Draw eSignature Word Later

Make the most out of your eSignature workflows with airSlate SignNow

Extensive suite of eSignature tools

Robust integration and API capabilities

Advanced security and compliance

Various collaboration tools

Enjoyable and stress-free signing experience

Extensive support

Keep your eSignature workflows on track

Our user reviews speak for themselves

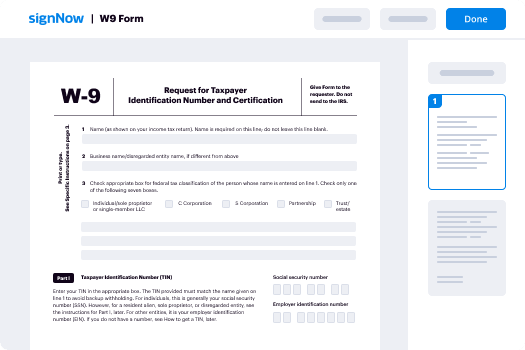

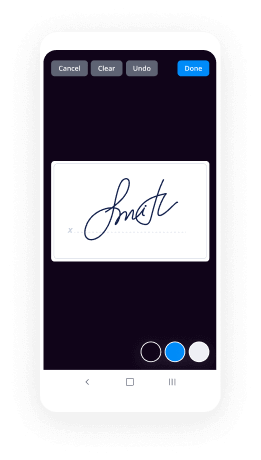

How to Create Your Signature in Word

Creating your signature in Word can improve the professionalism of your documents. With tools such as airSlate SignNow, you can effortlessly generate and incorporate your signature, facilitating a smooth and effective signing experience. This guide leads you through the straightforward steps to create your signature in Word using airSlate SignNow, while also showcasing the advantages of this robust tool.

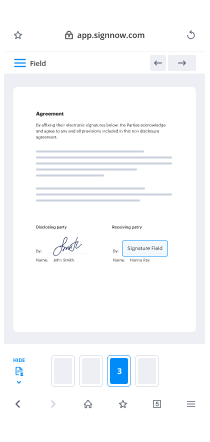

Steps to Create Your Signature in Word Using airSlate SignNow

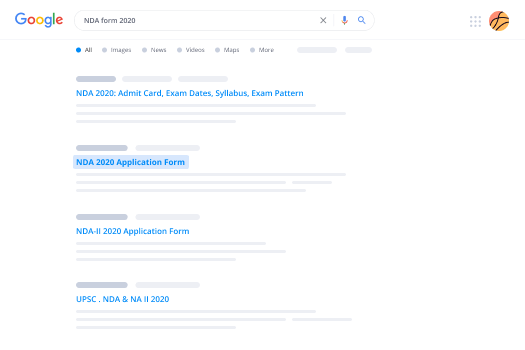

- Launch your web browser and go to the airSlate SignNow website.

- Register for a free trial account or log into your current account.

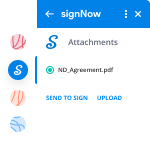

- Upload the document you want to sign or share for signatures.

- If you plan to use this document in the future, convert it into a template.

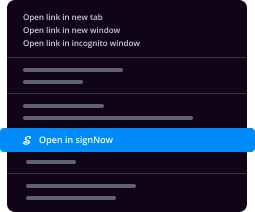

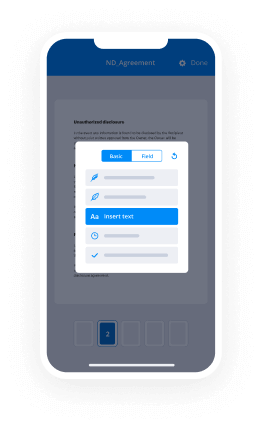

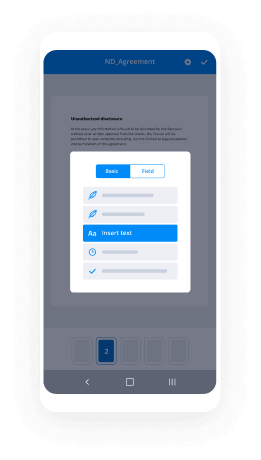

- Open the uploaded document and personalize it by adding fillable fields or other required information.

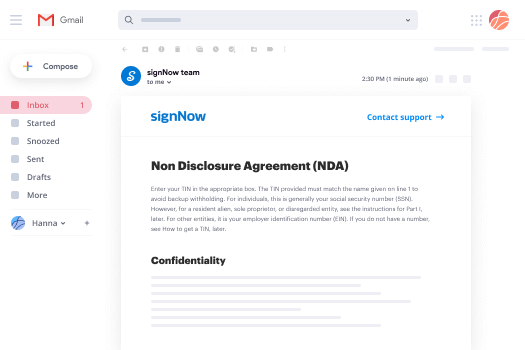

- Insert your signature and add signature fields for the recipients.

- Click on 'Continue' to complete and send out an eSignature invitation.

Using airSlate SignNow not only streamlines the process of creating your signature in Word, but it also offers numerous advantages for your business. With a comprehensive set of features at a reasonable cost, it ensures a signNow return on investment, making it ideal for small to medium-sized enterprises.

Discover the ease of airSlate SignNow today! Begin your free trial and revolutionize how you handle document signing, ensuring efficiency and professionalism in every agreement.

How it works

Rate your experience

-

Best ROI. Our customers achieve an average 7x ROI within the first six months.

-

Scales with your use cases. From SMBs to mid-market, airSlate SignNow delivers results for businesses of all sizes.

-

Intuitive UI and API. Sign and send documents from your apps in minutes.

A smarter way to work: —how to industry sign banking integrate

FAQs

-

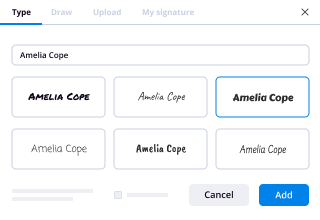

How can I draw my signature in Word using airSlate SignNow?

To draw your signature in Word, simply use the airSlate SignNow integration. This feature allows you to create and insert your custom signature directly into your Word documents, making eSigning a breeze. Just select the option to draw your signature, and you can easily customize it to match your unique style.

-

Is there a cost associated with drawing my signature in Word with airSlate SignNow?

airSlate SignNow offers a range of pricing plans, making it accessible for individuals and businesses alike. You can draw your signature in Word without worrying about high costs, as our plans are designed to be cost-effective. Check our pricing page for details on subscriptions and any free trials available.

