 100 million dollars with the help of some guys from Wall Street, a London listed company and a kind of rally driving wheeler dealer of why Zimbabwe has been involved in the pillage of Congo for a long time, a former England cricketer. And these guys do their deal. They bring 100 million dollars, and then the people who have brought in that money, they cash out their side of the deal by selling on a platinum mine, and ultimately flogging a company to some Central Asian oligarchs with connections to the KGB, and to various dictators from the former Soviet Union. So, you can see in that flavor, that's one election in one kleptocracy, and the way this network kicks in will align interests to support one of its own. And then, five years later, by Mugabe taps somewhere else. A Chinese guy with seven different aliases connected to the Chinese military intelligence establishment who does a deal for diamonds and sustains Mugabe with some secretive money that he can use for another campaign of fear to extend his rule. So, Kleptopia is the place where these international networks of kleptocrats unite to cement their own power, and to steamroll over democratic institutions that might try to stop them. Now, so many questions there to discuss. I mean, you brought up Russia. I would love to understand why we've seen an acceleration in this kind of global kleptocracy since the fall of the Soviet Union. It seems as though like huge pockets that were once unavailable, the international capital, have now become available for plunder. And so, kleptocrats within those systems are able to tap that market for money, and then able to use that money to buy power, which allows them to remain in power. And then to use the international judicial systems to pursue people from within their countries. I'd love for you to answer that. But I want to also revisit something you suggested about I think public perception dealing with kleptocracy and corruption. One is, what is the distinction between the two, between corruption and kleptocracy? And how accurate is the public's conception of that distinction, and also how it operates within their own western democratic societies? Lots of fascinating questions there. Maybe I can just go to that one about the difference between kleptocracy and corruption. So, corruption is me calling up my kid's school teacher, and saying, "I really need her grades to go up a bit. If I just quietly buy you a plane ticket on holiday," maybe not at the moment, maybe something will local. But if I give you some inducement or some advantage. If I send a few bottles of wine around to your house or something like that, can you inflate her grade? So, corruption is very simply the abuse of a public office. Public corruption, I'm talking about, the abuse of a public office for private gain. So, there's corruption. Kleptocracy is when corruption becomes the system. I mean, it's as simple as that, I'd say. That makes sense. And I think that's actually what we've seen in post-Soviet Russia. I think most people when they think about illicit funds, and laundered money they think about them as totally illegitimate, and illegitimate businesses that mostly legitimate people wouldn't want to be caught dead associated with. But one of the things that comes across in reading your book, and in some other books that I've read dealing with the subject is that quite the opposite, the further up you go in the pyramid of power, the more difficult it becomes to differentiate between what is or is not legitimate activity. Because even if you don't engage directly in criminal activity, you still might be taking money or your campaign might be taking money from people with dubious political connections, or you might be a mid-level employee at a bank which launders billions of dollars a year in drug money on which your salary depends. In other words, how do we wrap our arms around a system that is so suddenly pervasive that it compromises people who wouldn't even consider themselves as being part of that system? I think in a way, there's always a danger with this stuff of over complicating it for ourselves. And in fact, I think that is the trap. So, all the front companies, and the Swiss bank accounts, and the anonymously held trust. Even this vocabulary I'm using now is designed to divert. That's its purpose. I think you're right. As you get higher up the chain of command in kleptocracies, and that's global. That's transnational. So, that can include a lobbyist in Washington just as much as it can include a dictator's daughter in Central Asia. As you get higher up, the more powerful, and the more potent the collective suspension of disbelief. So, someone like Tony Blair I write about in the book is a good example. So, one of the most harrowing things I did for the book was I went... I made it to a place in Kazakhstan called Zhanaozen and they don't like journalists to be there, but I got there. Others have got there too. But I think I've done some very detailed reporting of what happened there in 2011 when there was a strike by all workers, and the response of the security forces was to open fire, and then to torture the survivors in the most horrendous ways. To dock to the public record. So, to do two things. One, to absolve the security forces themselves of any responsibility, and to say that the victims had been the perpetrators of violence and the provocateur, whereas in fact, the opposite was true. And the second thing that this torture campaign did, and that combined with a sort of absolutely farcical kangaroo court trial that followed, administered over by a heavily perspiring judge in a courtroom by the Caspian Sea. The second thing this did was to falsely implicate one of the main political enemies of the dictator and exiled oligarch in responsibility for this, for stirring up this violence. And then what happened was that the dictator, Nursultan Nazarbayev, well documented to have vastly enriched himself at his people's expense. He was coming to Cambridge in the UK, the Mecca of rationality, and reason, and truthful inquiry. Not that I went there, but I think that's a fair description of it. And he needed to make a speech shortly after this horrific massacre. Now, he turned to someone who had been working as a consultant in Kazakhstan, and who's one of our times greatest communicators, Tony Blair, elected three times as the Labour Prime Minister of the UK. And now fabulously rich consultant in his own right. And Blair wrote a letter to Nazarbayev that I have in the book, essentially telling him, this is how to frame what happened in Zhanaozen for the polite consumption of the Western media. That part was really... It was kind of jaw dropping, to be honest. Well, this is where we get to this point about suspension of disbelief. So, does anybody in Russia actually believe that Putin hasn't stolen an enormous fortune? Does anybody believe this about half the leaders in Africa, or South America? Does anybody believe that Donald Trump isn't improperly enriching himself by continuing to own Mar-a-Lago and his Washington hotel? No, of course not. Any right minded person would see all this as corruption. But of course, that's not how political establishments can operate. They need an alternative reality. I don't think it's a coincidence. In fact, I think it's quite the opposite that this time we're in have alternative facts, as Kellyanne Conway said. This time we're in of the destabilization of truth, it is directly linked for me to the rise of kleptocracy because what kleptocracy needs to function is a kind of cognitive dissonance where those who benefit from corruption can sustain with a more or less straight face, a narrative that their power is legitimate, because without that, the whole thing unravels quite quickly. And you can do that in Kazakhstan by torturing people, and turning off the internet. It's much harder to do it in the West, but it's much more valuable to do in the West. Because if you can secure a narrative of your own legitimacy in the West, and you're the dictator of Congo, or Kazakhstan, or wherever it may be, then that is much more powerful to sustaining your rule. Because ultimately, the transnational kleptocracy, it's a quick three step process. Steal money, move it abroad, so it can be parked safely, and it can buy you legitimacy, then reflect that legitimacy from the West back home to keep you in power, sustain your immunity from prosecution, and allow you to go on stealing. And it's when that money arrives in the West, that again, and again, it seeks the experts in maintaining this jewel reality where you can live the pretense of your legitimacy. Rather like being a reality TV star on let's say, The Apprentice, while also at home maintaining control through, A, violence, and B tribalism. That's how it works. So, there's so many things that you mentioned that I want to dig into like about buying legitimacy, and sort of the PR function, the important role of public relations in all of this. Also, the increasing lack of credibility among the political class, and how I feel that that makes it easier to operate this type of kleptocracy. I mean, like I said, the story of Tony Blair, I interrupted you, and you didn't finish it, but basically you were making the point that he was advising Nazarbayev, the head of Kazakhstan on how to manage what was a horrific action directed by him and his state. And Tony Blair was Prime Minister of the UK, not at the time, but he was. And he had been elected into power by the electorate. So, this creates a cognitive dissonance, I think, and it's part of it. And we'll get into those things, but maybe would actually help for people to understand the process by which money is laundered. So, if I wanted to launder money today, how difficult is it to do? How would I go about doing that? It's tends to be easier the more you have. So, at the top level, you can use your connections, let's say in the 1990s to powerful spies, powerful politicians, and so on, to improperly secure through opaque privatizations, let's say, the rights to a huge mine in the former Soviet Union that by rights belongs to the Commonwealth, belongs to the collective. And then you can have your bankers at the Wall Street banks, and the City of London boutiques dress up this company as a corporation. You can list it in London. Pension funds will buy shares in it, and suddenly you've taken the proceeds of kleptocracy, and you've made it look like a shiny multinational corporation with a big thick annual booklet extolling its virtues. But I think you're asking about just a simple process of if you've got some... If someone's going to send you some money that they shouldn't be. And so, I'll talk for a second just about the actual nuggets in the process. But it's also important after that to talk about the deeper meaning of this. So, the nuggets in the process is basically there are three steps, placement, layering, integration. So, let's say that you Demetri are the prime minister's son. I'm going to call you the prime... It's going to make this British, that you're the prime minister's son, and the Prime Minister is about to decide whether the do good mining company will be given mining rights. And you are going to lobby the prime minister to give do good mining those rights, and they're going to secretly pay you to do that. So, that would, obviously, could be a crime. That would be corrupt. That would be paying a relative of a public official to abuse his office for private gain. So, how would you actually go about doing that? The first thing, the key to all of this stuff, the getaway vehicle of the global kleptocracy is the front company, or sometimes called the shell vehicle, there's all sorts of different flavors of this. And that you can get different ones, typically in different parts of the former British Empire, the Cayman Islands, British Virgin Islands, and so on. You can get some good ones in Delaware. You can get them in the Seychelles. You can get them in Hong Kong, Singapore. You can get them in Liechtenstein. You can get them all over the place. So, you would set up your front company, let's say in the Cayman Islands. So, you'd have your private banker do that for you. Now, that company is just called eggshell incorporated. Likewise, do good mining are not going to put in their books $100,000 bribe. They are going to find a way to disguise this to allow people who come across this payment in the future who might stumble across it to suspend their disbelief. That's what's always required, plausible deniability. So, what they might do is, let's say a simple way of doing it would be that they would set up a front company themselves somewhere else in the Seychelles. And that company would purport to be a marketing company. And they would drop a contract, but whereby do good sends $100,000 for marketing services to this company in the Seychelles. Now, once it's in there, that Seychelles company, that's a black box. It doesn't have to publish accounts, nobody knows where its money goes. So, the Seychelles company can then send the 100 grand to your front company that you've got in the British Virgin Islands. So, there we are. So, this is, obviously, I guess more complicated than this. And you can put layer upon layer upon layer of difficulty. But this is the basic structure. So, you've got your 100 grand. You have a quiet word with your dad, the prime minister. He gives the rights to do good mining, everyone's happy, except you so far because you've got your 100 grand, but it's sitting in the, let's say, Swiss bank account that's been opened in the name of eggshell incorporated your company in the British Virgin Islands. So that's all well and good, but you've got to be able to use it. And especially these days, it is a bit harder. It's still relatively straightforward. It's still