-

What are the benefits of using airSlate SignNow to draw my signature in Word?

Using airSlate SignNow to draw your signature in Word offers numerous benefits, including convenience and efficiency. It simplifies the signing process by allowing you to create a personalized signature that can be easily inserted into any document. Additionally, it enhances the professional appearance of your documents.

-

Can I save my drawn signature for future use in airSlate SignNow?

Yes, airSlate SignNow allows you to save your drawn signature for future use. Once you create your signature, it can be stored in your account for easy access whenever you need to draw your signature in Word again. This saves you time and ensures consistency across all your signed documents.

-

Does airSlate SignNow integrate with other software for drawing signatures?

Yes, airSlate SignNow seamlessly integrates with various software, enhancing your ability to draw your signature in Word and other platforms. This includes popular applications like Google Drive, Microsoft Office, and more, allowing you to streamline your document management and eSigning process.

-

Is it easy to draw my signature in Word with airSlate SignNow?

Absolutely! airSlate SignNow is designed for user convenience, making it easy to draw your signature in Word. The intuitive interface allows you to quickly create and customize your signature, ensuring that even those with little technical expertise can use it without any difficulties.

-

What file formats can I use when drawing my signature in Word?

When you draw your signature in Word using airSlate SignNow, you can save it in various formats suitable for Word documents. Common formats include PNG and JPEG, ensuring compatibility and ease of use across different document types. This flexibility allows you to maintain high-quality visuals in your signed documents.

-

What are the best productivity tools for entrepreneurs?

I now accept Suggested Edits, as they come in. Include the price of the product/service.Pre Launch:Javelin. Start and grow your product faster. javelin.com/?ref=p5eybNFKResearch:Clipular http://www.clipular.com (free)Evernote http://www.evernote.com. Free, and $45 per year.Launching Soon Page:LaunchRock http://www.launchrock.comLaunchSoon http://launchsoon.comLanding PagesSelf Hosted:ThemeForest http://www.themeforest.net $8+Hosted:UnBounce (landing pages) http://www.unbounce.com $50/moKickOffLabs: http://www.kickofflabs.com/ $15/monthOptimizely: https://www.optimizely.com/ $17/monthTurnkey...

-

Which tools help to boost work productivity?

First things first, from all the tools I use, I’m listing a few that save me an immense amount of time. Thus helping me focus on things that matter. Here goes my list:Pocket - A handy tool to save useful links. After a while, my bookmarks are just unorganised and Pocket made it simple to save links. I could save everything in one place and hence retrieval is easy. Also, If I ever come across something during work that might be a distraction, I Pocket it and read it later.Buffer - Primarily I use this to manage posts and content from our SM handles. I schedule posts at one time and never have to look at it again. This saves a lot of time as I can dedicatedly work on the content and push them to the pipeline.LearnBee - (Disclaimer: my team built it and I use it every day). I use it to find a specific work file quickly or to attach multiple work files in an email or to search for a file to show to the team during a meeting. The Chrome extension just saves me an immense amount of time, which I otherwise waste searching for a file.Jira and Trello - Both of these tools help me individually as well as my team to prioritize, organise and complete tasks in a better and efficient way.

-

What are the best electronic signature (e-signature) solutions on the market, in your opinion?

[full disclosure: I’m VP Digital Transformation at Solutions Notarius Inc., a company that supplies electronic and digital signature solutions]It completely depends on the requirements. I do not believe there is a uniquely better e-signature solution for all scenarios. For example, if the type of documents to be signed require low to medium reliability only, most modern e-signature platforms could be ok, subject to meeting legal requirements in the applicable jurisdiction, but if the document must meet stringent regulatory and statutory requirements that include high reliability of identity of signers, those platforms do not typically meet that threshold.Ideally, you would analyze, define and obtain agreement as to what constitutes the minimal acceptable legal reliability threshold you are willing to accept - or that readers of that document will accept. Next, define the technology requirements that correspond to that threshold. Finally, research e-signature options that meet these requirements and provide the best combination of price, features, scalability, etc..Finally, it should be noted that higher legal reliability e-signature platforms and solutions can always accommodate lower reliability documents while the converse is not true…

-

As a defense attorney, how would you handle having to “break” someone on the witness stand that you may believe is a victim of y

Shades of Nero Wolfe! I am not and never have been a criminal defense attorney, but in my articles I have occasionally been assigned issues of criminal law or procedure, so have isolated bits of knowledge. I do believe, however, that criminal defense lawyers are in the front lines of those who defend democracy since their constant job is to see that every defendant receives a fair trial before an impartial adjudicator and that the result is supported by the trial evidence properly admitted. Plus they seem to always have the best stories.I once did have a witness, not mine, who more or less “broke” during a trial. This was a state court matter. My client owned a business selling cell phones and leasing service for them. The future defendant came in and purchased a cell phone and service, and for some reason signed the related documents over the course of two days instead of all at once. I don’t remember why and it didn’t matter to the trial. He paid the phone fee on the second day, but refused to pay for service over the course of nearly three months. His reason for not paying, he said, was that he was “testing” the service. My client had records of the numbers he called and the length of time for each call. I had taken his deposition, and he had admitted he signed each document I showed him concerning the purchase. The only real issue was whether his claim of testing the phone service was going to stand up.For our trial judge, we drew an older man who probably presided at God’s case against Cain, but was one of my favorites because he was experienced, didn’t like having his time wasted but would listen politely, and knew contract law. It was an excellent draw for us since I wouldn’t have to spend time explaining how contracts worked.The defendant showed up for trial with another fellow he introduced as his cousin and said he had been with him on the second day when he signed the rest of the documents and picked up his phone. I assumed the cousin was there to try to bolster the defendant’s claim of testing. But if they hadn’t already discussed the case, I was going to deny them the opportunity to coordinate further, so I invoked the “Rule” at the start, meaning the exclusionary rule that said anyone not a party had to wait outside in the hall until called.I started with the defendant. I put him on the stand and we began the basic stuff - the contract and its terms. I asked him the same stuff I had in the defendant’s deposition - “do you recognize this exhibit? what is it? is that your signature on page #?” Usually these are pretty routine, but the defense hadn’t wanted to stipulate admissibility, so I was just laying the groundwork. Needless to say, there was nothing in the documents about a period for testing, but there were warranties. So I am just loping along doing something I had done lots of times before and then …For some reason never made clear, the defendant decided to deny he had signed the second day’s paperwork. This really was the less important stuff, but it had warranty language in it, so one would think he would want it in. I suspect he just lost track or panicked. I am standing there with the transcript of his deposition in plain sight in front of me. It even had little paper tabs in it. I was careful not to react in any way to his denials - just a bit about being sure he looked in the right place and knew he’d seen them before. I took him through the rest of the paperwork and he insisted he hadn’t signed anything on day 2. No one seemed to catch it except my client. But what I did next got the judge’s attention because it was unusual.I asked the judge if I could suspend the defendant’s testimony for a bit, subject to recalling him later, while I called another witness out of order to “clarify” a point. Still no penny dropped with the defendant or, as far as I could tell, with his attorney, although I noticed the trial judge changed his posture so I figured he knew something was up and it had to do with the signatures. The judge let me call the cousin in from the hall, and now looked alert, waiting to see what was going on.The defendant went back to his seat beside his attorney and there was a lot of whispering until the judge shushed them. I called the cousin in from the hall, telling him only that we were going to be there for a while yet, and were taking him early so he wouldn’t have to stand around in the hall any longer than necessary. Now he is not my witness, so I designated him as hostile before I called him in so I could lead him some, but there really wasn’t much need.He obligingly recognized his cousin’s signatures on all of the documents, even correcting me when he thought I missed one, and explaining that he was present when the paperwork was all signed. He was pleasant, cheerful, and completely oblivious to the implications, so I knew they hadn’t discussed denying the signature beforehand - plus I still had the deposition statements to whack the defendant with if necessary. But it wasn’t.After the cousin finished and was excused, subject to later recall by the other side, the judge invited counsel up to the bench. And here is where experience mattered. The judge caught on that I wouldn’t have done what I did if the defendant hadn’t lied about signing some of the documents.I don’t use profanity, so I will use *** instead. The judge was annoyed by the defendant’s obvious lies. In whispers, the judge asked me if I had any further evidence regarding the question of the defendant’s signatures on the documents we’d been discussing and this was when the defendant’s lawyer woke up. He tried to object to the question, but the judge burnt him with a look that was better than a ruling. I just said I had a transcript of his deposition during which his memory was different, and that was all I said. The judge gestured to the defendant’s lawyer to come a bit closer (he’d backed up some during the burning) to the bench and the judge said words to the effect that his “G**D*** client had better settle with me before he was judicially determined to be a ***** perjurer and maybe recommended for prosecution for wasting the court’s time on a ****show like this case, and he was giving us a recess to resolve it without his [the judge] having to listen to any more **** from the *********** defendant.So we went outside, the defendant’s attorney “conferred” with his client, and we did just what the judge ordered. I never did find out why the defendant thought three months of free testing was appropriate.

-

What made David Bowie’s music unique?

It is all very listenable, appealing, and virtually, all his early albums, through 1967 to 1983, are all good songs. Every album, is playable, through. Most of the time. This rarely happens with all other musicians. Or, you skip, or contemplate, only certain songs. Bowie, typically, transformed the process, to make almost every song, count. Credible. He produced, a massive body of work, in those years, and following. Few artists can compare, in terms, productivity, longevity, and still remain as good, or even better, after a decade and more. Yet, he remained, much longer in the music industry, always maintaining his status. Bowie, though, was truly very adaptable, always able to reinvent himself, or search for instant new ideas, or conjure up basically, anything, out of the blue. Yet, naturally, he also took a lot of inspiration, influence, not just in his formative years. Yet, still remained highly individualistic, and almost incomparable, since no-one quite had his sound, music-theory, and in turn, a greater influence on everyone else, or music, culture, in general:[/] Bowie “See Emily Play” (1973). From the album Pin Ups. All songs were based on covers/remakes. He chose an interesting selection, and transformed every song.[/] Pink Floyd “See Emily Play” (1967). Original track. ^^[/] ^^ 1973.[/] ^^ The Model Twiggy.[/] Bowie “Queen Bitch” (Live Old Grey Whistle Test 1972). This highlights, just how good he could be. Not to mention, foreshadowing punk, by many years. The song itself, is originally from his 1971 album, Hunky Dory.[/] Bowie “Rubber Band” (based on his 1966 single release, in mono). the song again appears on his 1967 debut album release, re-recorded in stereo. The video, is from 1969, which also featured segments of mime, among other songs, entitled “Love You Till Tuesday”. It served as a promotional video album.[/][/] Bowie “Space Oddity” (1969). Original version. This version, appears on his video album,from that year, yet only officially released in 1984.[/] His second solo album, released in 1969, featuring the official release, Space Oddity. So too the official single release.[/][/] ^^ 1969 single release.[/] ^^ 1972 reissue of the 1969 album. Entitled, Space Oddity, with the title track.[/] Bowie “Space Oddity” Official video, of the official 1969 version, taken from his second solo album. The video was produced December 1972. New York.[/] ^^ Early years. Between 1967 - 1975.[/][/] Bowie “The Width of a Circle” (recorded live, 1973, Motion Picture). The song here is some 14 mins long, extended version, with great guitar antics from Mick Ronson. Great backing band. The song was originally released on his 1970 album, The Man Who Sold The World.[/] ^^ Mick Ronson.[/] Bowie “Golden Years” (1976). The song was originally released as a single in Nov 1975. The album version, is slightly longer, by about half a minute.[/] Bowie “Moonage Daydream” (1972). Classic album.[/] Bowie “TVC 15” (1976). The song warms up, then basically, an amazing sound. Great production.[/][/][/] Bowie “Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps)” (1980).

-

How close did the US come to losing the Battle of Midway during WW2?