largely farcically straightforward, but it is a little bit harder. Especially since 9/11 there'll be more checks on these things. And since Putin's revanchism really kicked in, there are more checks on dodgy money going through banks. So, bankers do occasionally have to try and make some effort to try and work out where the money is coming from. So, it's a bit harder for you these days just to, let's say, buy a big house in California, have it put in your name, but be paid for by eggshell incorporated. So, you might, let's say, put a lawyer in between. You might find your New York real estate lawyer. Well, what he would do is he would have his own offshore company that would buy the house. This is one we're doing it. They would buy the house you want to buy as your reward. Does he act as a referral agent in this case? Not necessarily, no. But it would just be someone to whom there is no public connection. So, probably what you do is you put this person, this lawyer's name would go on the deed. Your company, eggshell incorporated would pay the 100 grand that you're going to use to buy this house. Probably not enough for a house these days, I guess, but a big enough house for a man of your standing being the prime minister's son and take your cup, but let's say 100 grand will do. You put it into the lawyer's Escrow account, that is I believe covered by legal professional privilege. But even if it's not no one can then... No one has a right to look into that account. And there's nothing to show any connection with you. So, there's still no paper trail connecting you to this house. You've given the money to the lawyer in secret. The lawyer has bought the house. You can set up another offshore company, which will actually own the house. And somewhere in the vault of some registration agency in... I don't know, Nassau is a piece of paper. It's a power of attorney that says that these five dummy directors of your offshore company that owns the house they actually answer to you. You don't own anything. But you have a power of attorney that says that you control it. That's just one fairly typical setup. And that's even before you get to, let's say, moving money instead into the US instead to buy a house you get to moving it to say, a lobbyist who might be helping advance the interest of an adversary or whatever it might be. But that's the basics. But do you mind if I just go on to the second point now? No, please, please. Well, as I said earlier, and this is really brought home to me during the reporting on this book, which involves time and the killing fields of Eastern Congo. And, as I said, trying to piece together what happened in that massacre in Kazakhstan, and going to interview one of the biggest mafia bosses in Moscow. And looking into the suspicious deaths of witnesses in a corruption case, witnesses who died, I might add, not in Kazakhstan, or in Congo, but in Missouri. The most important thing that dawned on me, again and again, is how money moves between people. As a matter of time, farcically over simplistic, but what is money? I come back to this wonderful line in The Selfish Gene, Richard Dawkins' masterpiece. He says that money is a tool for delayed reciprocal altruism, by which he means it's a token for delayed reciprocal altruism. A token that lets societies of human beings cooperate in very large numbers among strangers. You can do altruistic things for your friends and family because you know them. But why on earth would you ever give a haircut to a stranger if you're a hairdresser? Or why on earth would you ever give a loaf of bread to a stranger? It's because they give you a token that says that they've done something for another stranger, and you exchange these tokens. I don't think that's oversimplistic. I think that's the most wonderfully straightforward, clear, evolutionary understanding of what money is. And that's how large societies cooperate. And it's that massive cooperation that is the definition of humanity. So, these tokens of reciprocal altruism are pretty important. Now, what's vital is that they do represent altruism, so that we can trust that, that money, that, that token has been earned by doing something that someone else in society found worthwhile, and therefore it has value. Now, we can only do that because we know who's holding the token. We can publicly see that the guy cashing in the token is the guy who gave the loaf of bread to the woman around the corner or is the guy who cut their kid's hair. Once money starts to be anonymous, it becomes impossible to verify this societal value. Now, we can get into if you want, there are arguments that people make in favor of being able to use money in secret, but we can come to those. I think they are massively outweighed by the damage that's done, and in fact, what kleptocracy is, it is the inversion of this process. So, it is Putin, Nazarbayev, Kabila in Congo. You could list a lot of them. Kim, in North Korea is a very good example. But sadly, there are more examples of countries that are run this way than countries that are not. It's an inversion of this principle of tokens, of altruistic tokens because the money that is acquired by doing the very opposite. It's acquired just as in the example we gave, it's acquired by abusing that public office, that trust the society has put in you to steward the collective interest by turning that on its head. And by selling that, essentially, for your own profit. And then this is where again, this is another way of understanding what money laundering is. It's to remove the stain from those tokens that you've illegitimately acquired, and make them look like tokens that you can spend in society. That you can buy houses with. That you can buy lobbyists with. That's the key, I believe, to understanding. And that's why I think we get so easily diverted in the nuts and bolts of front companies, and money laundering, and so on. But what we're actually talking about is this version of one of the most basic things that makes societies work. Yeah, so a few notable observations. One is that our financial system, and this was born out in the FinCEN files, for example, which I believe were over the course of about 20 years, roughly 200,000 suspicious financial transactions that occurred. And for the most part, even though they were flagged, nothing really happened. There was no action that was undertaken. And that was the case in point made by your story of Nigel Wilkins in the book. So, I'm sort of fascinated to understand why that is. And then another observation, and you hinted at it a few times, which is that in this world the past is your enemy, it needs to be altered. And so, there's this interesting intersection between people who are engaged in this kind of seedy underbelly of illicit gains and money laundering, and organized criminality, and the need to employ agents of disinformation. Cyber warfare, public relations, because truth is the enemy in this case. And so, this then intersects- Yeah, brilliantly put. Sorry to interrupt, but that's fantastically put. That's exactly it. Right. So, why don't you just take that and run with it? You can take that point, and we can tackle the other one later. Well, but I mean, I think Nigel Wilkins kind of embodies this in a way. I mean, Nigel Wilkins for people who haven't read the book. So, the beginnings really of his book or the book in the form it took is about five years ago, The Looting Machine, my Africa book had come out, and we did an event at the Frontline Club in London, which is a wonderful place. Like a war correspondents club where you can meet lots of extraordinary people. And we did an event about corruption and took questions, and a chap at the back in quite colorful shirt as I remember, balding, glasses, kind of heading towards retirement age. He put his hands up and he said... and gratifyingly it was quite full, but he got our attention, and he said, "Well, yes, interesting to hear you talk about all this corruption. I used to work for a Swiss bank, and there was certainly a lot of corruption going on there." I remember catching the eye of one of my editors who was in the audience, and thinking we better... We need to... Who the hell is this guy? So, anyway, we got talking to him afterwards at the bar of the Frontline and his name was Nigel Wilkins. And he explained how yes, he used to work at a Swiss bank, and he was quite cagey to begin with. But he was saying yes, there were certainly reasons to suspect that the financial secrecy that the banks were supplying to their clients, that his bank, that his colleagues, the Swiss bankers were supplying to their clients. It was certainly reason to believe that that secrecy was possibly being used for a nefarious purpose. So, Nigel and I arranged to have lunch, and we had lunch at the... There's a restaurant next to Shakespeare's Globe on the south bank of the Thames. Nigel and I few met a few times, and he'd have a different, one cocktail from the list, work his way through the list. And we'd talk a bit more, and he'd explain this to me. He hadn't really been a Swiss banker. He was an economist by trade, but he'd got this job at this Swiss bank's office. It was just around the corner from the Bank of England right in the heart of the city of London, which is in turn the heart of the global financial system, the aorta of our system. And Nigel got a job as this thing called the compliance officer, which is a relatively new job, which essentially means you got to try to make the bank at least look like it isn't just wantonly trafficking in tainted money and dirty money. So, Nigel Wilkins began to suspect that that's exactly what was going on in his bank. That financial secrecy was being used for nefarious purposes. And he was a mischievous soul with a distrust of authority, and a sort of delight in messing around with authority. So, he started to when all his colleagues would got out to champagne bars in the evening, he would just walk around, pick up what they left casually on their desks, photocopy it, and start to take it home, and he built up 1000 pages of secrets, and eventually he gave them to me. I wrote a story in the Financial Times that wasn't really very good. I'd only got a part of his story, and he'd only let me tell part of his story. But I also hadn't really followed the threads far enough. I also made the mistake of getting entangled in the detail, the detail that is meant to entangle you. And gradually, I won't give away what happens to Nigel, although he suffered for his courage. Gradually, I started to find the human beings, and I started to be able to get out to Congo and Kazakhstan and other places, and understand the human dynamics and the power dynamics behind what Nigel had stolen, essentially. And I guess that comes back to something we mentioned earlier about there being a narrative book. I think it's not kind of... There's a real reason why I've tried to write this book, so it reads like a novel. It's not purely stylistic, although I think, I would like to think it's a much better and more gripping and thrilling and enjoyable read as a result. But also because that is really the heart of this is to get to what a novelist does, which is to get to the human beings, and to the human minds, and to the psychology of people acting in the world, and to penetrate through the layers of financial secrecy that are meant to disguise human's wielding power. I would agree with that. I thought you did a masterful job with it, actually. You mentioned that you got caught up in the details. If you can't talk about what those were or that's fine, but what did you- No, no, no. I just didn't write a particular good story. I see. Okay. So, it wasn't because those threw you off from what the real story was? Well, kind of, yeah. I mean, it was, so when I worked on initially with Nigel was a story that ran in the Financial Times. It's called Dark Money, The City's... as in the City of London, the city's dirty secret, I think that's what it was called, and Nigel was in there pseudonymously as someone called Andrea, and it was a story about the tricks of financial secrecy. So, literally describing, you use this law firm in Panama, and you put it together with a front company from this place and that place. And in passing, it mentioned some of the names, but it was really, it just made a fundamental mistake that actually, I think a lot, sadly, of reporting in this area does, which is that it writes about the surface, which is what they want you to write about. That's why the surface is there to distract us. So, it was a decent effort. But for various twists of fate that followed that I won't... Let's not reveal the people who haven't read the book, but I was later able to write much more fully about Nigel, and also to spend the time really, really following the threads that came out of those red boxes of stolen documents that he had and to penetrate the surface, and to fine ultimately, at the end of it, what you find is the violence, that is kind of the corollary of corruption. If you rule through corruption, if you're rooting to enrich yourself, you have no hold. You have no claim to the consent of the people in whose name you rule. So, ultimately, you have to whip up tribal loyalty. And that's what I realized from long years thinking about that massacre in Nigeria, or you just buy people off. Sometimes you do both. But that's where the contract between rulers and ruled is inverted. And just the last point, you made a brilliant point about how the truth is the enemy. That was essentially what Nigel Wilkins was standing up for. In a world of financial bullshit, and the social media age where you are whatever you say you are. And he really, I think Nigel sort of foresaw the rise of a certain type of politician that was seeing gain a great deal of power in the UK, in the