Pretty close. It was a near run thing.The Americans entered the Battle with good advantages. They had the element of surprise. They had broken the enemy codes and knew their plans even their Aleutian adventure. (And obviously the Japanese were unaware of this fact.) There were prepared! The Americans brought more aircraft/pilots than the Japanese - the Americans brought along the survivors from the Lexington and patched up the Yorktown. They had radar and could detect enemy aircraft 100 miles away; the Japanese did not. And they had a simple and effective plan - strike the enemy carriers when they were distracted with Midway Island’s defences.Yao Zhan's answer to What should Nagumo have done at the Battle of Midway when he received his first sighting report of US carriers?But the Americans were still inexperienced compared to the Japanese. The Hornet strike team went the wrong way. The US Marine divebomber pilots from Midway Island had insufficient air training. The American strike force went in uncoordinated and often piecemeal, one at a time, allowing the Japanese to swat each threat away without getting any damage.And. The Dauntless divebombers from Enterprise that helped to deal the devastating blow to the Japanese carrier fleet were initially lost. They couldn’t find the enemy fleet. They were low on fuel.Fortunately, the Enterprise dive bomber commander, Wade McClusky, spotted the Arashi, a lone Japanese Destroyer, in the ocean (he misidentified it as a cruiser in his report). Nagumo had ordered it to attack an American submarine. Once its job was done, it headed back to the fleet.McClusky put two and two together and deduced that the single warship was heading back to the fleet. So he took its direction.The word “luck” is not one coined by me. You can read it in the American battle account. This is the report of Wade McClusky’s, Commander of the Enterprise divebomber group:Arriving at the estimated point of contact the sea was empty. Not a …vessel was in sight. A hurried review of my navigation convinced me that I had not erred. What was wrong?With the clear visibility it was certain that we hadn't passed them unsighted. Allowing for their maximum advance of 25 knots, I was positive they couldn't be in my left semi-circle, that is, between my position and the island of Midway. Then they must be in the right semi-circle, had changed course easterly or westerly, or, most likely reversed course. To allow for a possible westerly change of course, I decided to fly west for 35 miles, then to turn north-west in the precise reverse of the original Japanese course. After making this decision, my next concern was just how far could we go. We had climbed, heavily loaded, to a high altitude. I knew the planes following were probably using more gas than I was. So, with another quick calculation, I decided to stay on course 315 degrees until (1000), then turn north-eastwardly before making a final decision to terminate the hunt and return to the Enterprise.Call it fate, luck or what you may, because at (0955) I spied a lone … cruiser scurrying under full power to the north-east. Concluding that she possibly was a liaison ship between the occupation forces and the striking force, I altered my Group's course to that of the cruiser. At (1005) that decision paid dividends.(Painting by RG Smith)Jackpot. At 1002, he radioed Admiral Spruance on the Enterprise to say:This is McClusky. Have sighted the enemy.At this stage, the Dauntless bombers who had a max range of 175 miles with their 1000lb bomb were low on fuel. Some of them had already crashed into the sea after running out of fuel. To compound the problem, some of the Yorktown bombers, including the one being flown by Max Leslie commander of the Yorktown dive bomber group had accidentally dropped their bombs into the sea due to a technical glitch.By chance, the strike team from the Yorktown, comprising of Wildcat fighter escort, Devastator torpedo bombers and Dauntless dive bombers, arrived around the same time as the Enterprise group. The Yorktown team was more experienced and better coordinated. However, Leslie’s divebombers, were not the first to sight the enemy carrier fleet. It was the Torpedo group led by Lt. Commander Lance Massey that did. Massey’s torpedo bombers VT-3, together with the six Wildcat fighter VF-3 plane escort led by Lt. Cmdr. Thach, did the job of drawing the enemy CAP down to sea level, forty two A6M2 Zero fighters !!!!!! flown by elite enemy pilots.(“Zero” A6M2 fighter - a sight that brought terror to the enemy in 1942)Massey and Thach’s groups distracted the forty two Zero fighters and enemy AA from the divebombers who were commencing their high altitude attack. For the first time, Thach used his famous aviation tactic, the “Thach Weave - Wikipedia”, to confound the deadly Japanese Zero fighter. It worked! Despite the incredible odds, he managed to shoot three Zeros down. And, he survived too, much to his own pleasant surprise.Lt. Cmdr. John Thach. Veteran of the Battle of Coral Sea and Midway. He survived the sinking of the Lexington and was posted to the Yorktown. After the battle, he was assigned to training schools to teach the next batch of fighter pilots.Massey made a small change of course to the right. We took off on a heading of about southwest, and I wondered why he did that. Looking ahead, I could see ships through the breaks in the clouds, and I figured that was it. … The six Yorktown Wildcats were the only fighters that got any combat over the Japanese fleet—no other fighters. And VF-3 was the only fighter squadron in the Battle of Midway that had any signNow aerial combat later in defense of our carriers. Lt.Cmdr. John Thach account.Lt Cmdr. Lance E. Massey’s commander of Torpedo Bomber group VT-3.Massey’s Torpedo Bomber VT-3 group were not so lucky. Out of the 12 Devastator torpedo bombers, only 2 survived. Massey and his crew were killed in battle.The successful combined strike by the Yorktown and Enterprise bombers owed a great deal to luck. The torpedo bombers went in while the Dauntless divebombers were still lost in the clouds according to Leslie’s report.Their commanders had lost communication at this crucial moment. Leslie said he would not have found the enemy fleet if he didn’t see the Massey’s torpedo group turn to that direction. This is an excerpt of his battle report.Meanwhile, the Dauntless divebombers from the Hornet could not find the enemy carrier too. Their Wildcat escorts - eleven plus crashed into the sea after running out of fuel. The bombers managed to land on Midway Island before they ran out of fuel. They totally failed to find and bomb the Japanese aircraft carriers.If the McClusky and Leslie had been incompetent, over cautious, or plain unlucky, or made an error like the Hornet group - that deadly strike at 1015 would never have happened.Up to that point, the battle was not going well for the Americans. They had lost numerous aircraft and had not damaged a single enemy aircraft carrier despite their best efforts. One US Maruader bomber did come close to killing Nagumo and his entire staff with a “kamikaze style” attack; it crashed into the sea, all its crew perished.The American torpedo bombers including the new Avenger bombers were massacred by the Japanese CAP.Captain Mitscher the commander of CV-8 Hornet carrier had sent his forces the wrong way. None of Hornet’s divebombers attacked the enemy carriers that morning.Cmdr Waldron, the leader of the ill-fated Hornet Devastator torpedo group, disobeyed orders and found the enemy carriers. He bravely lead his bombers despite having no fighter escort. They were the first among the carrier bombers to attack the Japanese carriers. They were all shot down, without inflicting damage. Only one man survived from Waldron’s flight, miraculously surviving an ordeal in the ocean. Only one aircraft from Torpedo 8, flown from Midway Is., made it back, badly damaged.