US and elsewhere, who did become detached from reality. Nigel was just in a stubborn, brilliant way. He's a brilliant man, just insisting that the past happened, and that there were certain sets of facts. Yeah, sure, open to interpretation, but a certain set of things happened. Certain sets of people move money between themselves, and that might justifiably be considered a conflict of interest. And there were people behind these front companies, and they have names, and they could be identified. And if they had done something wrong, they should make a public accounting of that. He just insisted on those things. That's why I'm so fond of Nigel, and that's why I wanted to make him the hero of the book. He could have been any one of us. He's an ordinary bloke. I think he would have said that quite proudly. But I think, yeah, that's the point of Nigel really in the book, anyway, apart from his wonderful nature is that he just in a bloody minded way said, "No, we are not going to adapt the past to suit the interests of the powerful and the present." What happened, happened, and it's still there somewhere if you just dig down to get it. One of the... Again, when you talk you say so many things that I want to pull. Sorry, man, I should be-- No, it's wonderful. I should be briefer. No. Please, no, actually, you're actually fantastic. One of the things that came up for me, again, with this point about legitimacy is not just about buying legitimacy in the West, but also the legitimizing power that comes with controlling a state because- Yeah. Yeah. And so we've obviously seen that in the case of Nazarbayev. And this brings me back to another connection that I had when I was listening to you talk about characters. The way that the financial crisis was discussed, the 2008 crisis was discussed in the United States for the most part by the media, it didn't focus in on the characters. That's what made the Big Short such a great book, it focused in on these different characters. Oh, yeah. And in so doing, it's sort of sanitizes what really is criminality at the highest levels of both government and the private sector. But when we look at some of these actors who have engaged in this type of criminality, and who have benefited from it, consciously, whether directly in a way that you can point to and say, "Ah, that's clearly stealing money." Or in an indirect way by enabling systems that allow you to enrich yourself at a corporate level. They've done this by the backing of the United States government and European governments. And the electorate saw that. The people saw that in 2008, and I think that that has wreaked tremendous damage on politics in the country. And very early on, you mentioned Donald Trump. You mean that, so it was the thing that's wreaked the damages the discrediting of the state, essentially? The discrediting of the state, and what that did to the electoral function, the logic function of the electorate, and how people think about what matters when they vote, and how much credibility to put in the words of the politicians that are running. And I think someone like Donald Trump, this is where I have a difficult time talking about politics because people get triggered, and it's kind of annoying, to be honest. I don't think people should get triggered. No, right. Just briefly, I would say that the crucial thing to understand about corruption is it's nonpartisan. Right. Exactly. A hundred percent. Yeah. Yeah. A hundred percent. And that actually speaks to my point, I think one of the appeals of Donald Trump, and why the arguments put forward by his detractors carry a lot less weight is because they want to pin it all on Donald Trump. They want to say, "Look at this man. He hasn't released his taxes. He doesn't pay taxes. He does all these business deals around the world with sketchy characters." And the public's like, "Wait a minute, sorry. Weren't you the same guys who looted the Treasury 10 years ago? Are you serious? At least this guy's openly corrupt? At least this guy doesn't pretend to care about us." I mean, it's this blatant hypocrisy and unwillingness to grapple with the reality of how widespread this type of criminality and corruption is. That's actually, I think, really a big part of the problem because it causes us to get stuck arguing about who's to blame rather than diagnosing and figuring out how to fix the problem. I'm curious, what do you think about that? Well, a lot of things. I think it's a brilliant point. I think there's two bits or maybe one. The ones about the discrediting of the state that happened during the financial crisis. And maybe the other is to do with how Donald Trump doesn't happen in a vacuum. And he's the product of something bigger, or he's certainly not... Maybe he's exceptional in some ways, but certainly not unique. So, I had a really interesting conversation the other day with someone who used to be an MI6, and who had served in some big, serious kleptocracies. And this person is terrified about how the Western democracies are wide open to corruption by kleptocratic powers. The way this person told the story was that the root of this... Now, I don't think it's necessarily the perfect time or place to get into a big argument about the merits of liberal economics, but there is a thread of history that you can follow going back to Thatcher and Reagan. And that to some extent, I think, demonized the state, and start a vogue for privatization, and the primacy of the market. And then from that flowed Clinton and Blair, and the third way, which was essentially to say for the left to make peace with the market. And the vote for privatization continued, and you'd get these explosions around the world, let's say, I think huge moments were when the attempted privatization of water in Tanzania and Bolivia, for instance. You'd get moments when there'd be explosions of resistance around the world where people would suddenly say, "Hang on a second. There are some things that are just simple public goods. And if you try to inject the profit motive into them, they will go wrong. And we won't have the basic things we need." And that's why you get the back... Similar thing applies to the backlash against Blackwater after those mercenaries shut up Baghdad. Again, people just saying, "Hang on a second, surely defense, but security is something that will just be messed up by the profit motive, and we need it to be stewarded even if it's inefficient and costly, stewarded on a public principle." And my contact who'd been an MI6. He argues that this has become completely pervasive. This idea that the profit principle trumps everything, and that the market can solve everything. And also that this idea is being abused. So, all those bankers who were not engaging in capitalism, they were engaging in- Larceny- ... the looting- Wholesale larceny and theft. Wholesale larceny. Yeah, yeah, first of their private institutions. And then by extension of the states that bailed them out. They relied on this narrative of the market to cover up what they were doing. But you can see how it lays the perfect red carpet for the kleptocrats who want to march into the rule of law states spinning a narrative of capitalism to say that we are capitalists. You're capitalists too. Let's all be capitalists together. And again, I stress I'm not trying to make a partisan argument or argument about capitalism versus socialism or anything like that. I'm just talking about the dominant narratives, the ideas by which we live and how they get hijacked. So, the idea of capitalism has essentially been hijacked by the kleptocrats who dress up money that's been stolen as money that is legitimate capital. And then Donald Trump is the most extraordinary episode in this story because he is born a rich man. Fritters well all that money because he's not a very talented businessman. And then around the turn of the century, two amazing things happen at once. One is the advent of reality television. And the other is the tidal wave of money. You've mentioned a couple of times, I think you've alluded to why it is that Russia is this kind of awe city of Kleptopia. It's very simple. It's because the end of the Cold War was, I think you could make a good argument that it was the greatest transfer of collectively earned wealth, the entire Soviet empire to private individuals. I would say they're certainly bigger than the bank bailouts, which many of us would put in that category. Well, just to interject and strengthen a point. And then please continue. The point about privatization. I think what we've seen is this, a very fundamentalist philosophy or ideology around privatization, that privatization in and of itself is good without emphasizing how wealth is privatized. And Russia's case in point, the Russians are aggrieved at how the wealth of the nation, national companies and resources were divvied up after the fall of the wall. And that has left a lasting stain on the country's politics. And it's left many people to wonder just how much better a system full of oligarchs and mafia dons is to what we had in the days of the Soviet Union. And that's not to say that an authoritarian communist kleptocracy like the USSR was any good. It's just to say that what we have now isn't exactly what we were promised. And so, you can't just talk about privatization without context, but please continue. I just wanted to make that point. Well, right, yeah, but it was also a lie, wasn't it? I mean, what they were promised was the market. This abstract idea that would allow people to get ahead, and the kind of like the American dream, essentially translated into Russian, that was never what was happening. Well, it also, that kind of market fundamentalism, it doesn't really... Again, to the point of, one of the main points of your book, which is the interchangeability of money and power. So, if you privatize all of these assets in this manner, and you allow the accumulation of wealth in the hands of just a few people or a small network of individuals, you've created a new government. And so, you're back to square one. Yes. Well, I'd say, I'd go actually a step further than that. I'd say you haven't created a new government, but you've created... What would be a better word? A new cabal or something. And that's international [crosstalk 00:54:08]- You've privatized... This is the key, I think, you've privatized power itself. So, power in the same way that you could privatize a health service. Well, I mean, in the US that's already the case. But you could privatize, let's say, the entire education system. And the people who came to own it would be able to make a profit from schools. You could... Eric Prince seems to suggest to just Donald Trump, you could privatize the military. You could privatize... We talked about privatizing water. You could privatize anything, but there comes a point where you've privatized everything including power itself. So, what power becomes is what it is in Nigeria, which is simply a system for competing to share the rent. By rent, I mean the economic rent. In a petro state that's pretty straightforward. Really, the only wealth that comes into Nigeria is the money people pay Nigeria to buy its oil. That specific pot in the middle. It's given to the country. We talked earlier about the presumption that countries are legitimate things, states. That big pot of oil sits in the middle, and politics is just a competition to get a share of that. That's when privatization of power itself is complete. And actually, ironically enough, that's when the idea of privatization starts to become quite reasonable again because you go full circle, as with all of these things. They're all just policy ideas. That are very few absolute right or wrongs. So, actually, in Nigeria, they have very good arguments for privatizing things like the power system because it's so utterly corrupted that it's collapsed. Nigeria is the biggest energy exporter in Africa. It's got 180 million people living there, and it has less power generating capacity than North Korea. And what you need to do, and what there have been attempts to do is privatize that. So, it moves out of the hands of the totally corrupted state. So, you can see how these arguments are fluid. But in Russia, as you say, what happened was entirely illegitimate. It wasn't the process of privatization in order to try to secure a common good in the sense that privatizing the power system in Nigeria would be a genuine good faith attempt to use a different system to replace a failing system, and actually give people electricity. What happened in the former Soviet Union was just essentially the massive land grab of enormous wealth by people who held power. Again, just turning power into money, and then you can turn it back into power again by exporting it, and paying for legitimacy. I feel we've got slightly off the- No, no, it's fine. We covered that a bit in our episode with Bill Browder, episode 30 something. And in preparing for that episode, I learned a lot about how the plunder actually operated, and how simple it was, really. And how important Western institutions and Western actors were in that process. One of the things that's really interesting about this because what you have in this type of a system is a global mafia. And when you acquire wealth in such a system, it isn't as secure as it is in Western states, which is exactly why they want to move that money into Western countries. But as the system grows, as this cancer spreads, Western institutions themselves become more kleptocratic. And so, no one is safe. And this is the thing that you increasingly see. So, I actually want to continue this aspect of the conversation Tom, into the overtime because again, this point about power and legitimacy, and also we talked about it a bit with Donald Trump. You hinted at it with