*The Dauntless divebombers armed with their 1000lb bombs were also operating at their maximum range. Many of them including the one flown by Max Leslie - seen in the photo below - had to ditch in the sea due to lack of fuel. At the end of the day, this wasn’t a serious problem because the Americans had sunk all of the enemy carriers. But if their attack had failed, it would have meant the Americans carriers wouldn’t have enough aircraft to mount a strong counter attack.(Max Leslie’s Dauntless crashing into the sea after running out of fuel, after the successful strike in the morning.)If Nagumo had acted prudently and sailed away from the mysterious enemy fleet after he recovered his Midway Island strike force at 0917, it is also possible that the Enterprise and Yorktown divebombers, low on fuel, would not have found him. At the very least, it would have drawn them further away from their carriers, and placing greater chance of them running out of fuel and crashing into the sea.And of course Nagumo was now aware that there were American aircraft carriers in the vicinity. Previously, the Japanese were totally oblivious to the fact that the Americans had a fleet stationed off Midway Island. When they received news of this, they initially discounted it. They were also of course unaware that their codes had been broken and would remain oblivious to this serious problem until the post-war period.Yao Zhan's answer to How did the Americans win the Battle of Midway? Was it because of technological superiority or intelligence superiority?The dive bombers were the final throw of the dice for the US Navy. If the Enterprise and Yorktown dive bombers failed like their Hornet counterparts, the Americans would have faced a disaster. They had suffered serious aircraft losses. Their torpedo bombers were massacred. Hornet had lost most of its Wildcat fighter planes - leaving only six left. Many of the Enterprise and Yorktown divebombers would fail to return back to their carriers; Enterprise lost half of its dive bombers by midday.Meanwhile, the Japanese 2nd enemy invasion fleet was also approaching Midway Island. They would have been able to bombard its airstrip at night. And, if Nagumo kept his distance, he could have used the longer range of his aircraft to take out the enemy carriers with impunity.Once the element of surprise was lost, the Americans would have lost their most important asset. The Japanese now knew that there were enemy carriers in the area. What’s more, the Americans had suffered serious aircraft losses ; if this first strike failed, they were in dire danger.Chances are that the Japanese with their elite aircrew would have won the battle and sunk all the enemy carriers without serious losses themselves.Not belittling the efforts of the American cryptoanalysts, the Midway Island airforce, and the brave American Torpedo bomber crews and of course the skill of the Enterprise and Yorktown divebomber crews, but it was very lucky that the Enterprise and the Yorktown Dauntless divebombers showed up at the same time while the enemy Zero fighters had all come down to deal with the Devastator torpedo bombers and Thach’s six Wildcats.If you disagree, read the battle reports of McClusky and Leslie.The Dauntless divebomber attack run was conducted unopposed, ideal attack conditions. Had they arrived at the wrong time, the outcome could have been considerably different.Update: I don’t have my copy of Parshall and Tully’s Shattered Sword with me. So I haven’t checked the info on Yorktown.(There is some conflict in the reporting over the timing of the strike. I believe its because the Japanese were using Tokyo time zone, the Americans were using the local time zone.)Source and other reading material:Yao Zhan's answer to How could Japan win the Battle of Midway?Yao Zhan's answer to What should Nagumo have done at the Battle of Midway when he received his first sighting report of US carriers?*Mitscher and the Mystery of Midway“Jimmy” John S. Thach account: Flying into a Beehive: Fighting Three at MidwayMax Leslie’s Battle Report Battle of Midway. You can download it here: Battle of Midway Lt. Max Leslie Signature? - MILITARY AIRCRAFT & AVIATIONhttps://www.cafutahwing.org/batt...Jonathan Parshall and Anthony Tully, Shattered Sword. Shattered Sword is the latest in-depth examination of the actual battle. Shattered Sword is extremely well researched and worth reading many times over. (When I wrote my answer, I did not have my copy of the book with me and made a few errors which I have since corrected).Barrett Tillman, Osprey Series - SBD Dauntless Units of WW2 - if you want an easy to read book of the battle, Osprey has a series on the Battle. This is one of them. Has pictures too. :)Joseph Rochefort - WikipediaThe 'Codebreaker' Who Made Midway Victory PossibleThe First Team: Pacific Naval Air Combat from Pearl Harbor to Midway: John B. Lundstrom: 9781591144717: Amazon.com: Books John B. Lundstrom’s, The First Team: Pacific Naval Air Combat from Pearl Harbor to Midway (1984). Lundstrom analyses the aerial combat using Japanese and American sources to better understand and corroborate combat reports. His work is absolutely amazing and detailed. It is a must have for any person interested in the Pacific campaign and air combat.The Barrier and the Javelin: Japanese and Allied Strategies, February to June 1942: H. P. Willmott: 9781591149491: Amazon.com: BooksThe Barrier and the Javelin: Japanese and Allied Strategies, Feb to June 1942 by H.P. Willmott. This is a very satisfying book to read as it explores the dilemmas and possibilities facing the Allied and Japanese leaders leading up to the Battle of Midway. Did you know that Admiral King, the Chief of the US Navy asked the British for the use of two of their aircraft carriers, HMS Indomitable and Formidable prior to Midway but he misled them about USN losses and damage at the Battle of Coral Sea? So the British refused King’s request.Yao Zhan's answer to Could the battleship Yamato have turned the tide in the Battle of Midway?Yao Zhan's answer to What were the biggest tactical and strategic mistakes that the Japanese made during WWII?Yao Zhan's answer to Assuming Japan Navy won at battle of Midway, what could happened during the course of war?Yao Zhan's answer to During the first stages of the Battle of Midway, why did the Japanese not choose to use B5Ns or D3As for reconnaissance?Yao Zhan's answer to What are the best books about the Battle of Midway?Joseph J. Rochefort was an American Naval officer and cryptanalyst. His contributions and those of his team were crucial to the American victory in the Battle of Midway. Despite his contribution, Admiral King, the head of the USN, demoted him to command a dry-dock for the duration of the war. King’s staff were embarrassed because they did not believe the intel which as we know turned out to be correct. So they sent the brilliant cryptanalyst to waste his time on a dry dock. He received his well deserved medal posthumously long after he had died.Battle of Midway: 3-6 June 1942 Combat Narrative