respect to reality television and branding. And again, the PR and the privatization of intelligence services, and military companies like Blackwater. I think the first time I learned about Blackwater was when I read Scahill's book back in 2006, or 2007, whenever he published it. I remember back then just being stunned at the fact that we were contracting out military services of this sort that resulted in killings, in murders in foreign countries. I realized then just how wide the scope of private power was, but I think it's even greater today than it was then. You're obviously right. So, can I just... Yes, please. Yeah. And then we'll move it into the overtime. I think it's also the second half of what we were talking about before, and the complement to this, the other side of this to remember that's so important is, yes, private interests, private wealth to simplify it hugely has grown vastly in relation to collectively held wealth in the West. But so you look at the City of London lawyers or the Manhattan lawyers that your kleptocrats, and his or her allies will fund. They're fantastically well trained, phenomenally well paid, and well equipped. And that's one side of it. But the discrediting of the state, again, there's been another really nefarious consequence of this, which is like, no one's... I think not even the greatest zealot among the market fundamentalist would suggest privatizing the legal system because that is ultimately the most fundamental common good, public good. But there's an extent to which that is happening. Now, let me give you an example. In the UK, sort of higher stakes ongoing corruption investigation is into a company called ENRC. The investigation is into whether this company which is controlled by three Central Asian ex-Soviet oligarchs, whether this company after it listed in London. It was a collection of Kazakh mines, and then it floated in London. It became one of the richest most valuable companies in the UK. The investigation is into whether this company's officers, representatives paid bribes to buy the mines that the company acquired in Africa in some of the most... The places that have suffered most terribly from their natural wealth, especially Congo. Now, the oligarchs and the ENRC have fought a long time saying they've done absolutely nothing wrong, and lots of people are trying to stitch them up. But let's just look at how the two teams stack up. So, on the one side you have the oligarchs themselves who are worth collectively about $7 billion. So, that's more money than most countries. They have removed their company from the London Stock Exchange, and they've shifted it to Luxembourg. And they've hired many, many law firms in London, and elsewhere. Hogan Lovells is the main one at the moment. Now, one of the things they're doing is suing the Serious Fraud Office, which is the UK agency that prosecutes serious white collar crime, and corruption, and bribery, and fraud, and so on. They're suing them for one and a half times their annual budget. So, I think it's about $90 million. Now, the Serious Fraud Office budget I think it's about $50 million a year. So, that's up against the oligarchs $7 billion personal wealth, and you talk to people who work at the Serious Fraud Office. Now, it may be that the Serious Fraud Office may be that this will all shut down the Serious Fraud Office has acted improperly, and that these allegations have been manufactured. But if you just look at the team sheet, the Serious Fraud Office is able to pay a fraction of the wages that the big city firms pay. They have to go begging to the Home Secretary, the interior ministry for supplementary bits of budget to do big cases. They're consistently vilified when they screw something up. But no one will give them enough money to do anything properly. And they're dealing with the most difficult cases, and the cases that go to the heart of trying to protect the UK, the UK's democracy and rule of law from the most serious economic crimes, and corruption essentially from kleptocracy. Now, their job gets even harder because in this case, the ENRC's case, at least three potential witnesses have turned up dead in suspicious circumstances, two in the US, and one in South Africa. This has been a story I've worked on a great deal, and included some of the details of in the book, but I'm just trying to give you a flavor there of one of the reasons that the Serious Fraud Office budget is so crap is that, like everything else, they suffered from austerity after the financial crisis. So, enormous profits were made for a long time by those who benefit from the financial sector. And when it all went bust, the public sector bailed them out. Therefore, we had to cut funding for precisely the agencies that are supposed to police white collar crime, and so we go round again. And we're vulnerable in a different way. But I think that kind of discrediting of the state is having real effects in leaving us vulnerable to this kind of weaponized money from the big and increasingly insert assertive kleptocracies, which I should add, just as a [inaudible] would include China. Right. For sure. Well, I mean, we've seen a lot of that kind of selective starving of, and detoothing of regulatory institutions. It's quite convenient. I'm going to move the rest of this conversation, Tom, into the overtime. For anyone who is new to the program, Hidden Forces is listener supported. We don't accept advertisers or commercial sponsors. The entire show is funded from top to bottom by listeners like you. If you want to access this second part of my conversation with Tom, as well as the transcripts, and rundowns to this episode, and every other episode we've ever done on the podcast, head over to patreon.com/hiddenforces. There's also a link in the summary page to this episode with instructions on how to connect the overtime feed to your phone. So you can listen to these extra discussions just like you listen to the regular podcast. Tom, stick around. I'm very excited to continue this conversation with you into the overtime. Yeah, sure, man. Today's episode of Hidden Forces was recorded in New York City. For more information about this week's episode, or if you want easy access to related programming, visit our website at hiddenforces.io, and subscribe to our free email list. If you want access to overtime segments, episode transcripts, and show rundowns full of links, and detailed information related to each and every episode, check out our premium subscription available through the Hidden Forces website, or through our Patreon page at patreon.com/hiddenforces. Today's episode was produced by me and edited by Stylianos Nicolaou. For more episodes, you can check out our website at hiddenforces.io. Join the conversation at Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram at hiddenforcespod or send me an email. As always, thanks for listening. We'll see you next week.

Show moreFrequently asked questions

What is needed for an electronic signature?

What is the difference between an electronic signature and a digital signature?

How do I eSign and instantly email a PDF?

Get more for force byline order with airSlate SignNow

- Genuine electronic signature

- Prove electronically signed Price Quote Template

- Endorse digisign Electrical Services Agreement Template

- Authorize electronically sign Share Entrustment Agreement

- Anneal mark Vehicle Service Contract

- Justify esign Gym Membership Contract Template

- Try countersign Service Contract Template

- Add Management Agreement byline

- Send Job Quote Template esigning

- Fax Letter of Interest for Promotion digisign

- Seal Product Launch Press Release signature service

- Password Payment Agreement Template countersign

- Pass Non-Disclosure Agreement (NDA) sign

- Renew Portrait Photography Contract initials

- Test Business Plan Financial eSign

- Require Copyright License Agreement Template eSignature

- Comment spectator signatory

- Boost petitioner email signature

- Call for person signature

- Void Business Purchase Agreement template esign

- Adopt Trademark Assignment Agreement template signature block

- Vouch Travel Booking Request template signature service

- Establish North Carolina Bill of Sale template email signature

- Clear Home Repair Contract Template template signatory

- Complete Veterinary Surgical Consent template initials

- Force Commercial Invoice Template template electronically signed

- Permit Pregnancy Verification template byline

- Customize Release of Liability Form (Waiver of Liability) template esigning