-

How do I read music notes?

Music is read from left to right, where going right represents moving forward in time. Since music is not capable of time-travel, it always moves forward, which means to the right. Certain symbols can tell you to go back to an earlier section of music, though, and play it again — which I guess is more like looking through a scrapbook than actual time-travel. Discuss. The grid of five lines is called the staff. Notes can be snapped to any of the lines themselves, or to any of the the four spaces between them. The higher up on the staff a note is situated, the higher its pitch relative to the rest of the staff. The the lower the note is placed on the staff, the lower its pitch. We can also extend the pitch-range of a given staff upward or downward by adding 'temporary' lines, called leger lines, above or below the staff on a note-by-note basis. You can see this has been done to the first note in the example, and it happens once again at the end of the example. Already, then, you can discern the notation well enough to tell that in the above example there is a trend in which the pitch gets higher as the music moves forward in time. If you can do that, you can read music. The rest is just filling in details, no kidding, and you simply get better with practice. Musical notation is not cryptic or arcane. Like any constructed and evolved system it has its discrepancies and idiosyncrasies, but on the whole it is quite accessible and intuitive. In the beginning, there was rhythmRhythm is sometimes neglected in the early stages of standardized music education. Because students and their teachers are so intensely concerned with making sure that the student knows where all the notes are on the instrument and where all the pitches are on the staff, sometimes rather less attention is paid to being able to understand where the notes are in time. This leads to stunted musical growth in some cases, and tragically prevents the development of many otherwise perfectly serviceable would-be funk guitarists. It is extremely important to understand that standard musical notation is not designed to tell us exactly how long the sounds last. It is only designed to tell us how long they last in relation to one another.The rhythmic values of notes, their lengths relative to one another, are in the German and American systems of nomenclature expressed as fractional relationships. Thus we have quarter notes and rests, half notes and rests, sixteenth notes and rests, and so forth. The British may have the upper hand on America in their use of the neat and logical metric system of measurements (which, you should remind them at every opportunity, they only appropriated from the French), but they must admit that they most backwardly continue the use of bizarre and uninformative names like minim, crotchet, and hemidemisemiquaver to describe these fractional relations in time-value. Though it is not at all intuitive that a semiquaver lasts one quarter the length of a crotchet, it is quite intuitive that a sixteenth note should last one-quarter the length of a quarter note: since 1/16 is 1/4 of 1/4, it takes four sixteenth notes to fill the same length of time that one quarter note fills. The Tree of Life or Holy Totem of Rhythmic Notation, then, looks something like this:one whole equals two halvesone half equals two quartersone quarter equals two eighthsone eighth equals two sixteenthsone sixteenth equals two thirtysecondsFrom this it follows that, say, four eighths equal a half, and eight eighths equal a whole. We are doing nothing more than expressing the division of time-lengths according to very basic fractional proportions which are often reducible at will to even simpler fractions. If you're brand new to reading rhythms, you may need to enlarge this diagram and study it closely — it may not 'hit you' all at once. And that's okay, as I'm sure there are still British people reading this who do not yet understand why crotchet is a very dumb name for a simple quarter note.The fraction at the left of the diagram, 4/4 (uttered as four four, not four fourths or four over four), is the time signature. In this case it tells us that there are four quarter notes, or the equivalent in duration of four quarter notes, in each measure. That is all it says. Do not let anyone (especially not anyone British) tell you that it means, "There are four quarter notes in a measure, and the quarter note gets one beat." Nothing in the time signature says the first thing about beats or who gets any of them. The top number says how many: four. No sooner than you have asked, "Four what?" the bottom number informs you: four, meaning one-fourth, representing the quarter note. So in this time signature there are four quarter notes or the equivalent in each measure. The measures, also known as bars, happen between the bar lines. Those are the vertical lines which cut through and segment the staff every so often (every four quarter notes, to be exact, in this case). Bar lines are visual references only, and have no time-value; they are not stop signs, or even yield signs.Notice that there are no quarter notes in the first measure, only one whole, and its equivalent, two halves. These two things — the whole note on top, and then the pair of half notes below — are occurring at the same time, and they occupy the same amount of time relative to one another since 1/2 x 2 = 1 (since two halves equal one whole). Since one whole also equals four quarters, hopefully you can see how the time signature works in establishing the length of a measure: though there are no quarters in the first measure, that measure still contains the equivalent of four quarters, as does every other measure pictured.Each one of these measures, then, occupies the same amount of time relative to every other measure. Though the number of notes is increasing in each measure as we move forward in time to the right, we are really just cramming more notes into the same amount of space with each passing measure: the measures are not getting longer, they are just getting busier. Those sixteen very busy-looking sixteenth notes at far right take exactly the same amount of time to go by in total as the lonesome single whole note at the beginning. You will note (terrible pun intended and in fact celebrated) that:the whole note is hollow, and has no stemthe half note is hollow, but does have a stem poking outthe quarter note is filled-in, but has no beams/flagsthe eighth note is filled-in, and has one beam/flagthe sixteenth note is filled-in, and has two beams/flagsThis is how we tell the notes apart. As the values keep getting halved going smaller in length from the sixteenth (thirty-second, sixty-fourth, etc.), we simply add one more flag each time. It takes some practice to become fluent at recognizing these values by their appearance on the page, just as it takes us time as children to learn our letters, but already you should grasp the underlying principles if I have done a half-decent job of explaining the whole thing. Sigh. A note represents a sound happening. For each of these note-values, there is a corresponding symbol called a rest. A rest is a place-holder which tells us that no sound is happening during that span of time:Each rest has a unique look, just as each kind of note does. You can see that the half rest is the whole rest turned upside-down, the quarter rest is sort of its own animal (like a crotchety Englishman, really), and the sixteenth rest is like the eighth rest only with two little doodads on it instead of one.Learning to recognize all of these different beasts quickly by sight just takes repetitious practice — it doesn't require any insightful knowledge. To see if you are grasping the basic concept of fractional/proportional rhythm and the time signature, try answering the following questions:Do six quarter notes take up more or less time than four half notes?How many eighth notes could we fit into one measure of 3/4 time?How many sixteenth notes could we fit into one measure of 6/8 time?If an incomplete bar of 4/4 time contains two eighth notes and a half rest, what one note or rest could we add that would rhythmically fill up and complete the measure? (the answers are at the bottom of this post, but don't tell anyone that.)We have not yet mentioned dotted notes. The rhythmic dot is a diabolical symbol we place just to the right of any note or rest to add half of its rhythmic value onto itself, that is, to make the dotted version 150% of the length of the un-dotted version. This means that since a quarter note is two eighth notes in length, a dotted quarter note is three eighth notes in length; since an eighth rest is two sixteenth rests in length, a dotted eighth rest is three sixteenths in length. Probably we should also mention ties. These are not the same as neckties, which I never wear if I can get away with it, since I enjoy breathing. A tie is a curved line or ligature which can join two notes together. In doing so, it combines their lengths into one sound. Therefore, the following two measures of music sound exactly the same:In the first measure there are two sounds, represented by two notes: one sound is represented by the half note and the other by the quarter. Though there are three quarter notes in the second measure, still there are only two sounds, since the first two quarters are tied together, making them sound just the same as one half note. It might not be immediately apparent why ties are needed at all; one common reason is for allowing a single sound to extend across a bar line, by tying together the notes just to either side of it.You can tie as many notes together in sequence as you wish. When an opera singer holds a high note so long that you begin to squirm in your seat, there is a pretty good chance that ties are involved somehow. Tempo, and "keeping the beat"If you are not yet dizzy and disoriented, you may be wondering how it is that musicians know how long these sounds are supposed to actually last, if the rhythmic values of the notes and rests, all these quarters and wholes and dots and ties, only describe fractional relations and not duration in terms of seconds or minutes or visits to the Department of Motor Vehicles.This is the question of tempo. If you visit Italy you'll be surprised to learn that this word can also refer to the weather, but for our purposes it means the speed of the music. We typically define tempo in terms of a steady pulse. That steady pulse can be assigned to any note value we choose. Try patting your right leg with your right hand roughly once per second, and keep that process going for a bit. It's not as important that you tick precise seconds as it is that the pulse be even and unchanging. Let's arbitrarily assign this pulse to the quarter note (in much of written music, the quarter note does get assigned the pulse, but it is by no means a rule). You are effect tapping a string of quarter notes, which looks like this:Now, while continuing to tap once per second on your right leg, take your left hand and tap your left leg twice per second, dividing each second into two even parts. For every one tap on your right leg, you will make two taps on your left leg, which also means that every other tap on the left should line up with a tap on the right. If this presents a coordination problem, you may be British. But you'll get it with a little persistence. Since a quarter note is as long as two eighth notes, you are now tapping eighth notes on the left leg while you tap quarter notes on the right leg:Try starting the process over from scratch, beginning with quarters on the right leg again and then adding equal eights, two per quarter, on the left leg — only this time, make the quarter notes go by rather faster. This means the eighth notes on the other leg will also go by faster, since they must maintain their proportion to the quarters, two to each. This is the concept of tempo applied to rhythmic notation. Feel free to let your fancy wander by speeding up and slowing down at will, but remember always to keep two eighths to each quarter.The tempo can change, and indeed any note value can be assigned to the basic pulse — quarter, eighth, whole, whatever — but the proportions of the note values, their fractional relationships to one another, do not change.We indicate general ideas about tempo using words, often dusty but beautiful old Italian words like Allegro (pretty lively), Adagio (quite slow), Presto (very fast), and so forth. We can also use a more scientific measurement called beats per minute (BPM), which is what a metronome madly ticks away at. Since we can assign the beat/pulse to any note value we want, metronome markings are generally given as "quarter note = 120 BPM," or "half note = 72 BPM," and these values are checked against the ticking of a metronome to give us the precise tempo we need. I have noticed that a common trope in dime-store theory books is to assign Italian tempo terms to ranges of BPM. Allegro might be given as 100 - 126 BPM, Andante as 72 - 88 BPM, and so on. You should know that this has no basis in reality, as these terms were invented and were in common use long before metronomes and BPM existed, and that those who claim that tempo terminology can be even approximately quantified in terms of BPM to any useful extent have been grossly misinformed. Humor me with two more brief rhythmic experiments. Define the speed of your quarter note as about once per second, as we did before (that's quarter note = 60 BMP in metronome-speak), and get it going for a bit on the right leg again, just to get your bearings. Now look at the following example:You can see that each measure of 4/4 time contains a quarter note followed by a quarter rest, twice over. Can you now 'play' this example by tapping it on your leg? Remember that the notes and rests are exactly the same length here relative to one another and to the pulse you have established — they are all quarters — and that we don't stop when we come to a bar line; bar lines are for visual reference only. If you have difficulty doing this at first, or aren't sure if you are right, try counting '1, 2, 3, 4' evenly, with each numeral representing a quarter note — just as if you are counting seconds. You should tap on 1 and 3, since that's where the notes are in each bar, and make no sound on 2 and 4, since that's where the rests are in each. Easy enough? You are now officially reading music, or at least its rhythmic aspect. Try reversing the pattern so that you rest on 1 and 3 but tap on 2 and 4 — swapping out the notes and rests — and imagine how that might look written down. For our second experiment, see if you can tap out the following:Don't fret over the new time signature (3/4). In fact, ignore it totally for the moment. Just concentrate on first establishing your quarter note pulse, and on remembering that two eighths must fit evenly into the same amount of time occupied by a quarter, relatively speaking. If we were to count this excerpt aloud, we might say:1 2 & 3 | 1 & 2 & 3You may find this slightly more difficult to do than our earlier efforts, because switching from quarters to eighths requires you to temporarily 'let go' of physically marking the pulse. In order to "keep the beat," you have to maintain an imaginary stream of even quarters in your head, just as if you were still marking them with one hand on one leg as we did at first. It is even better if you can maintain an imaginary stream of eighths in your head instead (1 & 2 & 3 & | 1 & 2 & 3 &), because this subdivision will help you internally mark the pulse with greater accuracy.This takes practice to master, particularly when the rhythms get more complicated than these. But you can do it, and you should try to master the idea very early on, because it is the heart of musicianship. PitchWe have said an awful lot about rhythm so far, because it is extremely important. But we of course also need to know how to read pitch, which tells us how high or low a note is. As we mentioned earlier, the higher the note is on the staff, the higher in pitch it is relative to the other pitches on the staff. But how do we know which pitch is A, and which is F, and which is R — wait, there is no R, as the pitches are only lettered A through G; perhaps the British have an R — how do we determine exact pitch just by looking at those lines and spaces? The answer is that the five lines and four spaces of the staff tell us nothing about pitch-letters until we place a clef on the staff. Clef is French for key, and while clefs do not at all determine 'key' in the musical sense, they are necessary for us to be able to name the pitches on the staff. The treble clef produces a series of pitches which looks like this:The first C, which is the first pitch given here, is known as middle C. The next C is pitched an octave above middle C, and the other C to the right is pitched two octaves higher than middle C. You can see that we name the pitches by counting A through G and starting over again, and that moving from one 'slot' to the next — from a space to the next line, or from a line to the next space — also moves us the distance of one letter name; none are 'skipped' when we advance one slot at a time in either direction. Try following this gamut of pitches slowly forward through time, one at a time, reciting the appropriate letter name as you come to each note. Then go backwards, that is, leftwards, and do the same thing. (Congratulations — you just broke the laws of music by time-traveling. Never do that again.)Notice that the notes can sit well below or above the staff if we temporarily extend the pattern of lines and spaces using leger lines. The bass clef produces a series which looks like this (this time we'll start at the top and descend as we move forward in time; you'll see why soon enough): Here is another crucial concept: in this example, we begin with middle C, the same pitch we began with in the treble clef, and then go down in pitch from there. That is, the first pitch in this example is exactly the same pitch, represented by the same key on the piano, for instance, as the first pitch in the previous example. This is how the treble and bass clefs are different, and yet linked. Look at the second C in this bass clef example, an octave below middle C, and imagine trying to represent that pitch using the treble clef. You'd have to draw many leger lines below the treble staff and then laboriously count them all to figure out what pitch is being represented. This is why we use different clefs (and there are others still, besides just treble and bass): because it makes the pitches on the staff easier to read depending on where we are in pitch-land at a given time. Some instruments, and all the voices, read music from a single staff and may change clefs mid-stream as needed. Still others — like the piano or the harp, which can play a very wide range of pitches — read music from two staves linked together by a bracket into a grand staff, most usually with one staff using the treble clef and the other the bass. That quite imposing structure looks and works like this:The area within the box represents the zone in which the two staves 'meet' and share exact pitches in common. Middle C is underlined as it is represented by each of the two clefs, and the D and E that follow are also pictured redundantly as they are represented by each clef. So, the C, D, and E that you see in the bass clef within the box are exactly the same pitches as the C, D, and E you see written in the treble clef within the box.As you may know, we can apply accidentals — sharps, flats, naturals, and some other even hairier critters — to these pitches in order to slightly alter them: C-sharp, E-flat, A-natural, and so forth. A sharp raises the pitch by the interval of one half-step, a flat lowers the pitch by one half-step, and a natural is most often used to cancel a sharp or flat that has just occurred somewhere earlier in the measure, so that A-sharp can be made just plain old A again, for example. Since sharps and flats require a basic understand of pitch-intervals, which is another topic entirely, I think this is a good place to stop our basic introduction to reading musical notation.This little primer is by no means comprehensive — it is not intended to be — but this should be enough of an info-dump to get you started. My hope is that you can see that the language of musical notation is actually rather simple in character, far more simple than written language, really. If it doesn't yet seem simple to you, have no fear — it takes persistent practice and study to get fluent at reading music, as with any language, but as you continue to gain fluency you will begin to see the simplicity and elegance underneath the all the symbols and their relationships to each other if you do not see it already. Remember: right = forward in time; up = higher pitch; down = lower pitch. Everything else is simply elaboration on these key bearings. Honestly, the most difficult part of reading musical notation lies in the ability to extemporaneously apply your knowledge of notation to the physical aspect of playing an instrument. That is, your understanding of musical notation isn't terribly much good until it is applied to actual music-making, which is a mental-physical behemoth all its own. When I first began reading music as a child comfortably accustomed to doing everything by ear, it was a tremendous struggle to get started. Now, about thirty years later, I can read even fairly complicated musical notation almost without conscious thought, with as little effort or less as I use to read the written word, and can hear in my mind with high accuracy the sounds represented on the page just as you can hear these words in your mind. It's just that it takes a very long time, and a lot of regular effort, to get to that point, and even now I'm not as fluent at it as I could potentially be! (And I can still play quite well by ear and can jam down at the bowling alley with the best of them. The 'wisdom' that reading music somehow harms your musicality is a nonsense notion invented by people who never bothered to learn notation very well.)Do take heart, as there are many British people who can read music. That means that you can, too. N.B.: I actually love Britain and its people, and have been there before without being arrested. Here are the answers to the rhythm questions that were asked in the section on note-values:Less time, since four halves = eight quarters, which is more than six.Six eighths could fit, since 3/4 holds the equivalent of three quarters, and one quarter is as long as two eighths, and 3 x 2 = 6.Twelve sixteenths could fit, since 6/8 implies the equivalent of six eighths, and there are two sixteenths in an eighth, and 6 x 2 = 12.A quarter. The bar of 4/4 allows for the equivalent of four quarters. The two eighth notes add up to one quarter, the half rest takes up the space of two quarters, and this adds up to the length of three quarters, leaving room for one more.J. S. Bach: from the manuscript to the Johannespassion. Just a bunch of very handsomely placed half, quarter, eighth, and sixteenth notes and rests.

Trusted esignature solution— what our customers are saying

Get legally-binding signatures now!

Frequently asked questions

How do i add an electronic signature to a word document?

What is an eSign message?

How do i add an electronic signature ro web page?

Get more for Draw eSignature Word Later

- How To eSign Colorado Freelance Contract

- eSign Ohio Mortgage Quote Request Mobile

- eSign Utah Mortgage Quote Request Online

- eSign Wisconsin Mortgage Quote Request Online

- eSign Hawaii Temporary Employment Contract Template Later

- eSign Georgia Recruitment Proposal Template Free

- Can I eSign Virginia Recruitment Proposal Template

- How To eSign Texas Temporary Employment Contract Template

Find out other Draw eSignature Word Later

- Ssa 1695 form

- Bsnl landline surrender letter format in word

- Fillable broker of record form 41820384

- Ubs bank transfer document form

- Wv medicaid prior authorization form for imaging

- Dd2842 form

- Capital care medical group child patient registration form

- Boston paintball waiver form

- Graphing lab answer key form

- California 3 digit zip code map form

- The invention of hugo cabret full book pdf form

- Pacificsource corrected claim form

- Check list for bill processing goods services both form

- 1083 form

- Ds5505 form

- Gr 68069 form

- Crime scene entry exit log form

- Scsurplus form

- Brnc form pdf

- Gunblood unblocked 429366689 form